The permanence paradox: why shareholder value always wins

The powerful ‘Big Three’ index funds managers will not protect their portfolio companies from hedge fund activists, writes Jerry Davis

This article is republished with permission from I by IMD, the knowledge platform of IMD Business School. You may access the original article here.

The years since the 2008 financial crisis have seen two paradoxical trends in the American stock market. On the one hand, index fund managers BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street have rapidly grown to become the largest shareholders in corporate America, collectively owning roughly 22 per cent of the S&P 500. These “permanent universal owners“ could be a potent force for enabling corporations to take a long-term perspective, investing in their workers, aggressively reducing their carbon emissions, and building enterprises to last.

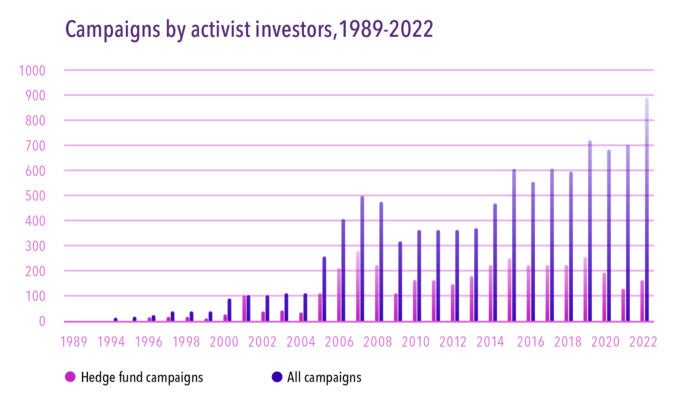

Yet the mid-2000s also saw a spike in hedge fund activism aimed at maximising share price immediately. Activism leapt just in time for the 2008 financial crisis and has not ebbed since, reaching such stalwarts as Coca-Cola and Procter & Gamble. In any given year, 200 companies face a hedge fund demanding cost-cutting, increased dividends, board representation, or often major asset sales or restructuring – particularly those companies that distinguish themselves by being too oriented toward stakeholders.

Which of these forces has had the biggest impact? This battle is not over, but for now, it seems clear that shareholder primacy is not likely to be replaced by stakeholder capitalism anytime soon.

Read more: Short selling Adani: how Hindenburg Research triggered the price plunge

The rise of index funds

In 1981, the US Internal Revenue Service issued a ruling clarifying the tax treatment of the 401(k) plan that allowed employees to direct some of their pay into mutual funds and other investments for retirement. These “defined contribution” retirement plans quickly spread across employers, and within a few years much of the American population found itself invested in funds run by Fidelity, Vanguard, and Capital Group. The industry’s assets under management increased 200-fold from $132 billion in 1980 to $27 trillion in 2021.

Fidelity, the biggest mutual fund family, focused on actively managed vehicles advised by internal experts, and by 1995 its ballooning assets made it the largest single shareholder in roughly 400 US corporations. Fidelity often found itself owning stakes of 10 per cent or more among competitors in the same industry. Vanguard, in contrast, focused on highly diversified indices such as S&P 500 and rarely accumulated a significant stake in a single company. Meanwhile, in 1993 State Street Global Advisors launched its SPDR, the first exchange-traded fund (ETF) that also tracked the S&P 500. Unlike traditional mutual funds, ETFs trade on a stock market just like a share in a company. The ETF model became wildly popular, and the predecessor of iShares launched in 1996, spawning dozens of ETFs. By 2003 iShares’ parent Barclays was the second-largest blockholder on the US market behind Fidelity, and in 2009 Barclays sold the iShares business to BlackRock.

The 2008 financial crisis was followed by a mass exodus of investors from actively managed funds such as Fidelity into “passive” index funds such as those overseen by BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street (the Big Three). For corporations listed in the most popular index – the S&P 500 – the results have been dramatic. In 2007, the Big Three owned seven per cent of the average S&P 500 corporation. Today they own 22 per cent, and in some cases more than one-third. If trends continue, we might see three financial institutions owning an outright majority of the shares of hundreds of US corporations.

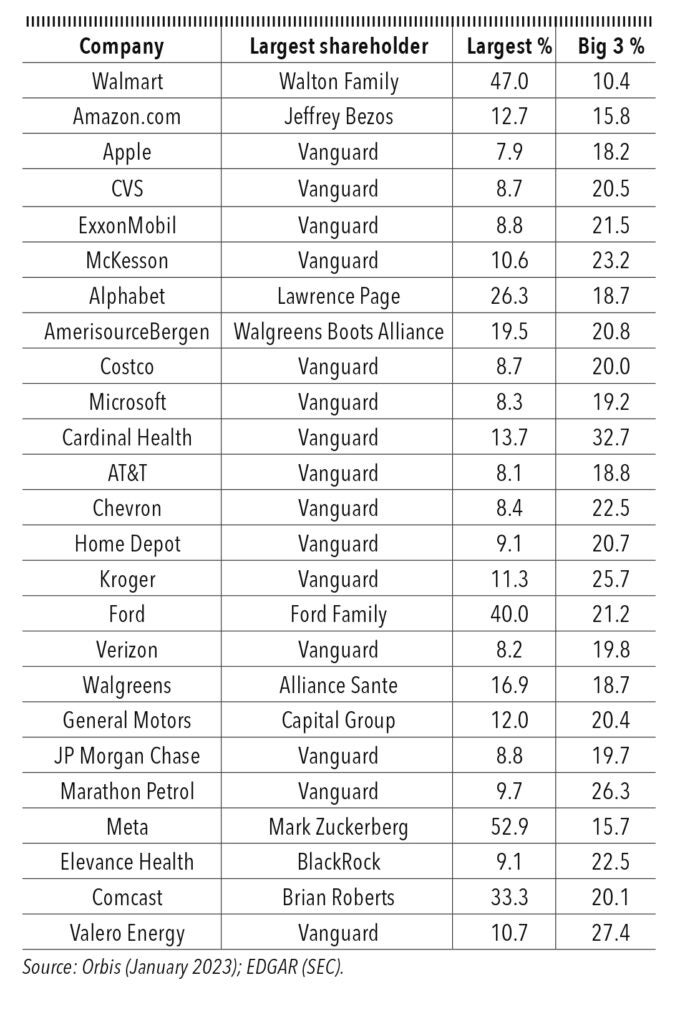

To make this concrete, the table above lists the largest shareholder for each of the 25 largest US corporations by revenues, according to data from Orbis and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). For 15 companies, Vanguard is the single largest shareholder, often including competitors in the same industry (e.g., Apple and Microsoft; AT&T and Verizon; ExxonMobil, Chevron, Marathon, and Valero). Among the largest 1,000 American corporations, Vanguard is the largest shareholder in 351.

This is something new. For nearly a century, American corporations have been known for their highly dispersed share ownership and the resulting separation of ownership and control. By 1930 nearly half of America’s 200 biggest corporations lacked a single significant shareholder, according to Berle and Means’ famous book. Today, not only do all major corporations have significant shareholders – they often have the same one.

Read more: Australia’s coronavirus bill: who is the government in debt to?

A force for collusion, wokeness, or something else?

Now, imagine that you are the single largest shareholder of hundreds of corporations in an economy. You have no discretion over which companies you buy and sell because you follow a set of rules that compel you to own a particular set of companies forever (or until your investors abandon you). You are, in short, a universal, permanent investor: universal because you own bits of every significant listed company; permanent because you never sell, regardless of performance. How do you use your power?

One possibility might be to encourage your portfolio companies to ease up a bit on their rivalries. Fierce competition and price wars might be great for consumers, but not so much for investors, who prefer steady profits. This was, of course, the rationale for the Standard Oil Trust and many collusive schemes since.

A second possibility is that index funds could somehow join together to force corporate America to adopt a “woke” agenda that is contrary to the nation’s perceived basic values and the funds’ own fiduciary obligations. This whimsical idea has gathered a surprising constituency among several Republican politicians as well as libertarian-minded Silicon Valley types as part of a broader backlash against ESG. Texas and Florida have both pulled billions in investments from BlackRock under the pretext that the asset manager is somehow boycotting fossil fuel companies. (To be clear, BlackRock’s holdings in fossil fuels are gargantuan.)

Are giant index funds woke? Critics on the left certainly don’t think so, as they point out that the Big Three are almost inevitably among the largest investors in every major fossil company, and fairly meek when it comes to climate activism. (Note that Vanguard holds the top spot in all the biggest US oil companies.) Larry Fink’s annual letter to CEOs urging them to think about the future is hardly a forced ESG re-education camp.

There was one major exception to the funds’ quietism, however: in 2021 climate activist fund Engine #1 ran four dissident candidates for the ExxonMobil board, and after making their case to the Big Three as well as other major investors, three of their candidates won. Perhaps this hit a bit too close to home for corporate America and its political allies.

And this hints at a third, more interesting possibility for index funds: that as universal permanent investors, they could become a force for long-termism, insulating companies from Wall Street’s pressures to focus slavishly on immediate profits. Imagine that companies are faced with a choice about whether to invest in their employees, which is costly in the short run but beneficial in the long run. As eternal investors, the Big Three might vow to support such investments even if a company’s share price might take a hit for now. Over time, as more investment flowed into index funds, a new ownership regime would usher in a golden age of patient capital. Indeed, a similar idea underlies the enthusiasm for “social wealth funds“ in which corporate ownership shifts over time into vehicles managed on behalf of society’s stakeholders. This theme was front and center in Larry Fink’s famous 2015 letter to the CEOs of the S&P 500.

The rise of activist hedge funds

As index funds have become the biggest shareholders in corporate America, activist hedge funds have created a counterforce, emphasising today’s profits. The graph shows the number of annual activist campaigns by hedge funds and by investors overall, according to FactSet. Hedge fund activism spiked in 2006-2007, and since 2010 it has averaged 200 campaigns per year.

What do hedge funds want? In short, higher share prices. Activist hedge funds are essentially beat cops enforcing shareholder primacy – and if anything, this comes at the expense of ESG.

Recent academic studies put a finer point on this, finding that activist funds explicitly target companies that have higher CSR ratings.

What do these campaigns look like? Salesforce occupies the tallest building in San Francisco and operates a phenomenally successful software business. Its biggest shareholders included Vanguard (7.9 per cent), BlackRock (6.9 per cent), Fidelity (4.9 per cent), T. Rowe Price (4.7 per cent), State Street (4.5 per cent), and its CEO (3 per cent). This is a strong bench of long-term investors collectively holding nearly 30 per cent of its shares. But in October 2022, activist investor Starboard Value announced that it had taken a position in Salesforce, and the following January Elliott Management made a multibillion-dollar investment. Both were expected to focus on cost-cutting (Salesforce had recently cut 10 per cent of its workforce), replacing board members, and restructuring, including potentially selling off Slack and Tableau.

In short, long-term shareholders are no insulation from activist hedge funds. The rise of index funds appears fully consistent with the existence of short-term pressures for shareholder value.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

What comes next?

Corporate ownership has undergone two major trends since the financial crisis of 2008. Index funds are inexorably absorbing the shares of America’s most prominent corporations. It is not hard to imagine a time in the coming years when an absolute majority of outstanding shares are held by three permanent universal owners. This could be an opportunity to re-tool the American economy toward a more long-term orientation.

At the same time, activist investors have become an inescapable force for prioritizing shareholder value above all else, and any company that fails at this demand – no matter what its size or ownership – is likely to feel the wrath of hedge funds demanding a board seat, cost cutting, layoffs, and restructuring. How these two tendencies will be reconciled is anybody’s guess. But prior American history suggests that shareholder primacy always wins in the end.

Jerry Davis is the Gilbert and Ruth Whitaker Professor of Business Administration and Professor of Sociology at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. He has published widely in management, sociology, and finance. His latest book is Taming Corporate Power in the 21st Century (Cambridge University Press, 2022), part of Cambridge Elements Series on Reinventing Capitalism.