Alan Kohler: market distortions are fuelling Australia’s housing crisis

Homeownership has always been key to prosperity in Australia, but Alan Kohler says out-of-control house prices threaten to destroy that heritage

Surging home prices are more than just a financial issue – given the importance of homeownership in Australia, they are a societal crisis. Fixing things will require a difficult rebalance after 25 years of market distortions, and getting the timing right is essential.

It’s essential to recognise the social consequences of unaffordable housing in conversations about the property market’s massive role in Australia’s economy, according to financial journalist Alan Kohler. In a recent discussion at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, presented in partnership with UNSW Sydney, he explained how distortions in the market since 2000 have already taken a substantial social toll and, unchecked, will only worsen.

“It’s come to the point where it’s changing how wealth is created; it’s no longer the case that you can easily make wealth in any other way than housing,” said Mr Kohler, who was discussing his recent Quarterly Essay, The Great Divide: Australia’s Housing Crisis and How to Fix It, with Richard Holden, Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School and President of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia. Now, where a person lives determines how much wealth they have – and inheritance takes on a greater importance in Australian society.

“It’s no longer possible for somebody who doesn’t have reasonably wealthy parents to buy a house,” he said. “It’s as simple as that. And it’s a fundamental change to Australian society.”

A ‘new class of working poor’

It would take 20 years of unchanged house prices to undo the level shift that’s distorted the sector over the past 25 years, Mr Kohler explained. Meanwhile, the problem is compounded as new generations demand the same growth their parents enjoyed, according to Prof. Holden, who compared this need for growth in home equity to “a treadmill we can’t get off”.

Those who can’t even get on the treadmill – children of renters, for instance, whose parents can’t help them obtain equity – will be cut off from economic growth. But even younger families that can acquire property are having difficulty meeting their mortgage-servicing obligations, thanks to higher interest rates and debt costs.

“You’ve got to earn a lot of money for that, and the young families with young kids who are doing that haven’t got any money for anything else,” Mr Kohler said. “So, suddenly, there’s this whole new class of working poor, who’ve got decent jobs and are paid reasonably well, but they’ve got no money.”

Read more: Should we convert empty offices to address housing shortages?

The dearth of housing is an especially frustrating problem for Australia, which has plenty of land and one of the lowest population densities on the planet. Mr Kohler traced the crisis to 2000, when house prices started taking off.

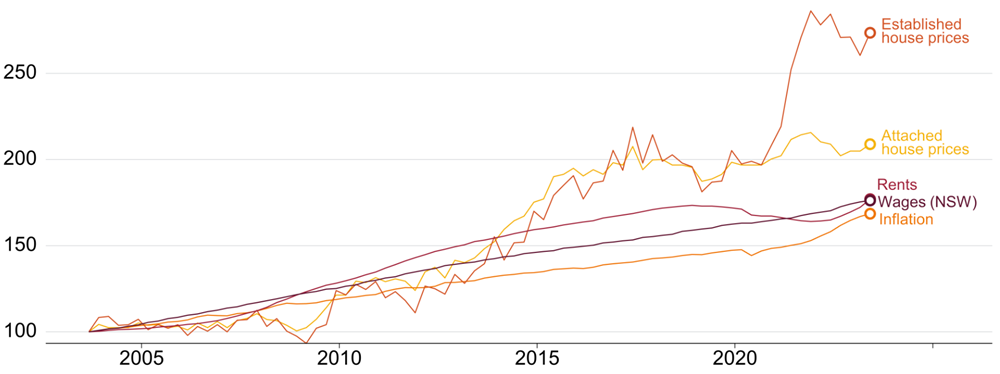

Before then, prices had uniformly risen at the same rate as both incomes and gross domestic product (GDP) in Australia; after 2000, the rate at which house prices rose doubled. According to Mr Kohler, the introduction of the capital gains tax discount in September 1999 was a “psychological lightbulb moment for the nation” that, combined with the availability of negative gearing, represented a “fantastic tax dodge, basically”. Responding to these new incentives, investors supercharged demand in the housing market.

Meanwhile, immigration began having an outsized impact, outstripping housing supply between 2005 and 2015. While both these effects have faded over the years, “that decade is the period when housing in Australia became unaffordable”, Mr Kohler explained.

As a result of these distortions, the ratio of house prices to annual income has exploded; prices are now at eight times income, compared with four times income in 1999. That translates to a median house price in Sydney, for example, of more than $1 million, when it should be $500,000.

A ‘net-zero moment’ for the housing crisis

The lack of affordable housing significantly impacts people’s lives, to the point that housing and property are now the source of a new class divide in Australia. If the trend continues, renting will become a much more prominent aspect of Australian society.

“More and more people, particularly young families, will have to get their heads around the idea that they will never own a house and will rent all their lives,” Mr Kohler said. The effective loss of property acquisition as an access point to financial growth will have substantial economic implications for Australia. “As a society, we may not be able to do that anymore.”

However, solving these problems will take a more concentrated effort than policymakers have mustered thus far, Mr Kohler said, acknowledging that “any solution on housing that is easy and popular won’t work”.

Read more: Are you paying more interest on your mortgage than you think?

First, because of the importance of the housing market to Australian voters – and to those making decisions on housing policy – it’s essential to build a national consensus around a solution.

There also needs to be a clearly defined goal to ensure accountability and measure progress, Mr Kohler said; current efforts “grabbing bits of policy” aimed at improving housing affordability are not enough. He contrasted the housing issue with climate change, where the global ambition to meet a net-zero goal provides accountability when efforts fall short.

The housing crisis, therefore, needs its own “net-zero moment” and must clearly define its goal, Prof. Holden suggested.

According to Mr Kohler, the goal must be to return the house price-to-income ratio to the more sustainable pre-2000 level of four times income.

House prices have soared above wages and rents and increased faster than inflation

Tackling the supply-demand imbalance

Attempts to tackle housing affordability have generally focused on supply-side efforts, such as reforms to zoning restrictions and medium-density rules, and policies aimed at curbing demand through tax reform. However, previous political missteps on demand-side measures mean that current engagement focuses primarily on shoring up supply.

According to Prof. Holden, this approach of picking and choosing between supply and demand is insufficient for a problem that requires a more holistic solution. Mr Kohler agreed, saying it’s unlikely Australia can densify its cities to the extent needed to solve the issue from the supply side only, thanks in part to political challenges around changing zoning laws.

Moreover, housing approvals per capita are at all-time lows not just in Australia but in advanced economies generally, as surging immigration continues to be a global issue. However, just 5 per cent of people migrating to Australia work in housing construction. In other words, current settings are increasing the population without augmenting the construction industry’s capacity.

Read more: The great construction company collapse: when your builder goes bust

What Mr Kohler suggested was “not some arbitrary reduction in immigration numbers, which can so easily be tied to xenophobia or racism”, but instead a transparent linkage relating immigration to construction capacity, such as by exposing for public comparison the numbers of new migrants and new housing approvals.

“After a while, it will become clear there’s an imbalance, and then something might be done about it,” he said.

Any solution must also reflect the importance of housing markets to Australia’s financial stability, including the big four banks’ high exposure to the residential housing market. And while prices won’t rise unsustainably forever, Mr Kohler emphasised that the trend needs to do more than stop.

“We need to aim at getting it back to where it was, so that Australian society can stop being so distorted socially.”

Solutions and challenges in Australia

To achieve a more sustainable price-to-income ratio, however, it’s vital that the necessary convergence doesn’t occur too quickly, as an immediate 50 per cent correction in house prices would be disastrous for the financial system’s stability. For instance, the global financial crisis happened when US house prices fell 30 per cent between early 2007 and 2008.

In Australia, the main influences on house prices are not government policies but interest rates and the activities of the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority, Mr Kohler explained. For example, the prudential regulator prompted an 8-9 per cent fall in house prices in 2017 by cracking down on bank lending to investors, and prices fell in the early 1990s because interest rates rose to 7.5 per cent.

More recently, house prices fell during the COVID-19 pandemic, but the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) ’s reduction of the official cate rate to virtually zero stopped the fall, Mr Kohler explained. Sustained low rates then prompted prices to rise until the RBA brought rates to their current level of 4.35 per cent. Increasing the cash rate is, therefore, an effective means of suppressing growth in house prices – but it’s also a particularly tough economic sell.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

Another aspect of the problem is that the balance of power in rental markets is “far too skewed towards landlords”, Mr Kohler said. Increasing tenants’ rights, as state governments in Victoria and Queensland have attempted to do, helps redress this by incentivising landlords to exit the market, removing that distortion.

However, a national approach is needed. Mr Kohler suggested a move to centralised planning, similar to the UK’s approach, noting that Australia’s current system of state-level delegation to local councils has spawned “complete chaos across the country” in attempts to reform housing.

“I’m inherently a federalist,” Mr Kohler concluded. “I’d like to see the federal government take control and say, ‘We are going to densify the cities because that’s what we have to do. And for the people who live in Mosman, sorry, but there are going to be some blocks of flats now.’”