How compassionate leaders improve business performance

Measuring leaders’ empathetic qualities against employee motivation is one way to quantify its impact on business performance, write IMD's Paolo Cervini and Gabriele Rosani

This article is republished with permission from I by IMD, the knowledge platform of IMD Business School. You may access the original article here.

In our daily lives, all of us appreciate the power of kindness. Its value lies in how it can create positive feelings both for givers and takers and trigger constructive actions, thoughts and emotions. Yet, in the world of business, kindness is a rare and often unacknowledged commodity. Instead, toughness, assertiveness and self-interest have been considered the corporate benchmarks of behavior.

But times change, and in the world of modern leadership, these traits are now widely seen as negative. Kindness is enjoying a renaissance. The number of Google searches with the keywords kind leadership has multiplied threefold in the last five years; several pivotal articles and books have made the concept familiar to management experts and practitioners, and leaders such as Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and businessman and Harvard Business School lecturer Hubert Joly, as well as politicians like New Zealand’s former prime minister Jacinda Ardern, are well-known proponents of empathetic leadership styles.

Despite the good intentions to #BeKind and inspiring examples of kindness at work, it’s still far from being sewn into the fabric of most companies. Indeed, kindness is often simplistically misinterpreted as “being polite”, which misses the deeper importance of ensuring a psychologically safe space for debate, listening to the needs and passions of the individual and helping them to unleash their full potential. The issue with this is that most executives still perceive kindness as vague, soft, and intangible and struggle to see its connection to corporate performance – even though many academic studies suggest that the link is abundantly clear.

The supposed lack of measurability also opens the door to sceptics, with doubt and criticism creeping in behind the scenes. “Yes, kindness is the new fashion at our HR office. They preach that we need to become ‘kind leaders’, but frankly I have to first think about my KPIs,” an executive at a large European corporation told us. Blunt and unapologetic, this remark makes it clear that the only way to win over sceptical executives is to have KPIs that incorporate kindness and thereby show the business case behind it. But how?

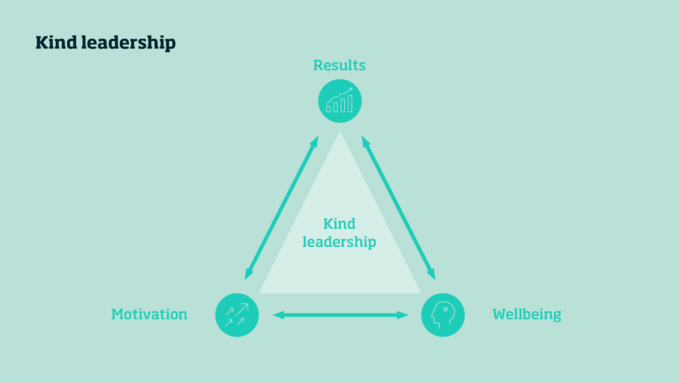

We discussed the concept with a number of leaders and were especially inspired by conversations with Guido Stratta, head of people and organisation at the power company Enel. He inspired us with the idea of a Kindness Triangle (below). At the base of the triangle are motivation and wellbeing indicators. At its top are business results. Every vertex of the triangle has an associated set of indexes, with analytical correlations linking the three vertices.

The logic is that kind leadership results in higher rates of trust and engagement in people, which in turn translates into improved company performance. A person who feels safe and empowered will have a strong intrinsic motivation to work with passion and enthusiasm, positively impacting the goals of his/her unit. This mechanism is not only theoretical but can (and should) be measured in practice.

The types of correlations between kindness, trust, motivation, and business results can vary depending on the industry and company context: a retailer may look at the relationship between passionate shop assistants, delighted clients, and revenues per point of sale, while an industrial company may look at the link between shift workers’ engagement, rates of absenteeism, and plant operation results in terms of defect rates. Regardless of any specificity, the benefits will be spread not only to people and organisations, but to the entire ecosystem, in a virtuous mechanism that feeds itself.

Having a more scientific approach can help HR leaders convince their more pragmatic colleagues in other units and functions about the power of kindness and its effect on measurable outcomes. The analogy with KPIs resonates well with analytically minded executives from operations to sales. Combining “kindness” and “indicators” makes it a powerful label easy to grasp and pre-empt the typical objections about lack of objectivity, measurability, trackability and auditability.

Read more: How can HR best help employees with domestic violence?

Based on our research and direct experience, there are four main steps to quantify kindness and its impact on business:

1. Measure leaders’ kindness. In our previous article on building organisational trust, we introduced the Trust Behavioural Index which summarises, for each manager, their individual score on different components such as credibility, vulnerability, and selflessness. This is created through a set of underlying questions that are scored anonymously by peers and direct reports. For example, at SAP, managers have a Net Promoter Score on leadership trust – a core index of how they are viewed by direct reports. Leaders who are kind are seen as more trustworthy by their employees, which has a positive impact on motivation, well-being, and engagement.

2. Compare leaders’ kindness with their employees’ motivation. Employees are surveyed on their motivation with questions around purpose, autonomy, and relationship. Results by unit (or sub-unit) are compared with the unit leader’s individual score on the Trust Behavioural Index. In the companies and units where we ran the correlation, we found consistent links between kind leaders and motivated employees.

3. Link employee motivation and business performance. To convincingly show the link between kindness, motivation and business results, anecdotal evidence is not enough. Each unit should analyse the link between higher motivation indexes and measurable business metrics (like sales or operations efficiency). Granularity of analysis is important to avoid dilution. We encourage companies to conduct this analysis across all divisions (horizontal granularity) and within one division to cascade into sub-units and teams (vertical granularity). For example, Google’s well-known Project Aristotle analysed 180 teams to investigate what drives team performance, finding correlation with multiple motivational patterns.

4. Track progress balancing “lag” and “lead” indicators. When correlating the link between leadership behaviours, employee motivation/wellbeing, and business performance, it’s important to consider the delay between one action and the impact on the following layer. For example, lag indicators measure the current motivation and wellbeing (e.g., absenteeism, turnover), while lead indicators measure concrete actions taken by leaders to drive the future motivation state of their employees (e.g., team retrospectives, purpose sessions, the removal of the needs for authorisation).

One key success factor to scale the approach is the availability of analytical power, especially within the HR function commonly in charge of driving the cultural and leadership evolution of the organisation. While pioneers like Alphabet have spearheaded analytics to make HR more data-driven, many traditional firms still do not have the skills, nor the capacity, to understand the various dynamics at work around kindness and unearth hidden patterns. This presents a challenge to HR leaders. To become more credible with their colleagues, they must undertake a deep transformation coupling their traditional soft power with the hard power of metrics and analytics.

Our hope is that having common metrics for kindness, trust and motivation will contribute to achieving sustainability at scale. Caring for the planet requires caring for the people who live on it (from employees and their families to suppliers and local partners and communities). Indeed, there is an urgent need to have data and indexes that reinforce sustainability ESG metrics, especially for reporting the “S” dimension (currently overlooked in favour of the more easily measured “E”). A standard kindness benchmark would enable different firms in different industries to compare their performances in the same way as traditional KPIs do so for operational efficiency or financial performance.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

The approach we have described in this article is a call for action. Think of a future where a company reports its human results for employees, suppliers, and partners alongside business and climate results, vis-a-vis other companies in the sector and beyond. While this may seem a distant and unattainable prospect, pioneers are paving the way for a revolution waiting for a broader coalition of leaders to jump on board – and so, thanks to the advance in digital tools and data platforms and ecosystems, the journey is more feasible than ever.

Paolo Cervini is Vice President of Capgemini Invent and Co-leader of the Management Lab by Capgemini Invent. Gabriele Rosani is a Principal of Capgemini Invent and Director of Content and Research at the Management Lab by Capgemini Invent.