How Richard Thaler’s insights reshaped economics

Richard Thaler’s research on economics, choice architecture and decision-making has shaped finance, policy and economic strategies, writes UNSW Scientia Professor Richard Holden

Not too many economists – even those with a Nobel Prize – are part of the zeitgeist. But University of Chicago Booth School of Business Professor Richard Thaler is one of them.

He has been dubbed “the father of behavioral economics” by National Public Radio. He’s advised teams in the National Football League on their strategies for drafting rookie players. His insights on how financial markets can veer away from efficiency power the investment strategies of major hedge funds around the world. Oh, and he had a cameo in The Big Short alongside pop star Selena Gomez.

These topics and more were up for discussion when Thaler recently visited UNSW Business School to meet with academics in the School of Economics, supporters and alumni of the university, together with Vice Chancellor Attila Brungs and Dean Frederik Anseel.

From research to impact

Phrases from Thaler’s research – “winner’s curse”, “sunk cost fallacy”, and “nudge” – are part of everyday speech even among non-economists. His bestselling book, Nudge, showed how altering the context in which people make choices can lead to predictable changes in people’s behaviour without banning, mandating, taxing or subsidising choices. This has led governments around the world (including in Australia) to create “behavioural insights” or “nudge” units.

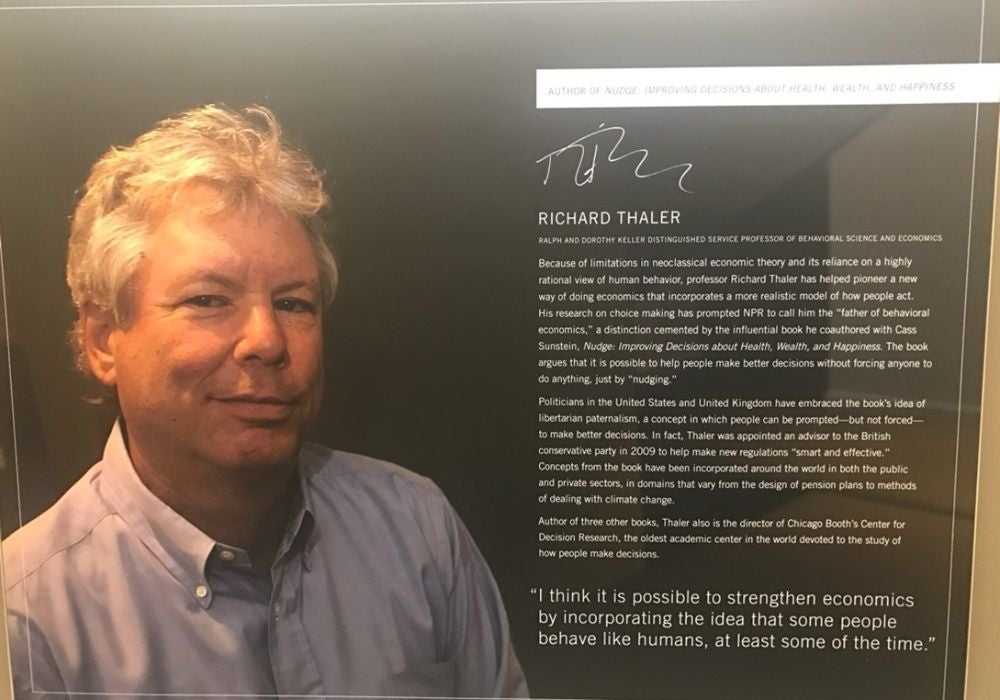

But – as impact usually does – it all began with ideas. Those ideas emanated from a governing thought captured in the poster of Thaler outside classrooms at Chicago Booth: “I think it is possible to strengthen economics by incorporating the idea that some people behave like humans, at least some of the time.” That’s vintage Thaler – witty but also deep.

In one of his early observations, Thaler showed that people systematically deviate from the standard “expected utility theory” of von Neumann and Morgenstern, which is the workhorse economic model of how people make choices. A now classic example is the so-called “endowment effect”:

(a) Assume you have been exposed to a disease which, if contracted, leads to a quick and painless death within a week. The probability you have the disease is 0.001. What is the maximum you would be willing to pay for a cure?

(b) Suppose volunteers would be needed for research on the above disease. All that would be required is that you expose yourself to a 0.001 chance of contracting the disease. What is the minimum you would require to volunteer for this program? (You would not be allowed to purchase the cure.)”

A typical answer from respondents is about $200 for (a) and $10,000 for (b). Yet the standard model says the answer should be precisely the same. People, it seems, are willing to pay a relatively small amount to “buy health” compared to what they require to be paid to “sell health”.

This turns out to be a pervasive phenomenon. Thaler showed it is consistent with people valuing losses and gains differently (“loss aversion”) as in the “Prospect Theory” of previous Laureate Daniel Kahneman and his collaborator Amos Tversky. He showed that firms take advantage of this commercially – they often frame things as “cash discounts” rather than “credit card surcharges”. Moreover, it holds in experiments with real stakes, not simply survey questions. A meta-study showed that in more than 337 estimates in 76 different experiments, the willingness to accept is more than triple the willingness to pay.

Thaler’s concept of “mental accounting” holds that people put expenditures into distinct categories (like food, housing, clothing, etc). This also has strong empirical support and far-reaching implications. When people behave like this, they fail to take advantage of the ability to smooth decisions across categories, and they can behave in ways that are not optimal. One well-documented example is that taxi drivers routinely set a target amount of earnings and stop once they have reached it. This “satisficing” behaviour has broad implications for the labour market generally.

Read more: How AI is changing work and boosting economic productivity

Now, one might think that all these defects in individual decision-making wash out in large markets. Indeed, this was the routine critique of behavioural economics in seminars in the early 2000s. A huge body of scholarship in “behavioural finance” has shown that this is not the case. Psychological factors and limits to arbitrage can have huge implications for the operation of financial markets – creating mispricing and excess volatility.

Thaler also pioneered the concept of “social preferences” where people care about fairness. In an elegant experiment (the “dictator game”) one subject is given $20 and can propose a split with the other subject. If the other accepts that’s what they both get. If they reject, both get nothing. Subjects routinely reject an $18/$2 split – or often even $15/$5 – and prefer to get nothing. This contradicts the standard model and also shows that fairness can be a vital consideration in economic settings.

Finally, the self-control problems Thaler documented in other work mean that individuals can benefit from a kind of “soft paternalism” in everything from quitting smoking to managing their retirement savings. With Nudge co-author Cass Sunstein, Thaler has been the driving force behind designing public policy in a way that recognises and remedies this. Default options in retirement savings are a prime example.

Behavioural insights small and large

A keen golfer who, at the age of 79 still plays off a 16 handicap, Thaler has a specific nudge for golfers. When a player’s ball marker is on the line of a playing partner’s putt, they are typically asked to move it to one side or another. Because this doesn’t happen all that often, it’s easy to forget to move one’s ball back. But failing to do so breaches rule 15.3c and incurs a two-stroke penalty. Even the pros sometimes fall victim to this. Cameron Young, for example, was docked two strokes in the 2023 U.S. PGA Championship.

“I’ve got a good nudge for you,” he tells me, as I am asked to move my ball while we’re playing golf. “Put your ball marker upside down.” It’s brilliant. The other golfers in our group finish out, and it’s my turn to putt after a minute or two. The question is whether I’ll remember to replace my ball. I look at my marker and, it being upside down, immediately remember what I need to do. No penalty. Thaler’s nudge has worked.

Though I definitely appreciated (and needed) it, saving me a couple of strokes isn’t such a big deal. But saving companies from making bad acquisitions is. Thaler has advised companies for years about acquisition strategies. He main tip is disarmingly simple: be careful about winning the deal. This is because of his famous observation – “the winner’s curse”.

In a first price auction with a “common value” component (like what you and I value about a house or firm partly depends on our own tastes, but is partly the same because of intrinsic value or resale considerations) you should “shade” your bid. That is, you should bid less than you otherwise would.

Why? Because you only have an estimate of the common value (e.g. an expert report on the value of mineral rights, a buyer’s agent for a house, a discounted cashflow valuation for an acquisition). The same is true for other bidders. Some expert estimates will be too high, some too low. If you bid what your expert tells you and win, that means your expert had the highest estimate. But the other expert estimates contain information, too. You’re essentially ignoring the hidden information in other expert reports. So, you should shade your bid.

Not doing so is irrational but also highly prevalent, and it explains why so many acquisitions fail, why people overbid for mineral exploration rights, and why people overpay for residential property. There’s a lot more than a two-stroke penalty at stake in these settings.

The biggest open question

On his visit, Thaler was asked: “What’s the biggest question in economics these days?” He’s thought about this. A lot. So, he has a ready answer. “The biggest open question is ‘what makes a choice difficult’?” he fires back.

And he offers a killer example. “We economists smuggle in a lot when we put the ‘max’ operator in front of something. We write ‘max{tic-tac-toe}’ or ‘max{chess}’ and suddenly they’re equivalent. But they’re not. An 8-year-old can solve the former. Magnus Carlsen can’t solve the latter.”

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

Ironically, the problem of what constitutes a hard problem is, actually, a very hard problem. Could the “cognitive turn” in economics – what Harvard economics professor Andrei Shleifer refers to as “getting inside people’s heads” – be the path to an answer? “Maybe”, says Thaler. Indeed he writes in a forthcoming book: “Interestingly, this work has circled back to Herb Simon’s foundational insight that human rationality is bounded by cognitive limitations. No matter how hard we try, we cannot pay attention to everything, remember every event that has ever happened to us (regardless of how minute), or add a long list of numbers in our heads.”

If economists can turn these insights into formal, falsifiable theories, then perhaps an answer to Thaler’s big question is within our grasp.

Richard Holden is Scientia Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, Director of the Manos Innovation Lab in Education, and President Emeritus of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia.