Is Australia’s coronavirus bill a debt burden future generations must bear?

The Australian government is spending at unprecedented levels with the coronavirus pandemic. Where does this money come from, and can governments keep borrowing – without saddling young people with too much debt?

COVID-19 restrictions have dealt a $17 billion hit to the Australian economy in the past two months. Estimates show Sydney’s lockdown costs more than $1 billion each week, while lockdowns across Victoria have cost at least $5 billion. Given the economic impact of COVID-19, Australia’s debt is forecast to double pre-pandemic levels as the crisis necessitates government spending to spur economic recovery. Government borrowing is a long-term game, and the debt must be honoured one way or another. So how will Commonwealth and state governments pay off this debt?

How much is the Australian government actually in debt?

When the Commonwealth government wants to spend more money than it raises in tax revenue, it must borrow money, and so instructs the Treasury to issue debt in bonds and notes, or Australian Government Securities (AGS). “The government borrows money by issuing bonds – these are financial instruments. So, people ‘lend’ money by buying bonds from the government. The bondholder is then entitled to repayment,” explains Mark Humphrey-Jenner, Associate Professor in Finance at UNSW Business School. “They can sell the bond in the secondary market. Thus, the initial buyer need not be the same as the current holder,” he says.

Any government debt is then typically measured as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP); it is measured not in absolute dollar terms but in comparison to its creditworthiness and ability to repay debts. For example, the 2021-2022 Budget predicts the Commonwealth government’s gross debt for 2020-21 is $829 billion (or 40.2 per cent of GDP). By 30 June 2022, gross debt will rise to $963 billion (or 45.1 per cent of GDP) and then increase to $1.2 billion (50 per cent of GDP) by 30 June 2025.

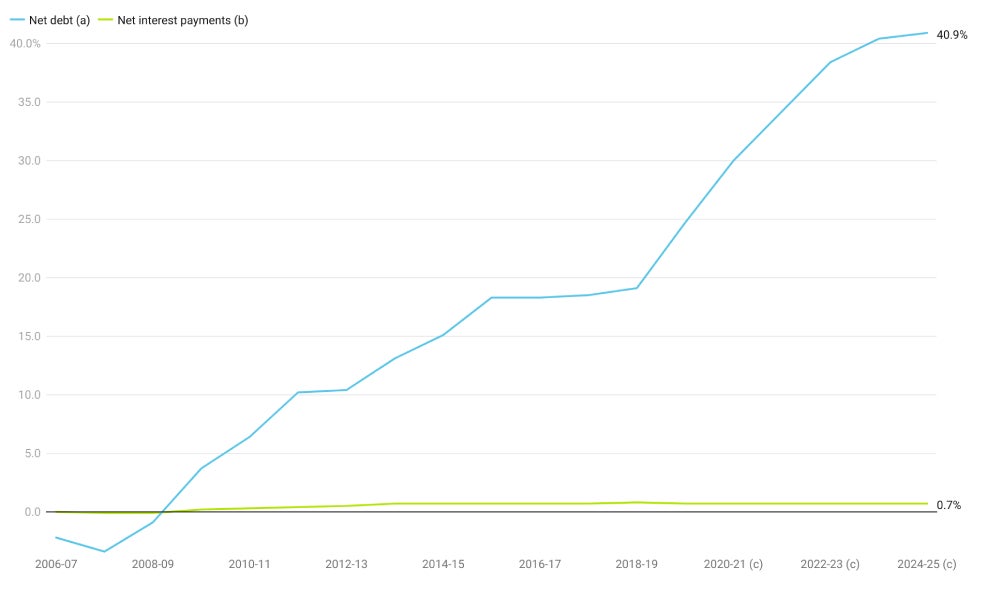

While gross debt gives some indication of Australia’s economic position, the number that is more often reported is net debt, which is the sum of all financial liabilities (gross debt) of a government minus its financial assets. The latest Budget paper shows Australia’s net debt is expected to reach $729 billion (34.2 per cent of GDP) by 30 June 2022 before peaking at $981 billion (40.9 per cent of GDP) in 2024–25. The government also predicts net debt will fall to 37 per cent of GDP by 2032. It’s interesting to note that Australia’s net debt has been steadily rising since before COVID-19, following the Global Financial Crisis, and is not expected to fall below a third of national GDP in the next decade.

Australian Commonwealth net debt and net interest payments (% of GDP)

What states have the most and least debt in 2021?

Commonwealth debt and state debt are very similar as both state and Commonwealth governments are relatively low risk, says A/Prof. Humphrey-Jenner. However, the Commonwealth government has a stronger credit rating and therefore benefits from lower interest rates. Australia’s interest payments (the cost of servicing the debt) are likely to remain flat for some time, at around 1.3 per cent of GDP between 2018-19 and 2023-24. This means the government can borrow at a reasonably ‘low’ price, although it will still cost billions of dollars (servicing Australia’s gross debt has cost $16.7 billion over the past year, for example). So investors who buy state debt can in theory accept a slightly lower credit rating, says A/Prof. Humphrey-Jenner.

States can have different levels of debt for a variety of reasons. “State governments have different debt levels, relative to GDP, in part reflecting how profligate or inefficient their governments are,” says A/Prof. Humphrey-Jenner. “During exceptional times, higher debt might be justified. In which case, we must compare each states’ debt level against the impact of the pandemic. State governments might attempt to tax their way out of debt. But, there is only so high they can go before companies and individuals simply leave.”

In total, the Parliamentary Budget Office projects Australia’s states and territories will owe $371 billion within the next three years. State debt currently accounts for just under a quarter (23 per cent) of total government debt but is expected to hit 29 per cent by 2024, or more than double the long-term average of 13 per cent. NSW’s net debt is forecast to reach $63.3 billion in 2021-22, compared with Victoria's projected net debt of $102.1 billion). By 2024-25, NSW's net debt is expected to reach $103.9 billion, compared with Victoria's estimated net debt of $156.3 billion. This is because, despite ongoing restrictions across NSW, Victoria’s economy has been hit hardest. Also, NSW has the highest GDP of all states, which explains why its debt is likely to be significantly below Victoria.

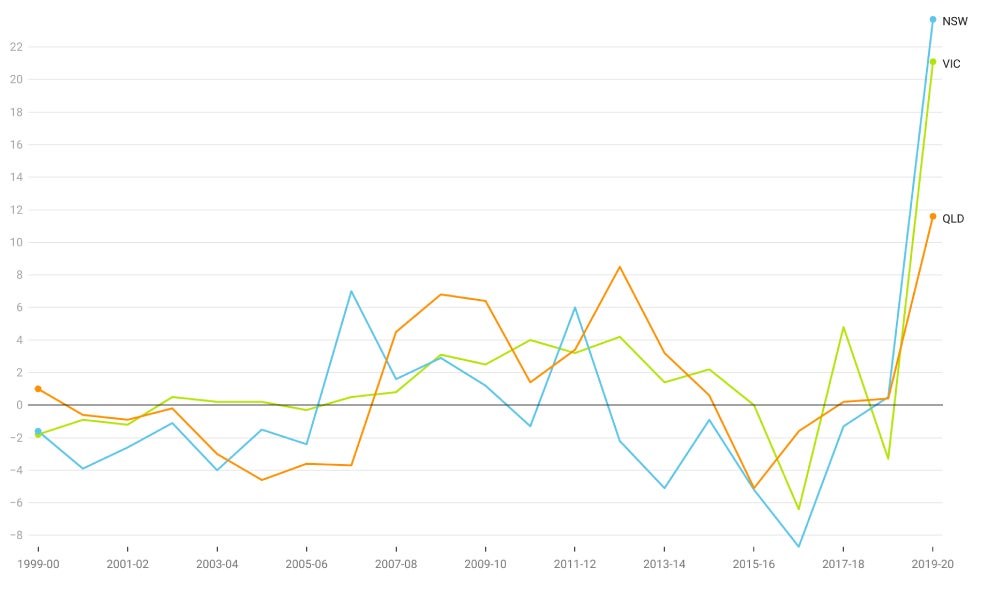

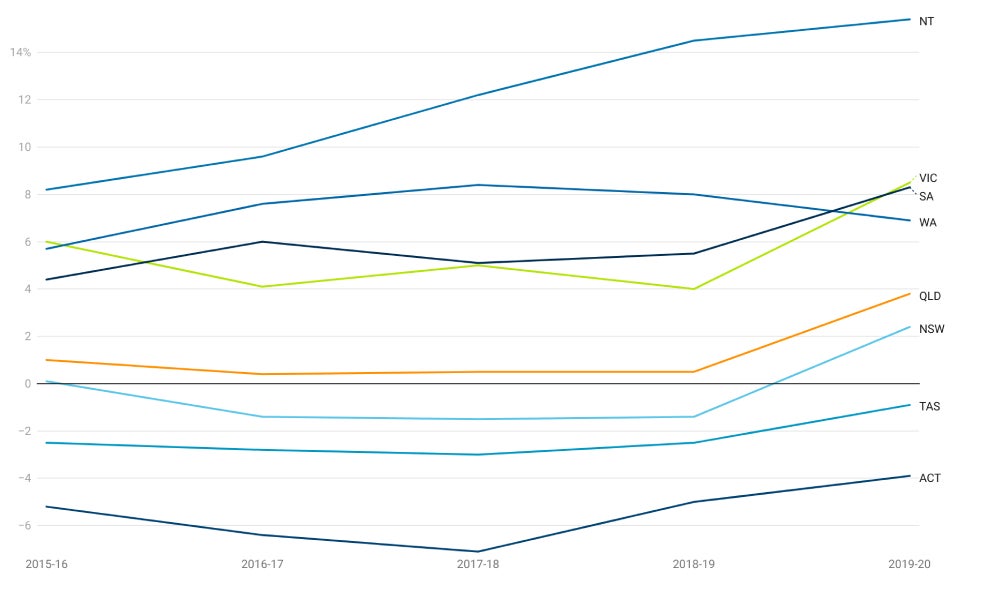

What about the other states and territories? The latest public sector debt analysis by the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows all states increased their debts during 2019-20, except for Western Australia, which decreased by $1.3 billion. Unsurprisingly, the largest annual increases were in New South Wales ($23.7 billion), Victoria ($21.1 billion) and Queensland ($11.6 billion), followed by South Australia ($3 billion), Tasmania ($500 m), and ACT and Northern Territory (at $400m). It’s important to note, however, when looking at graph two, that these numbers take on a different meaning when represented as a percentage of Gross State Product (GSP).

Annual change in state net public sector debt selected states ($b)

State net public sector debt to GSP ratio (%)

Is Australia’s debt sustainable?

Last year, Guy Debelle, Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), gave a speech in November 2020 reassuring the public that there is nothing to worry about. “In Australia, public debt is very manageable. Public sector debt remains low as a share of GDP for the Australian Government … Borrowing costs are likely to remain very low for quite some time, and almost certainly until the economy is considerably stronger. This means that the debt dynamics for the Australian Government and the states and territories are absolutely sustainable,” he said.

Other experts have also pointed out that Australia’s government spending has not been ambitious enough, particularly in terms of spending related to a green recovery given the alarming threat posed by climate change. Others also point out that Australia’s debt levels are also still below its peer countries. “Australia still compares favourably with other major peer nations. Thus, in a relative sense, Australia has also not significantly worsened its position,” says A/Prof. Humphrey-Jenner. Indeed, Australia’s pre-pandemic debt was lower than most comparable countries, and this remains true today. For example, in the US, the national debt is rising at a pace never seen before, with a current US national debt-to-GDP ratio of 127 per cent expected to rise to 277 per cent by 2029. This would put the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio at 277 per cent, surpassing Japan’s current 272 per cent debt-to-GDP ratio.

Read more: Australia’s coronavirus bill: who is the government in debt to?

Nevertheless, he says: “Australia must monitor its debt levels. While the debt levels are not currently a red flag, it is important to be careful. People have unrealistic expectations about how much the government can afford to spend, and the government will need to reign in that spending. Australia’s tax rate is already high relative to competitor countries, so there is little scope to increase government revenue without bleeding talent and companies.” And while interest rates remain low, the interest on this year’s $829 billion gross debt, for example, still amounts to a significant $16.7 billion.

Will Australia ever be called on to pay back the debt?

The lenders from which the Australian Commonwealth borrows include major banks (mainly the big four: Commonwealth, Westpac, ANZ and NAB) fund managers, and foreign central banks. The RBA also buys government bonds, albeit often in the secondary market. In July, the RBA announced it will purchase government bonds at a rate of $4 billion per week until at least 11 November 2021. Compared to last year, it also seems like non-residents hold slightly less government debt than pre-COVID-19, says A/Prof. Humphrey-Jenner. For example, in 2019, non-residents held around 60 per cent of AGS, but this has fallen to around 51 per cent (as at the most recent data point: 31 March 2021), he says.

Bill Whitford, CEO of the Treasury Corporation of Victoria, says that overseas investors account for 10-15 per cent of debt holders. Banks are the largest holders, with around 40 per cent of government debt, and so “the numbers are likely similar across government levels and states,” continues A/Prof. Humphrey-Jenner. But just like Commonwealth debt, it is difficult to know for sure who owns the state debt, because debt often trades in a secondary market, like regular stocks. This means the public doesn't have visibility over all the debt holders. But in general, the largest buyers of all government debt are major banks and fund managers.

According to A/Prof. Humphrey-Jenner, the location of these lenders doesn't really matter. “Lenders cannot simply ‘call’ for their debt to be repaid on a whim. Contracts govern debt repayments,” he explains. Hypothetically, an unfriendly lender might take an aggressive stance if there is a technical default (if the government fails to uphold any aspect of the loan terms, for example). But these lenders don’t have a legal right to simply ‘ask for the money back’, he says. But he notes that were there a call, Australia would likely need to borrow more money from other lenders to pay back the lenders that called for early payment.

Refinancing however is a risk. “If the government relies too much on overseas lenders, it might face risks with refinancing or future borrowing,” he continues. “These risks include: (a) whether the government will be able to find lenders, (b) whether a hostile overseas lender uses debt as an economic weapon by refusing to refinance the debt or continue lending, and (c) whether overseas lenders might force debt terms to change in the future, potentially being unwilling to buy AUD denominated government bonds, and forcing the government to borrow in overseas currency. In turn, this would create foreign exchange risk.”

He concludes: “Lenders cannot force Australia to pay back early, except perhaps if Australia violates a debt covenant. But, even then, such an occurrence would be rare. Thus, even if lenders want their money early, they cannot force Australia to repay early."

The burden of the debt on future generations

There is technically no limit to the amount of debt the Commonwealth or state governments can borrow because in 2013, the debt ceiling, which is the maximum amount of debt that the Treasury can issue to the public or to other federal agencies, was scrapped. But the recent borrowing is causing some to be concerned about whether the debt is too much, and could lead to governments devoting an increasing share of revenue to meet interest expenses and a need to increase taxes, cut spending, sell assets or further increase debt. Others say governments will never have to “pay off” the debt because “it is not debt in the conventional sense of the term”.

A/Prof. Humphrey-Jenner says it is important not to overstate the problem. “While the debt to GDP has ticked up, the increase does not represent an egregious spike,” he says. At the same time, he says that one notable negative is rising state government debt, which has seen a significant spike. “State governments seem to believe they can tax themselves out of debt. Victoria has already shown signs of this, and it is a worrying sign,” he says.

Too much debt means other line items that the government revenue in those future periods would have otherwise funded will be allocated less money, according to Gigi Foster, Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School. “This means less money spent in the future on schools, roads, hospitals, and everything else that we value and that we look to governments to provide (at least in part). So, racking up more debt today implies diminished spending tomorrow on everything else other than paying back the debt. This diminished spending means a lower quality of life for future generations,” she says.

Read more: Should the government worry about its record debt in the federal budget?

On the other hand, Richard Holden, Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School says government debt is both very low and incredibly cheap, and what has been spent so far is crucial to the nation’s economic recovery. And while state governments are a little more constrained than the Commonwealth, he says there are “no problems on the horizon and no need for higher taxes”.

"The notion that we have to 'pay back’ the debt is a complete misnomer. It needs to be serviced, but the principal can be rolled over as it has been in advanced economies like Australia for decades. There’s no magic pudding, but Australia is not fiscally constrained either,” he says. “Look at our response to COVID-19. We spent money which was a smart investment in public health and the economy of the future. Not only could we afford to take the right measures, we couldn’t afford not to."

But what about debt servicing costs, could they become considerably more expensive? For example, if there is a rise in global interest rates driven by increased political tensions in the US, or by the sheer amount of new government debt issued around the world, this could lead to rising interest rates in Australia, therefore increasing debt servicing costs. But even then, Prof. Holden’s past research suggests this doesn’t necessarily have to make Australia’s debt suddenly unsustainable. “The best thing we can do for future generations is not encumber them with a broken economy after COVID. That requires some spending and some debt, but it is very manageable,” he concludes.