Are big tech companies victims of their own success?

The world’s largest technology companies have delivered stellar growth but the good times may prove their eventual undoing, says IMD’s Mike Wade

This article is republished with permission from I by IMD, the knowledge platform of IMD Business School. You may access the original article here.

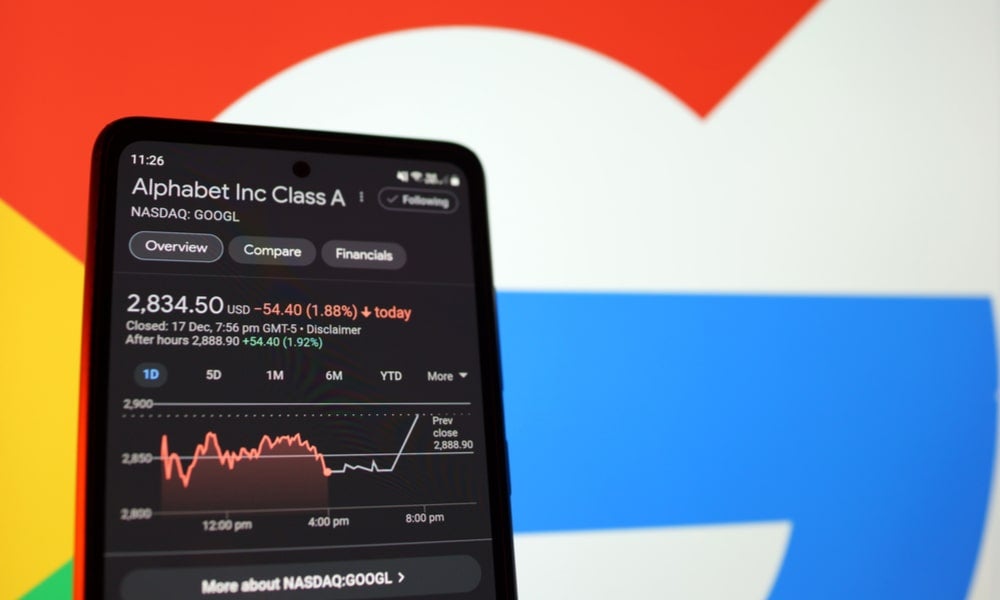

For years, the likes of Meta, Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Apple could do no wrong, commercially speaking; shareholders got rich on a diet of seemingly inexorable growth and share-price appreciation. Today, however, following a period of ruinously poor stock-market performance, investors are feeling decidedly queasy – and are thinking about cutting their losses.

It might be tempting to put the sell-off of tech stocks down to a shift in market mood – to explain it away as an inevitable part of the rotation we have seen from investors from growth to value over the past year. But while this shift in investor sentiment may have played a part in big tech’s slide – Meta shares are down 60 per cent over the course of 20221, with Amazon, Microsoft and Apple share prices falling by 35 per cent, 30 per cent and 25 per cent, respectively – there are also more fundamental issues in play. Most prominent among these is whether these companies have now passed peak growth and are on the downward part of their curve.

Nowhere left to grow

Part of the slowdown is simply owing to the fact that, having gone so fast, they are running out of track. When Google has a 90 per cent share of the internet search market, for example, there isn’t much more upside to grab. With Amazon close to a 40 per cent share in ecommerce in both North America and parts of Europe, the same applies. Apple’s dependence on a single product, the iPhone, leaves it looking vulnerable, given near-saturation of its market.

Evidence is increasing that big tech as a sector is reaching saturation point. Amazon’s quarterly revenue growth in 2022 was its lowest since 2001. Meta’s revenues actually fell, year on year, during the second quarter – the first time the company has ever reported such a decline.

Moreover, while big tech appears to have its many fingers in an ever-increasing number of pies, it is unknown how many of these can deliver a significant ROI. Amazon’s Amazon Web Services cloud computing business is a rare example of successful diversification and Microsoft has both consumer- and business-focused arms. But, overall, there have been more failures than triumphs – and even the wins are unlikely to sustain big tech’s upward trajectory.

Read more: What Meta can learn from the ‘New Coke’ debacle

Another potential pitfall is over-ambition. In particular, the push into healthcare – most recently seen in Amazon’s $3.9 billion deal to buy One Medical – takes big tech companies into a highly regulated area with uncertain returns, which is also well out of their comfort zone in terms of required expertise. Similarly, the metaverse, while exciting, may prove challenging to monetise.

Storm clouds gather

In the meantime, big tech faces rising headwinds. Most obviously, there is the determination of regulators on both sides of the Atlantic to clip their wings.

In the US, Congress is making its first concerted effort since the advent of the internet to regulate big tech. The American Innovation and Choice Act, an antitrust bill, has received bipartisan support in the House and Senate. The bill is intended to prevent platforms from unfairly favouring their own products. It could affect how app stores take payments, for example, and hit cloud service companies trying to cross-sell software and security products.

Separately, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is also flexing its muscles by seeking to block, or at least curtail, Meta’s purchase of virtual reality (VR) fitness start-up Within on the grounds of a monopoly developing in a new industry.

In Europe, meanwhile, the EU in July approved new rules to rein in the power of big tech. The Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act constitute the EU’s cracking down on what it regards as anti-competitive behaviour, forcing Google and Apple, for example, to open up their services and platforms to other businesses.

Regulators aren’t acting only on competition; privacy laws are also impacting big tech. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has significantly limited businesses’ ability to extract value from consumer data. And even where regulators are more lenient, the mood is shifting; Apple’s decision to enable iPhone users to protect their privacy by allowing them to block tracking by apps has sent shockwaves through its market.

For all its exciting innovation, big tech is not invulnerable to policymakers’ “tall poppy” urge to curtail corporate power when it is perceived as growing too strong.

Elsewhere, too, big tech is becoming aware of its mortality. While digital businesses might have expected to avoid supply-chain and logistical issues, it turns out this is not the case. Apple has taken a multibillion-dollar hit to its revenues this year courtesy of a global shortage of semiconductors and the repeated closure of its factories in China, as a result of that country’s “zero-COVID” policy. Amazon, despite its sophisticated inventory-management software, has been caught out by stock shortages, or by simply storing its products in a less advantageous location.

Then there’s the issue of talent. A sevenfold increase over the past 10 years in the workforces of big tech’s five biggest companies – now 2.2 million worldwide – is simply unsustainable amid ongoing skills shortages and labour market issues, as all industries begin to compete aggressively for the top tech talent to ease their digital transformations.

It would be a mistake to overlook the issue of market competition. One irony of the antitrust attention big tech faces is that these companies face more competition than ever before, from one another. In pursuit of diversification, each of the big tech giants is seeking to encroach on the markets of its peers.

Amazon, for example, is investing heavily in advertising, where Alphabet has traditionally been so strong. Alphabet, meanwhile, is determined to grow its cloud business, which is Amazon’s bread and butter. Such competition will inevitably affect margins and market share.

The best is in the past

None of which is to suggest big tech is on the verge of ruin. These are highly profitable businesses that retain dominant shares in their respective markets, which often maintain high barriers to entry. It’s not that decline is inevitable – just that their years of stellar growth may now be behind them.

Nevertheless, they should not expect investors to show much patience. These are businesses that typically offer little in the way of dividend income – and nothing at all in the case of Alphabet, Amazon and Meta. Their shareholder returns must come entirely from growth – and, as that slows, investors will naturally look elsewhere.

This changing of the old guard has become a fact of life for modern corporates. One recent study by the consultant McKinsey found that the average tenure of companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index was 61 years in 1958. Today, it is less than 18 years.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

Big tech itself is partly responsible for that accelerated pace of change. Its disruptive influence and innovative endeavour continue to undermine the prospects of slower-moving, less flexible businesses. The danger, however, is that the tech giants become victims of their own success, trapped by the megalithic structures they have built. More nimble upstarts may now do to them what they have done to previous generations.

Michael R Wade holds the Cisco Chair in Digital Business Transformation and is Director of IMD’s Global Center for Digital Business Transformation. He directs a number of open programs such as Leading Digital Business Transformation, Digital Transformation for Boards, Leading Digital Execution, and the Digital Transformation Sprint. He has written ten books, hundreds of articles, and hosts a popular management podcast.