The state of the nation: Key challenges for Australia’s economy

With stubborn inflation complicating the RBA’s tightrope walk, UNSW Business School experts zero in on pressing concerns about productivity and unemployment

While Australia weathered the pandemic better than many countries, questions about its recovery and handling of high inflation are tempering the economic outlook. Getting inflation and employment settings right will be critical, experts say – and some pain will likely be necessary.

Bruce Preston, Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, said that while many Australians are facing a challenging period, the economy has managed well in the broader context. However, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is now facing a critical moment in its bid to engineer a soft landing.

“My hope is that as the economy’s excess demand moderates, we’ll see some small adjustments in the labour market that reflect it returning to a state nearing long-term stability consistent with price stability,” he said. However, he cited some pressing concerns on the horizon.

“I worry that if it turns out the Reserve Bank has been overly optimistic, there’ll be a lot more inflation entrenched in the economy and people’s inflation expectations, and it’s going to require perhaps some additional interest rate rises that might not have been warranted had they acted earlier.”

Strong recovery, weak growth

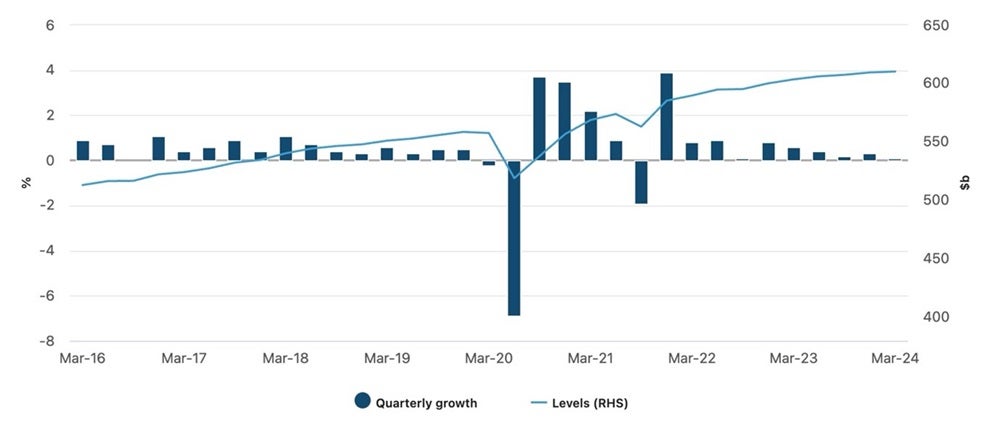

The big-picture economic outlook includes continued “relatively lacklustre” growth in Australia’s gross domestic product (GDP), which has grown by just 0.1% in the March quarter, according to Dr Nalini Prasad, senior lecturer in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School.

Gross domestic product, chain volume measures (seasonally adjusted)

“Growth has been subdued as inflation and higher interest rates have reduced demand,” she explained. “This has been particularly true for households, with homeowners seeing their mortgage interest rates climb by more than four percentage points and renters seeing noticeable increases in rents.

“As a result of this, consumption has been weak. Households appear to be reallocating their spending towards essential goods and services (think electricity, health care and rents) and away from discretionary items (think restaurants and holidays).”

Prof. Preston emphasised how important it is to place Australia’s economic position in the context of its recovery from the monumental challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. “It was a significant macroeconomic development that put a lot of stress on the Australian economy, and I think we handled that particularly well as a nation,” he said.

“We had a global pandemic in which we shut down a range of different sectors to protect public health and the economy. The idea that we’re going to walk away from that as a society without paying some economic cost is, I think, an overly optimistic one.”

Ongoing inflation concerns

While inflation has been cooling in Australia, the process has been slow, with the Consumer Price Index hovering above the RBA’s target band of 2-3% for three years. The RBA now expects inflation to reach the top of the band at the end of next year.

Should inflation keep falling, the RBA will likely keep the cash rate unchanged for the rest of 2024 until it has more information about the state of the economy, according to Dr Prasad.

“One thing that concerns me on the inflation front, and what I suspect the RBA is watching, is what is happening to services inflation,” which remains too high, she said.

“Tight rental markets have led to high rental price growth, and growth in insurance premiums has been rapid,” she added. “Changes in prices in these services tend to persist for long periods of time, so this is likely to continue to exert upward pressure on inflation.” Other services sectors, like holidays, restaurant dining and home maintenance, are also experiencing high inflation.

“A big part of the cost in delivering services is labour costs,” Dr Prasad explained. “Given inertia in wages, it will likely take some time for inflationary pressures from higher wages to dissipate. To moderate inflation growth, it would be ideal to moderate services inflation. The RBA has increased interest rates by a lot to bring down inflation, but it needs to remain vigilant to what is happening to services inflation.”

RBA’s narrow path

According to Prof. Preston, there’s an important question, and now a public debate, over to what extent the RBA’s goals are feasible. “The bank is in a challenging place: inflation’s high, but the labour market is robust, and that’s something to celebrate,” he said. “They’ve been very much concerned with maintaining the gains that have been made on the labour market side while bringing moderation in inflation.”

However, labour market outcomes reflect the level of demand for goods and services, and based on recent data, the RBA has judged that there is still excess demand. “I think they’re alert to the fact that perhaps the current state of the labour market is unsustainable and are worried about how to manage that,” Prof. Preston said.

“It will require slowing the economy to ensure that demand declines by some amount to be consistent with current supply conditions, which are determined by productivity growth and marginal cost structures in firms,” he added. “A lot of the debate is about, well, what kinds of interest rate rises would be required to bring that situation about?”

Read more: Sustaining Australia’s economic success: A roadmap for the future

Indeed, Prof. Preston contends that part of the rising price levels and associated cost-of-living crisis are necessary adjustments following a decline in living standards because of the partial economic shutdown.

“There’s another discussion to be had, though, about the policy response – we had very aggressive monetary and physical policy responses, and, in the event, they were perhaps too aggressive,” he said. This response added excess money to the system that has put upward pressure on inflation, with too much money chasing too few goods. “The way that gets resolved is a higher price level.”

Labour market tightness

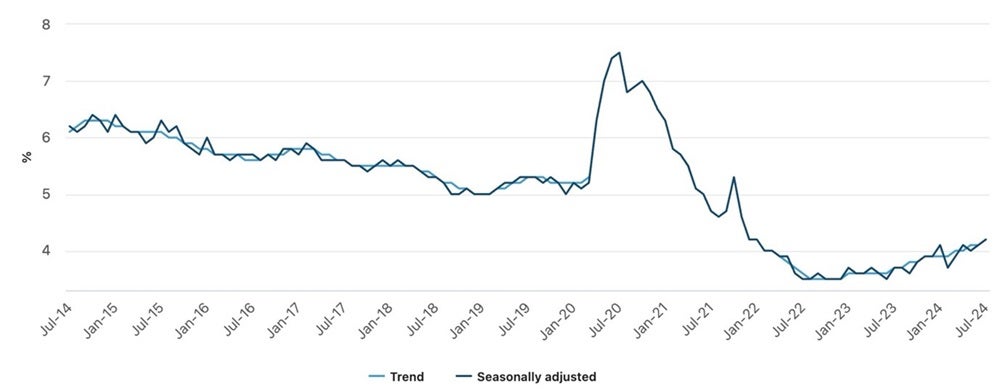

Meanwhile, unemployment in Australia is maintaining historically low levels, although July figures showed the unemployment rate continuing a slight upward trend to 4.2%. Business surveys show employers are still struggling to find sufficient labour to produce enough goods to meet demand.

The unemployment rate

“While the labour market is still tight, there are small signs that there might be some loosening in the future, with job advertisements and vacancies coming down,” said Dr Prasad. A looser labour market would help to cool inflation, but this is unlikely without higher unemployment that would, in turn, lead to lower prices and lower wage growth.

“I think the risks of a potential recession are low until we see a large increase in unemployment,” she said. “There would need to be a large shock hitting the economy to see large increases in unemployment.”

As Prof. Preston pointed out, another concern stems from people’s perceptions of how they’re doing, which are not positive. “Not surprisingly, that reflects the fact that rising prices reduce the purchasing power of household budgets and makes people feel poorer.”

“Despite the health of the Australian real economy, at the end of the day, the ability to have stable inflation depends on a balance of supply and demand,” Prof. Preston said. “My sense is that these very low levels of unemployment are probably inconsistent with long-run stable inflation.”

Gambling on good outcomes

Prof. Preston said these challenges illustrate the RBA’s difficult path to achieving its goals of sustainable inflation and full employment. The economy is still dealing with the repercussions of supply-side pandemic disruptions.

“My view is, to the extent that there’s still evidence of a situation of excess demand, the bank probably hasn’t done enough, and that some additional interest rate rises will be required,” he said. “I haven’t seen a convincing statement by the bank defending why that is not the case.”

Read more: Alan Kohler: market distortions are fuelling Australia’s housing crisis

Notably, the bank’s own forecasts don’t have inflation falling back into the 2-3% target range. “They’re meant to be targeting the midpoint of that band, and I guess you would hope to see in their own forecast that under their current policy plans, inflation would be returning to that centre point in a reasonable timeframe, and we’ve yet to see that,” Prof. Preston said. “At this point, they’re anticipating that inflation should hopefully fall to that midpoint in 2027; is that a success or a failure?

“The policy strategy is a bit of a gamble on an unexpectedly good outcome, and I worry that if faced with a bad outcome, interest rates might have to be increased by even more than some other countries have done,” he added.

Public debt picture

Another factor adding tension to the inflation discourse is growing public debt levels, particularly in a higher-interest-rate environment. Prof. Preston said he’s “reasonably optimistic” about this, noting that Australia entered the pandemic “having had many decades of reasonably prudent fiscal policy, at least relative to peer countries.

“We had very low gross and net debt going into the crisis, which afforded a lot of latitude to use fiscal policy as a tool for stimulus,” he added. “Of course, that saw the public debt rise considerably over the acute phase of the pandemic, but those levels are still pretty modest relative to many other countries.”

However, he questioned whether current policymakers are approaching debt considerations with the same prudence as they have in the past. With budgets now forecasting structural deficits, tax revenues will be insufficient to cover current spending needs, and how that plays out over the next five to 10 years will be critical.

According to Dr Prasad, these debt levels are expected to increase significantly in the next few years. “Since the pandemic, the state governments in Australia have run large budget deficits, recording some of the largest deficits in the developed world,” she said.

“The risk with these large deficits is that it might push more money into the economy and increase demand when the RBA is trying to reduce demand to bring down inflation,” she added.

What state governments do with borrowed money also matters. “Some of the borrowed funds have been used to fund infrastructure projects, which we think will expand the productive capacity of the economy in the long run, but in the short run, this increase in money hitting the economy risks contributing to more inflationary pressures,” Dr Prasad said.

Productivity is key

Dr Prasad called slowing productivity growth the most significant of the challenges Australia faces into 2025. “Productivity – or multifactor productivity to be exact – measures the amount of goods and services that can be produced by a given amount of labour and capital inputs,” with increased productivity leading to better living standards, she explained. It allows wages to rise without fuelling inflation further.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

The problem is that Australia has seen broadly flat productivity growth for the last five years, compared with nearly 2% growth in the late 1990s. “Increasing productivity will be hard: it requires increasing the skills of workers, improving business dynamism and looking at how the labour force can change with an ageing population,” Dr Prasad said. “But, without improvements in productivity, living standards in Australia will not increase at the same rate as in the past.”

This concern dovetails with Prof. Preston’s fear that more rate rises will be required if the RBA has been overly optimistic. “I think that raises the likelihood that the real economy, our ability to produce and how much labour is required to produce that, is going to take a bigger hit than it might have otherwise,” he said.