Want the best performance and productivity? Take a rest

Executives can learn how to optimise productivity and performance by studying the training routines of Olympic athletes, write IMD Business School's Susan Goldsworthy and Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff

This article is republished with permission from I by IMD, the knowledge platform of IMD Business School. You may access the original article here.

After a fraught build-up, the Olympic Games have concluded and athletes shared their journeys more than ever before on social media, which provided a unique window into the life of elite-level athletes as they neared the games. One striking aspect of this pre-competition preparation is the regimens that the competitors universally follow. After weeks of final training, in the days before events, sportspeople rest and recover in order to peak at exactly the right moment. It’s the perfect reminder of how the human body needs time to repair itself.

At its essence, the sports world’s recipe for success is simple: disciplined preparation (both mental and physical) plus rest and recovery equals performance. This also holds true for the business world. Good executive leadership recognises the need to strategically train both themselves and their teams, including allocating time for rest and recovery, in order to perform at their best.

The problem is that the business world all too often thinks of human productivity through a mechanistic lens. Measuring worker productivity by hours logged, not by the quality of what is delivered, has become the norm. Enterprises emphasise the “engine of growth” or refer to “cogs in the wheel of industry”.

Too often, with the pandemic making telework the norm, the issue of workforce productivity is tension-filled. Telework provides many positives, and the research shows that the quality of work overall has improved during the pandemic.

Recent research from McKinsey shows that most C-suite executives report an improvement in individual and team productivity and employee engagement compared with pre-Covid-19. More than 80 per cent of those interviewed reported no change, an improvement or a significant improvement across the five areas. However, managers don’t perceive worker productivity in the same ways as C-suite executives, leading to a lack of trust. Workers sense this and are always “on”, taking few breaks and feeling constant pressure to be responsive. Without downtime, they are no longer able to perform at their best or to make the best decisions.

According to research conducted at IMD (by Susan Goldsworthy) with more than 1,000 executives from mid- to large-sized companies around the world, between 40 per cent and 70 per cent of people feel they are operating in survival or burnout mode. It underscores the need to recognise that the human body is not a machine. Instead of measuring productivity by hours logged at a desk, leaders should gauge production by the quality of the output, just as athletes are judged not by the length or duress of their training regimens, but by performances in competition.

Read more: Four effective and practical ways leaders can truly do more with less

It’s imperative for executives to create environments in which their entire teams feel accepted and flourish. Here are five preliminary steps leaders can take:

1. Change the narrative

Tell a different story about your company and its deliverables, one that doesn’t focus on the number of hours put in but on the quality of performance aligned with the bigger purpose. This is difficult, but reaps big benefits. Language dictates not just the story of an enterprise, its journey, its values and vision/mission, but also the way it acts. Changing terminology to emphasise living systems, not machinery, helps change the story, and thus the way we act. This is even more critical in the context of the ecological crisis we are all facing. Rather than emphasising efficiencies or productivity, language that instantly evokes a machine, instead use language to reflect human capacity and capabilities, creating the space to enable others to fulfil their potential and flourish.

2. Provide clear expectations

How the journey is framed is as important as how that journey transpires. To borrow from the sports world, if your expectations are only to get to the quarter-final of a major tournament, and your team succeeds, the next morning you have to entirely reset what is expected of the team in order to advance. On the other hand, if you expect to get to the final, then the quarter-final win is just one step on the path towards the ultimate goal.

Taking a longer-term perspective, one of the next decade for example, aligned with the purpose and sustainability goals, creates a learning environment where people feel inspired to contribute to the bigger picture and make a difference.

3. Lead by example

Many leaders are like the hamster on the wheel. They are running and running but making little progress. At the end of the day, they are often exhausted and also feel as though they have not achieved as much as hoped. These feelings are a sure sign that they are in survival or burnout mode. It’s imperative to find a better balance between professional and home life as part of the rest and recovery cycle. It’s normal and desirable to have a life outside work, to have dedicated family time. It’s fine to have a hobby. Our best ideas often come when we are doing something else. And it’s vital that leaders demonstrate that it’s more than just ok to recharge, it is expected.

4. Let people be heard

A danger for leaders is when they only want to hear the positives. In such environments, there is an artificial harmony with all the less-than-happy emotions repressed. This is unhealthy and will affect engagement and performance. Letting people share what they are feeling or going through without trying to problem-solve feeds a sense of acceptance that strengthens teams in numerous ways. Neuroscientific research with MRI scanners shows us that when people share how they are feeling, in a non-judgmental environment, it actually decreases the negative emotion in the amygdala. Knowing that people can be themselves and be accepted for who they are not what they do is fundamental to unleashing potential and performance.

5. Introduce a no-blame culture

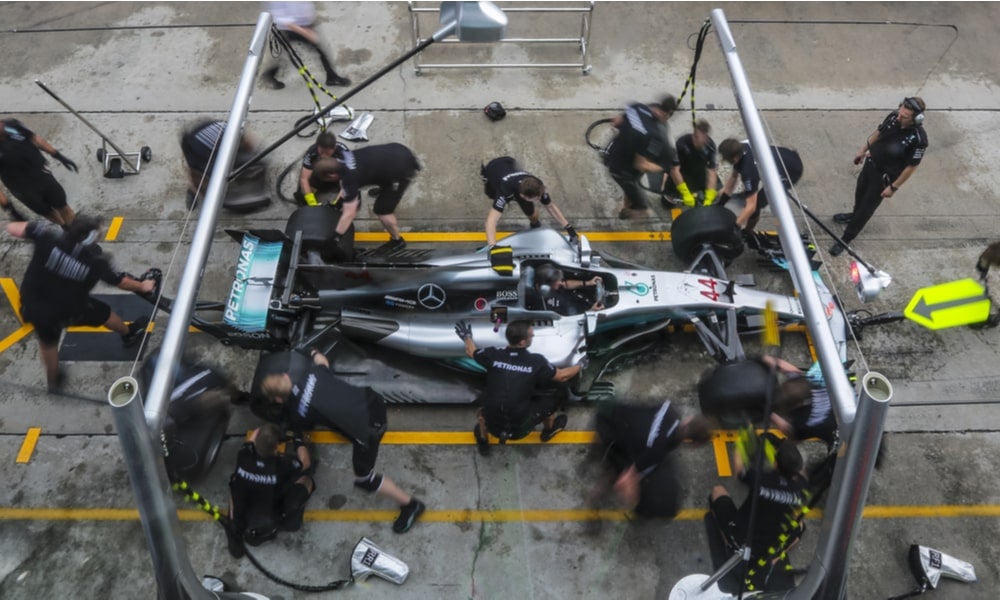

We are all human and we all make mistakes. It is integral to how we learn. So-called failures are actually natural steps on the path to success; the only failure is if we don’t learn from our mistakes. For example, the Mercedes Formula 1 team is known for its “no blame” culture. After a disastrous qualifying at the Turkish Grand Prix last year, The World Champion driver Lewis Hamilton sent out a tweet saying: “Today, we didn’t get it right but it’s days like today we learn the most, so it’s actually a good day! Tomorrow is going to be even tougher but we win and lose as a team…”

Most of us do not plan to deliberately annoy or frustrate someone or mess things up. Most people’s intentions are positive even if their impact may not be. How leaders respond in adversity is a mark of their leadership ability and makes a significant difference to the wellbeing and engagement of others.

The business world, just like the Olympians and Paralympians we will watch during these Tokyo Games, is one where learning, adjusting and practicing skills and techniques is part of a daily regimen. But rest and recovery are requisites that must be built into the daily cycle in order to optimise performance. Sometimes we’ll win, sometimes we won’t. However, by collaborating and supporting each other, we can move beyond playing to win and instead play to thrive.

Susan Goldsworthy is an Affiliate Professor of Leadership and Organisational Change at IMD, co-author of three award-winning books as well as an Olympic swimmer. She is a highly qualified executive coach and is trained in numerous psychometric assessments.

Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff is a historian and author of The Making of Les Bleus: Sport in France 1958-2010. She is a lecturer at New York University and a Research Associate at the Centre for International Studies & Diplomacy, SOAS, University of London.