JobSeeker: how do Australia's unemployment benefits rank in the OECD?

With JobKeeper payments increasing marginally from April 2021 Australia now has the second-lowest unemployment benefits out of any OECD country, write UNSW Sydney's Bruce Bradbury and Australian National University's Peter Whiteford

Fifty dollars sounds like a lot. But the increase in the JobSeeker unemployment benefit announced by Prime Minister Morrison last week is $50 per fortnight, which is just $25 per week. It will replace the temporary Coronavirus Supplement of $75 per week, which is itself well down on the $275 per week it began at in March last year.

It’s hard to see the increase as anything other than a cut, especially when coupled with another change that will allow recipients to earn other income of only $75 per week before JobSeeker gets cut. That’s down from the present $150 per week. As the Prime Minister said, it’s better than it would have been if things returned to the level we had before special coronavirus provisions. At that time, recipients could earn only $53 per week before having their payment reduced.

But it’s not particularly generous. The Age and Sydney Morning Herald are quoting senior government sources as saying the $50 per fortnight increase in the rate was the lowest figure the party believed would be palatable to the public.

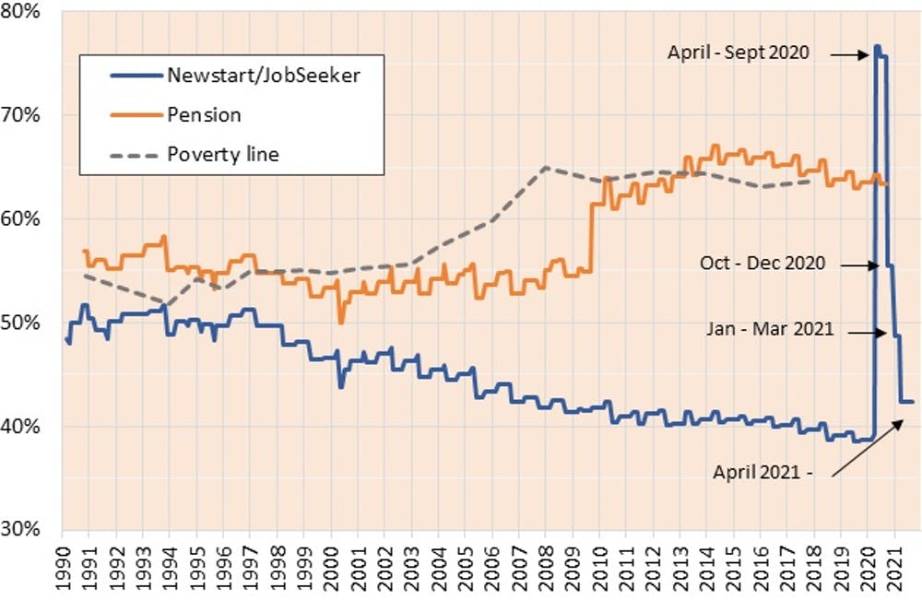

Morrison justified the increase of $50 per fortnight – rather than $150 (which would have kept what’s left of the coronavirus boost in place) or $100 or any other figure – by saying it will bring the payment to: "41.2 per cent of the national minimum wage, which puts us back in the realm of where we had been previously".

Taking account of taxes paid and superannuation received by minimum wage workers gives a slightly higher replacement rate of 42.3 per cent. That takes it back to roughly where it was at the end of the Howard government in 2007.

However, there’s no readily apparent reason why that should be a benchmark. During the life of the Howard government, the level of the single payment fell from around 50 per cent of the minimum wage to 42 per cent, meaning what’s proposed will return it to its lowest point relative to other benefits under Howard.

JobSeeker and age pension as a proportion of the minimum wage 1990-2021

What about the supplements?

Morrison also argued in his press conference JobSeeker is more adequate than the base rate would suggest because: "on top of that, if they’re receiving Commonwealth Rent Assistance, that payment would increase to $760.40; and on top of that, the average value of stand-alone supplements, the energy supplement and so on, is an additional $13.03. So the suggestion that anyone who was on JobSeeker is simply on that payment alone and there aren’t additional supports that are provided is not correct."

It’s true all people on income support receive the energy supplement (included in the figure above). But for a single person on JobSeeker, the supplement is only $8.80 per fortnight or less than 65 cents a day.

Many people do indeed get rent assistance, but after paying rent they become worse off rather than better off. That’s because to get the maximum rate of rent assistance for a single person of $140 per fortnight (9 per cent of the minimum wage), that person has to be paying around $310 per fortnight in rent. If that person is paying more, they get no extra help. The maximum is also lower for people in shared accommodation.

Private sector renters are amongst the worst off recipients of income support.

Other supplements such as the remote area allowance are indeed available but are of no help to people who do not live in remote areas and may be inadequate to cover the higher costs involved. Supplements for help with language and literacy are only paid to people in special education programmes.

Producing an average that includes supplementary payments most people don’t receive is inherently misleading.

How Australia compares

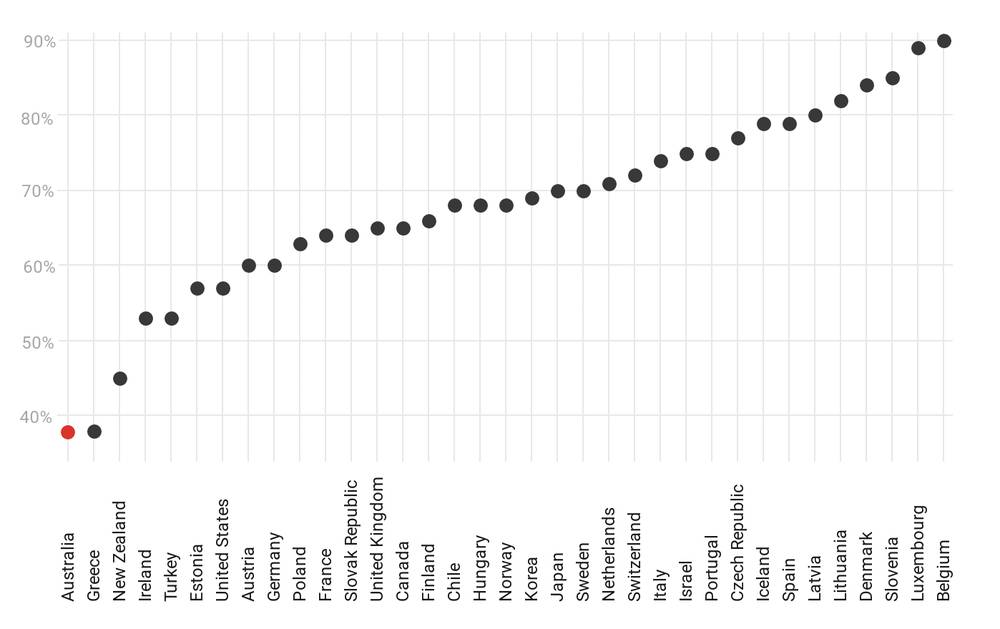

Net replacement rates measure the proportion of previous in-work income that is maintained after several months of unemployment. They are the benchmark used by the prime minister to compare benefits to the minimum wage.

Using two months in unemployment as the measuring point (and using the most recently published 2019 rankings) before the pandemic, Australia’s replacement rate was the lowest in the OECD — even after rental assistance was added in.

Unemployment benefit, share of previous income after two months

When the maximum rate of coronavirus supplement was briefly in force in 2020, Australia moved to around the OECD average.

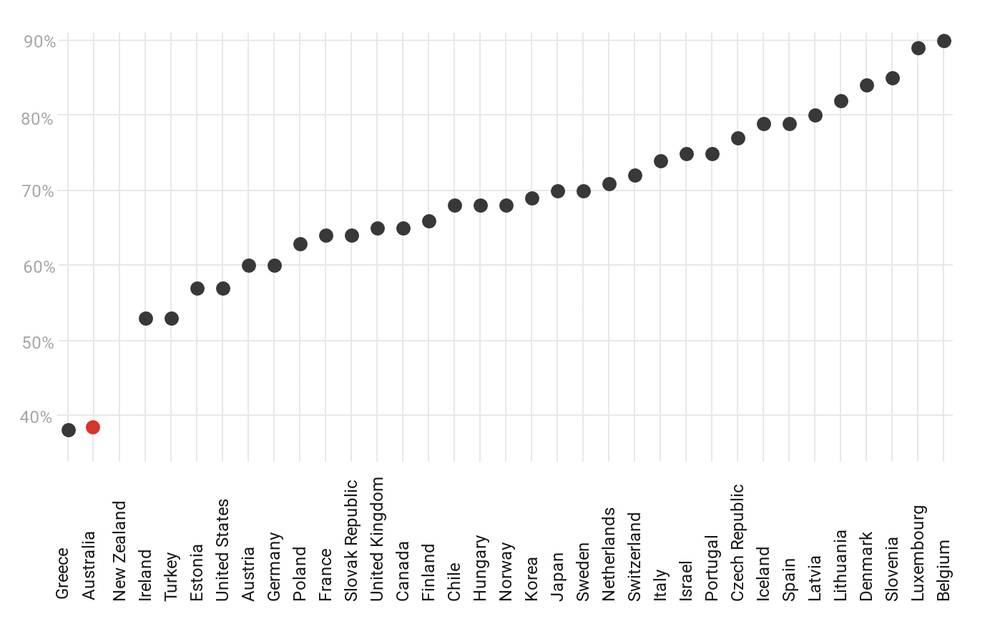

The new rate from April 2021 will move Australia from the lowest to the second lowest, ahead of Greece only.

Unemployment benefit, share of previous income, after Australian increase

It should be acknowledged Australia’s system is based on different principles from many other OECD countries in which workers and their employers make contributions to and withdrawals from unemployment insurance.

But the difference in philosophy does not change the brutal reality that when Australian workers lose their job, their incomes fall more than in almost any other high-income country.

Even after what the government has trumpeted as a historic increase, there will be few developed countries where people will be as worse off after losing work. Any permanent increase is welcome, but there is a long way to go.

Bruce Bradbury is an Associate Professor in the Social Policy Research Centre at UNSW Sydney, and Peter Whiteford is a Professor at the Crawford School of Public Policy at the Australian National University. A version of this article first appeared on The Conversation.