Why JobSeeker is too low despite improvements in unemployment

Even with the latest small increase, JobSeeker remains too low by overseas standards – about the lowest in the OECD, write UNSW Sydney's Bruce Bradbury and ANU's Peter Whiteford

One of the first things Labor’s Bob Hawke did on being swept to office in March 1983 was to lift the unemployment benefit in April, seven weeks later, without even waiting for his first budget.

One of the first things Labor’s Anthony Albanese did during the first week of this election campaign was to let it be known that Labor was no longer committed to lifting the unemployment benefit at any time up to and including his first budget.

A promise to review the payment made in the last election by then Labor leader Bill Shorten was no longer operative.

Hawke’s 1983 increase was the first of many. Over 12 years, the Hawke and Keating governments lifted the real value of unemployment benefits 27 per cent. Albanese said last week that Labor had no plan to lift what is now called JobSeeker in its first budget. Government debt was “heading toward a trillion dollars”.

The single rate of JobSeeker is A$642.70 a fortnight, about $46 a day.

Is JobSeeker enough?

Some job seekers get more. Single parents and those aged 60 and over who have been on payments for nine months can get up to $691 per fortnight. Partnered job seekers can get $585.30 each. There is also a small energy supplement of 63 cents to 86 cents per day and rent assistance offering single people renting privately up to $145.80 per fortnight and renters sharing with other people up to $97.20 per fortnight.

And for some months during the pandemic, the temporary Coronavirus Supplement introduced in March 2020 almost doubled the base rate. Calculations by the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods suggest this cut the share of JobSeeker recipients in poverty from 67 per cent to just under 7 per cent.

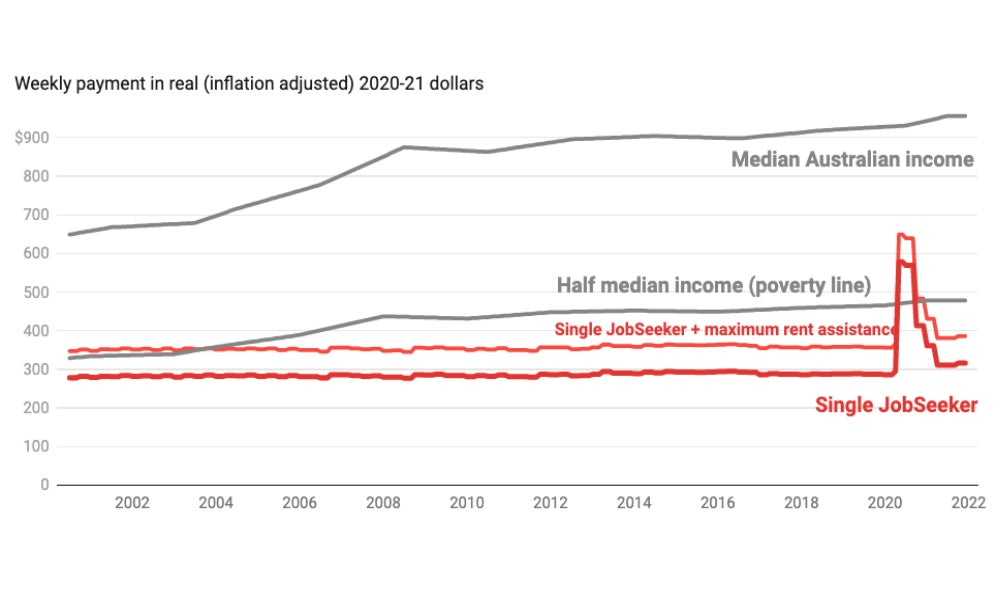

Newstart/JobSeeker compared to poverty line

But the boost was short-lived. By 2021 the supplement had been removed entirely and replaced with a much smaller increase of $50 a fortnight. Research by Anglicare found that, while it lasted, the supplement allowed families to pay rent, access nutritious food and avoid emergency relief services.

As shown in the chart, $50 a fortnight has done little to redress the extent to which people's living standards on unemployment benefits have been falling behind. For the last three decades, they have done little more than increase in line with prices, while the living standards of wage earners have grown strongly.

The base rate has fallen from 84 per cent to 66 per cent of the poverty line, defined as half the median income over that time, even considering the latest increase. And JobSeeker has also fallen further behind the minimum wage.

Newstart/JobSeeker as a proportion of the minimum wage

Even for those able to receive the maximum rate of rent assistance, unemployment payments have fallen from 57 per cent of the net minimum wage at the start of the 2000s to 50 per cent now. This is on top of a fall of four percentage points during the 1990s.

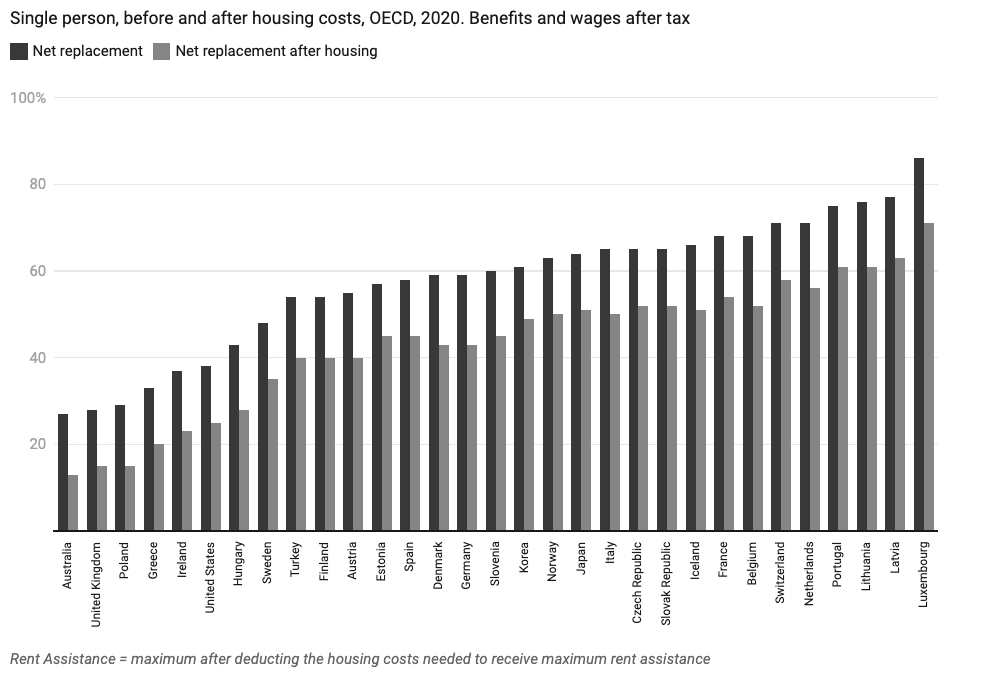

This makes it difficult to make a case that unemployment payments are generous enough to discourage job seekers from seeking the minimum wage. Compared to other high-income countries, Australia's JobSeeker “net replacement rate” is low, about the lowest in the OECD.

The net replacement rate is the assistance provided to a single person aged 40 who has been unemployed for two months as a proportion of the average wage.

Unemployment benefit net replacement rates

Australia’s minister for social services has argued these comparisons are not relevant because Australia’s social security system is based on different principles than those in most other countries.

Australian income support is unrelated to previous earnings. This is correct, but it does not change the fact that when Australian workers lose their job, their income drops by far more than workers in other OECD countries.

Moreover, when the government announced the $50 a fortnight increase in February 2021, the prime minister justified it by saying that this would move the replacement rate back to where it had been under the Howard Government. It would be: “41.2 per cent of the national minimum wage, which puts us back in the realm of where we had been previously”.

While this is similar to the replacement rate at the end of Howard’s term, it is nothing like the replacement rate at the start of the term.

But unemployment has fallen…

At just 4 per cent, unemployment is now much lower than the 5.2 per cent that prevailed at the time of the 2019 election when Labor promised to review JobSeeker.

But the number of people receiving JobSeeker and Youth Allowance (Other) is higher than it was back then; 935,000 people received these payments in February 2022, compared to 765,000 in May 2019. The reasons for this difference are complex, but a significant factor is that a very large share of people receiving unemployment payments are not required to seek jobs and have a reduced capacity to work.

Among them are people whose access to the disability support pension has been cut and Australians who would have been of pension age before it was lifted.

Read more: JobSeeker: how do Australia's unemployment benefits rank in the OECD?

What would Labor actually do?

On almost any measure, JobSeeker is too low, as the inquiry promised by Labor in 2019 would have discovered.

Labor’s present national platform talks about rewarding: “those who work hard to create a better life for themselves. Labor is the party for those who want to get ahead, as well as the party of compassion for those doing it tough”.

It goes on to pledge that: “Labor will make sure people who are looking for work get the financial support they need to live a life of dignity through a strong social security system as well as the support they need to find and keep a job”.

This offers some hope but, unlike in 2019, no guarantees.

Bruce Bradbury is an Associate Professor in the Social Policy Research Centre at UNSW Sydney, and Peter Whiteford is a Professor at the Crawford School of Public Policy at the Australian National University. A version of this article first appeared on The Conversation.