Five economic policy priorities for Australia’s next government

As Australia heads toward its next election, key economic policy reforms will be crucial to financial stability, productivity growth, and global trade competitiveness

Australia’s economy faces mounting challenges, from cost of living pressures to global trade uncertainties. With the federal election approaching, economic policy will be central to shaping the nation’s future. The next Australian government must address productivity growth, interest rates, and fiscal pressures while driving economic growth and progress towards a net zero economy. Reforms should boost business investment, strengthen supply chains, and expand clean energy, critical minerals, and renewable energy sectors.

Managing population growth, an ageing population, and aged care are essential to maintaining living standards, while competition policy, labour market initiatives, and tax incentives can lift disposable income and GDP. With the Treasury, the Reserve Bank of Australia, and the private sector involved, ensuring longer-term stability and economic prosperity will be vital for the Commonwealth. As Parliament navigates United States–China trade relations and reassesses immigration, its response will shape Australia’s future.

A new report published by the e61 Institute and UNSW Sydney highlights the key areas that require urgent attention. It specifically focuses on a new global order, population growth, productivity growth, restoring fiscal sustainability, and addressing intergenerational inequity. The government must also address economic growth, business investment, and climate change policies.

How geopolitics impact Australia’s economic policy

Speaking at a recent e61 Institute and UNSW Sydney policy research partnership event, e61 CEO Michael Brennan provided a sobering assessment of Australia’s economic trajectory, warning of significant challenges ahead. “It is the conceit of every generation to believe that we live in some sort of unprecedented time, that the pace of change has never been so rapid,” said Mr Brennan.

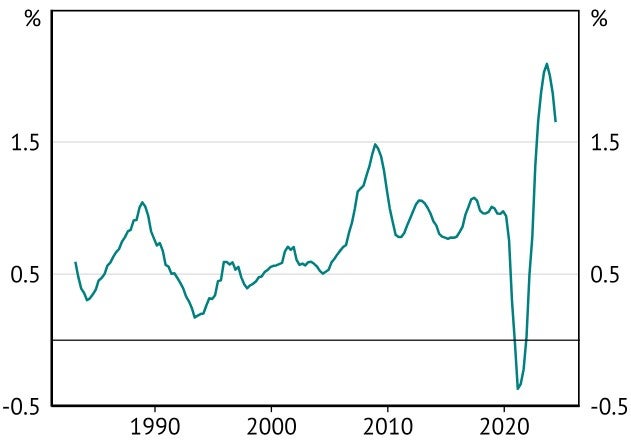

“And to be truthful, in purely technological terms, that’s probably false. If we look at the productivity growth statistics, the rate of economic change is, if anything, slow compared to much of the last 150 years.”

Photo gallery: e61 Institute and UNSW Business School policy research partnership launch

However, while technological progress may not be accelerating as dramatically as perceived, he argued that the current era is undeniably marked by “great discontinuity and sharp disruption” in political and geostrategic terms.

Mr Brennan, who was previously Chair of the Productivity Commission, also pointed to a combination of factors – geopolitical tensions, the retreat of US leadership, the return of inflation, disruptions in supply chains, and the economic impact of the pandemic – placing Australia at a precarious juncture. Historically, the nation has benefitted from external tailwinds, including booming global trade and resource-driven growth. “All those changes now look like significant challenges for Australia,” he said.

“We’ve seen the return of great power strategic rivalry and the retreat of the US from global leadership... but also the return of inflation, scarcity, and supply-side constraints. All of this comes on top of the challenges of an ageing population and very slow – by historical standards – productivity growth. None of these changes are benign for Australia."

Rethinking Australia’s economic identity

It’s clear that Australia needs more ambitious economic reforms now and in the future to secure long-term economic prosperity, lift productivity growth, and reduce overreliance on traditional industries.

Also speaking at the event, Pauline Grosjean, Scientia Professor in the School of Economics at UNSW and Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, critiqued the federal government’s spending priorities and the persistent focus on resource extraction over value-added industries that drive innovation, economic activity, and business investment.

Read more: Australia’s fiscal space at risk as federal budget deficit grows

“I think every country tends to cling to ideas about their national identity and critical junctures in history that shape collective ideas,” she said, reflecting on Australia’s national focus on mining, manufacturing, and primary sector dominance rather than developing high-growth areas like clean energy, critical minerals processing, or the education sector.

“So this obsession with mining and manufacturing and that primary sector and culture... large chunks of the budget and large chunks of COVID spending [are] spent in steel mills, smelters and digging stuff out of the ground, and not even transforming it.”

This, she said, is leading to missed opportunities to invest in renewable energy, zero emissions technologies, and industries that could enhance labour market resilience, GDP per capita, and Australia’s positioning among OECD peers.

Australia’s economic growth policies must be backed by research

Given these changes, economic policy must be guided by strong evidence and research-backed insights. However, Professor Greg Kaplan, co-founder of e61, who spoke as part of a panel session at the event, highlighted the structural gap in Australia’s policy ecosystem – the lack of integration between academic research and policymaking.

Unlike nations where research institutions and government are more closely integrated, Australia has not consistently drawn on cutting-edge economic insights to inform policy. “There traditionally hasn’t been a culture of communication between academia and policy, like we see in some other countries. In Australia, there’s less of a revolving door between research expertise and policy expertise – they’re somewhat siloed,” said Prof. Kaplan, who also serves as Alvin H. Baum Professor in the Kenneth C. Griffin Department of Economics at The University of Chicago.

“I think there’s also a sense that economics and economic research went out of fashion for a while… there has not been the same sort of cultural, social emphasis on developing strong research tools and using them for public good as you say in other countries,” Prof. Kaplan continued.

Mr Brennan reinforced this idea, emphasising the need for broad collaboration among academia, business, policymakers, unions, and community groups. “We need a broadening of the gene pool,” he said, advocating for diverse voices in public policy.

UNSW Sydney’s partnership with e61 aims to bridge this divide, injecting fresh economic initiatives into policymaking. At a time of economic uncertainty, this collaboration represents a strategic investment in Australia’s economic growth. “This is just the beginning,” Mr Brennan said. “We are very proud, very excited – not only of what we think this can achieve for e61 and UNSW but also for the broader nation, at a time when the importance of ideas is definitely so great.”

Five priorities to grow the Australian economy

The e61 and UNSW Sydney report, The Rising Isolation of the Island Nation: Five Economic Themes That Will Dominate the Next Parliament, details key economic themes that will be critical for Australia’s new Parliament to address and resolve.

Australia’s policy challenges today are as significant as at any time in nearly half a century, said Scientia Professor Richard Holden from the School of Economics, at UNSW Business School, and co-author of the report. “This report highlights five economic themes that will shape Australia’s policy debate in the life of the next Parliament and beyond,” said Prof. Holden. “We hope it will assist policymakers as they adapt to the new global order and tackle domestic pressures by framing the big policy challenges and identifying where policy needs to adapt.”

These five economic themes will be paramount for the new Parliament to grapple with:

1. Negotiating a new global order: As the world moves away from a rules-based system (the current political, legal and economic framework governing international relations), Australia must leverage its comparative advantages in security and resources to its geopolitical and trading partners. In particular, Australia must find opportunities in a strategic move to ‘‘friend-shoring’’ – integrating supply chain production more with trusted trading partners.

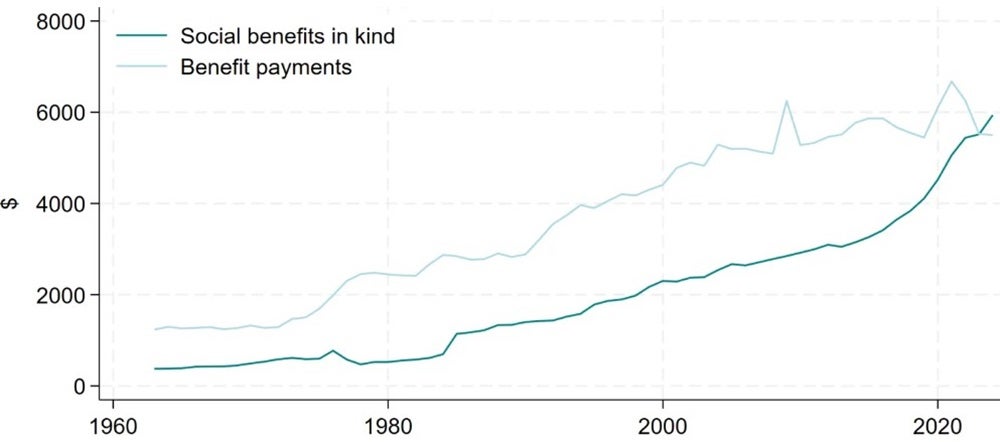

2. Re-examining a high population growth model: Australia has one of the highest population growth rates in the developed world, up by 35% in the past two decades (OECD average is just 13%). But this high-growth approach faces political pressure, in large part due to rising housing costs. With both major parties seeking to slow the rate of immigration, policymakers must rethink strategies to support an ageing population while maximising the benefits of skilled migration.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

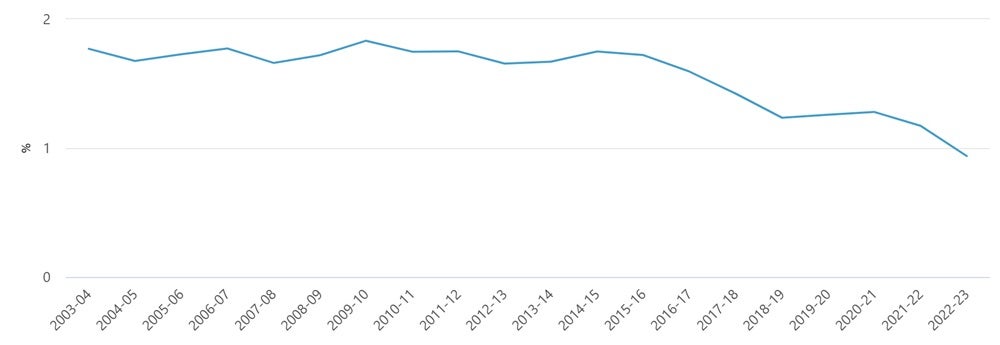

3. Boosting productivity growth: Australia’s productivity performance has been flat since the start of COVID-19. With changing global and domestic opposite of conditions, it is imperative we address productivity challenges, including low job mobility and a growing care sector.

4. Restoring fiscal sustainability: Australia’s budgetary pressures are set to grow, and future budget surpluses are at the whim of iron ore prices and reliant on bracket creep. Restoring fiscal sustainability via a balanced budget and low debt can help Australia weather global shocks.

5. Achieving a sustainable intergenerational bargain: Without addressing housing affordability, fiscal pressures, and improving productivity growth, Australia risks leaving younger generations worse off than their parents and grandparents.