How AI is changing work and boosting economic productivity

AI's economic impact is becoming clearer as businesses report mixed results on productivity, raising questions about its broader effects on labour markets and inequality

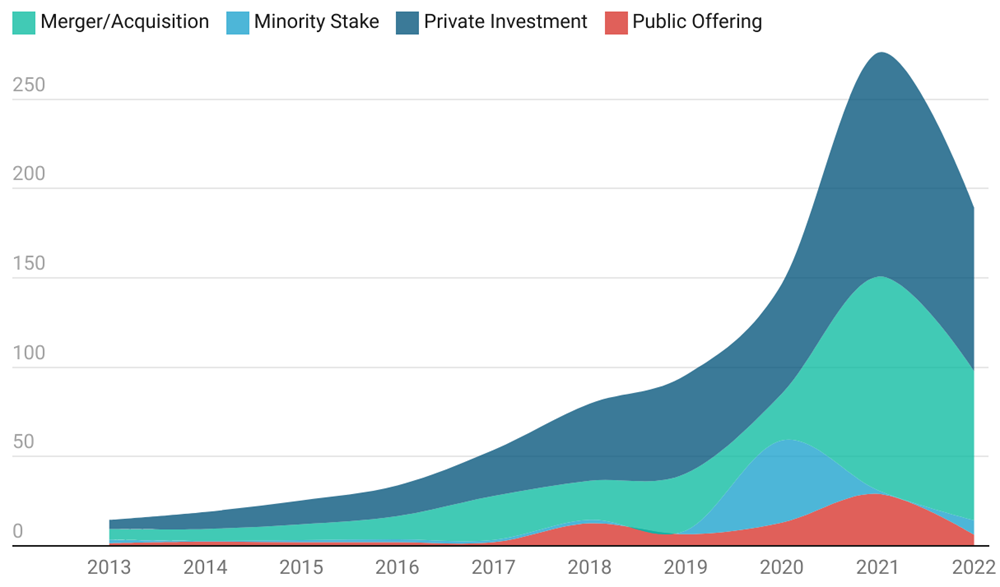

The past year marked a turning point in the evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) and its economic implications. As the dust settled on the initial AI boom, a more pragmatic view of its real-world impact began to emerge. The launch of ChatGPT in late 2022 ignited a frenzy of investment and speculation about AI's potential to revolutionise productivity across industries. Tech giants and venture capitalists poured billions into AI research and development, with AI-related investments increasing thirteenfold, according to the Stanford Institute for Human-Centred Artificial Intelligence.

Global corporate investment in AI

However, as the data above indicates and the end of 2024 looms, the narrative surrounding AI's economic benefits has shifted from unbridled optimism to cautious realism. While early adopters have reported productivity gains, the impact has varied significantly across different sectors and organisations, and the overall economic effect has been more nuanced than initially predicted. As organisations learn from early adopters and overcome implementation challenges, experts believe there will be a gradual but sustained impact on economic productivity in the coming years.

Joshua Gans, Professor of Strategic Management and Jeffrey S. Skoll Chair in Technical Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, said that in analysing the economic impact of AI on productivity, it is important to do so through the lens of prediction and judgement. “AI’s primary advancement is in prediction, which is the ability to use existing information to generate new information, such as predicting weather or classifying images,” he said. “This advancement leads to a significant reduction in the cost of providing quality predictions, which can enhance decision-making against uncertain conditions.”

Quantifying the economic impact of AI on productivity

However, Prof. Gans, who has co-authored two books on the economics of artificial intelligence, believes the economic impact on productivity is not straightforward. While AI can automate tasks and potentially increase productivity, he said the real productivity gains may require re-engineering business processes and integrating AI in a way that complements human judgement. “This is similar to past technological revolutions, such as electricity, which took time to yield productivity dividends as businesses had to redesign their processes to fully leverage the new technology,” he explained.

Daron Acemoglu, Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, takes a more conservative position on the economic productivity benefits of artificial intelligence. “We are told every day by tech leaders and journalists that artificial intelligence is on the verge of transforming everything, including the economy. Large language models and other generative AI tools are predicted to revolutionise productivity and even lead to singularity,” said Prof. Acemoglu, who recently won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Prof. Acemoglu cited bullish forecasts by the likes of Goldman Sachs and the McKinsey Global Institute. Goldman Sachs, for example, initially predicted that artificial intelligence could drive a 7% (about US$7 trillion) increase in global GDP and lift productivity growth by 1.5 percentage points over a 10-year period. Similarly, McKinsey Global Institute has forecast generative AI could add the equivalent of up to US$4.4 trillion annually to the global economy. “Some publications, such as The Economist, are even more bullish. I wasn’t completely convinced by these numbers, so I looked into it myself and wrote a paper on this,” said Prof. Acemoglu.

His paper, The Simple Macroeconomics of AI, suggests a more modest boost in the order of no more than a 0.66% increase in total factor productivity over ten years. He observed that even this estimate could be “exaggerated” as future productivity benefits begin to plateau because early evidence is from tasks that are easier to learn, while some of the future effects will come from harder-to-learn tasks. Consequently, he predicted total factor productivity gains over the next ten years could be less than 0.53%.

While he acknowledges there is a “huge amount of uncertainty” about the future of AI, Prof. Acemoglu is confident that economic gains resulting from AI are “an order of magnitude less than the more grounded applications”. He states: “The bottom line is that current generative AI (plus other expect that AI and computer vision advances) can only perform a small fraction of the tasks in the modern economy.”

Anything that involves manual work, heavy social interaction and/or very high levels of judgment and reasoning cannot be automated, and on this basis, he estimates that less than 5% of the tasks in the US economy can benefit from an AI-enabled productivity boost. “That productivity boost is non-trivial, but not huge,” he said. “On the basis of other people’s work, I estimate that to be about 14%. So, when you combine these numbers, you get something quite small.”

The long-term occupational impacts of AI

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the workplace is fundamentally altering the nature of work and productivity across various sectors. A World Economic Forum report, for example, predicts that by 2027, 69% of companies expect to adopt AI technologies, potentially displacing 83 million jobs while creating 69 million new ones. The report also suggests that the adoption of AI is expected to drive productivity growth, with 75% of companies anticipating AI adoption to create value for their business.

Richard Holden, Professor in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School and President of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, takes a similar line of reasoning in his views about the impact of AI on the world of work. “I think it is going to substitute for some tasks because it’s just going to do some things better than humans can do them,” he said.

“In other areas, it’s going to complement work because it can help people with certain skills to be more effective, more productive, more creative, and more useful. The big questions are: for what set of skills and for what group of workers? Is this going to make their job go away? Is this going to make them better at their job? We don’t really know the answer to that, of course, but there are some hints from what we’ve seen so far.”

Prof. Holden gave the example of the da Vinci surgical robots, which are designed to increase the scale and efficiency of minimally invasive surgery in hospitals. The robots (which have performed more than 14 million procedures) use artificial intelligence and machine learning to provide advanced visualisation features that address stressors facing surgeons, physicians and their supporting healthcare teams.

“da Vinci is one of the leading companies in the surgical robot industry, and some people speculated that this technology will put surgeons out of work. At the very least, that would have been very bad for surgeons,” said Prof. Holden. “It turns out what has happened is that it helps highly skilled surgeons do their job a lot better. But because they were controlling the scalpel, in conjunction with the surgical robot, they were able to make much more accurate incisions and perform all kinds of complicated surgeries far better.”

This also helped with other factors, including recovery times and reducing the risks associated with certain surgeries, and Prof. Holden explained that it has opened the door to some new surgeries that humans couldn’t previously perform. “So actually, it’s made highly skilled surgeons more productive, they can do things that we never thought they could do before, and they can do their existing things faster and better. That’s a good example of technology as a complement to existing skills,” he said.

Prof. Gans echoes Prof. Holden’s observations and provides another example in the form of Tokyo taxi drivers. AI was used to predict passenger demand, which augmented the productivity of drivers by reducing the time spent driving without passengers. Prof. Gans explained that this automation of prediction tasks improved overall job performance, especially for less-skilled drivers, by 14%. “This illustrates how AI can augment human labour by making certain tasks more efficient, rather than replacing human workers entirely. The distinction between augmentation and automation is crucial, as it determines whether AI will complement or substitute human labour in the long term,” he said.

However, Prof. Acemoglu sounds a note of caution about the impact of AI on work – and the broader implications of this change. “Artificial intelligence is not like the weather,” he said. “We shouldn’t think about making predictions as if it has a predetermined path. We choose what to do with any technology, and that is doubly true for AI, which is quite versatile and flexible. The current path is leading us to excessive automation and a very bad data time economy, led by the tech giants.”

However, he said this path is not inevitable. In his work with MIT's Ronald A. Kurtz Professor of Entrepreneurship, Simon Johnson (Nobel Prize laureate and co-author of Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology) and separately with Prof. Johnson and Ford Professor of Economics at MIT, David Autor, Prof. Acemoglu has advocated for “pro-worker AI”. “This would be a very different type of AI technology, prioritising increasing workers’ contribution to productivity,” he explained.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

“It is quite feasible, actually. Most workers are engaged in a series of problem-solving tasks and they do this without proper training and with very limited information. AI is an informational tool, and it can provide better information to plumbers, carpenters, electricians, blue-collar workers, healthcare workers, educators and many others. If we do this, they can become more productive and even more importantly, they can start performing more sophisticated tasks. Such a path for AI will be transformative.”

Lessons from the past in technological developments

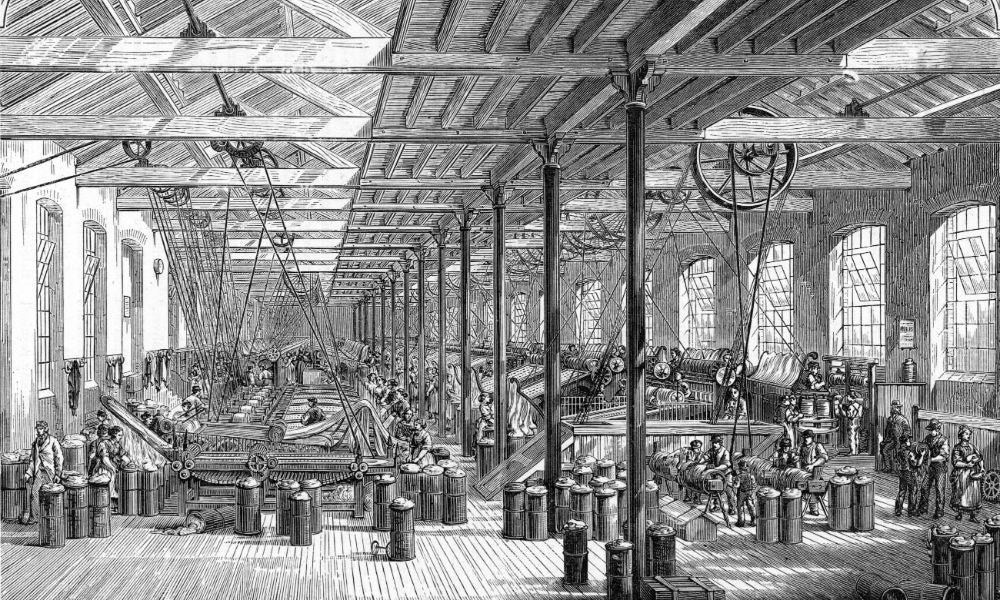

In trying to understand how AI might impact productivity based on past technological revolutions, Prof. Acemoglu said that AI will not suddenly bring “boundless prosperity” to everybody. When he presents research that shows how technologies such as robots and software systems have boosted inequality while failing to deliver expected productivity benefits, he is often asked whether it will be different with AI. “Because I’m told, history shows us that new technologies bring shared prosperity. Unfortunately, this very common view is based on a highly mistaken reading of history,” explained Prof. Acemoglu, who said the British Industrial Revolution was a case in point.

“We are incredibly fortunate, more prosperous, comfortable and healthier today thanks to the process that started in Britain in the middle of the 18th century. But if you read the history properly, you will see that, for the first 100 years, inequality increased significantly, workers were worse off or no better off, and living and health conditions deteriorated significantly. Productivity improvements were slow in coming as well,” he explained.

“It was only in the second half of the 19th century that things changed. Why? Not because there is an automatic process of self-correction from new technologies. History disproves this very clearly. The better direction of technology was very critical and wasn’t automatic. Huge institutional changes that led to democracy and trade unions being recognised were very important and they were fought tooth and nail by the elite. All of this couldn’t be farther from automatic. I think we are seeing the same thing today.”

In trying to understand the future impact of AI based on the technological revolutions of the past, Prof. Holden sees AI as more of an opportunity than a threat. He gives the example of electrification and how this revolutionised the world. “We went from having steam power, which is what was used in industry around the turn of the 20th century. Steam power dissipates a lot of energy, but then electrical power comes into play,” said Prof. Holden, who explained that there are important lessons to be extrapolated from how it led to industrial and organisational change.

Initially, factories relied on steam power, which required a vertical layout near water sources, as the central steam engine dictated the arrangement of workstations. As technology progressed, Prof. Holden said the first change was simply swapping out steam for electricity. This straightforward substitution brought modest efficiency gains of about 20-25% and continued for about two decades.

However, the real breakthrough came later with a complete rethinking of factory design. “People realised that electrical power allowed for a fundamental shift in layout. Instead of building upward around a central power source, factories could spread out horizontally. Electricity could be easily distributed throughout the facility, enabling the use of many smaller, modular power units rather than one large central engine,” he explained. “This reorganisation, sparked by the flexibility of electrical power, revolutionised factory design and operations. It wasn't just a technological change, but a reimagining of how work could be structured and powered, leading to significant improvements in efficiency and productivity. That was the revolution.”

Read more: The strategic impact of AI on business transformation

Prof. Gans is bullish about AI’s potential impact on productivity and predicted that current investments into AI by major investors are likely to lead to different outcomes compared to past technological developments due to several factors. Firstly, he explained that AI is considered a general-purpose technology, similar to electricity (as outlined above) and the internet, which means it has the potential to transform multiple industries and aspects of society.

“This transformative potential is amplified by the significant investments being made, particularly by countries like China, which is spending billions on AI projects, startups, and basic research. Such investments are not only increasing the pace of AI development but also shifting the global leadership in AI research and application, as evidenced by China’s growing share of AI research papers,” he said.

Moreover, Prof. Gans said the strategic implications of AI are profound, as it changes the cost structure of prediction – a fundamental input into decision-making processes. This can lead to new business models and strategies, such as Amazon’s potential shift from a shopping-then-shipping model to a shipping-then-shopping model, which would fundamentally alter consumer interactions and logistics. “Therefore, the outcomes of current AI investments are likely to be different, not only due to the scale and scope of the technology but also because of the strategic shifts it necessitates in business and economic structures,” he said.

Avoiding a dystopian future in the age of AI

As artificial intelligence continues to advance at a rapid pace, concerns about its potential to further drive socioeconomic inequalities have gained traction among researchers, policymakers, and the public. This issue was recently highlighted in the MIT Technology Review, which notes that, without significant intervention, the AI market will only end up rewarding and entrenching the very same companies that reaped the profits of the invasive surveillance business model that has powered the commercial internet – often at the expense of the public.

Many of the best-funded AI companies have been on the receiving end of investments from five companies: Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Salesforce. The power of these companies was recently brought to bear in California, after the government recently made a number of amendments to a bill designed to prevent AI disasters (SB 1047) following pressure from Silicon Valley.

To avoid a dystopian future where AI primarily serves the interests of investors and large tech companies, Prof. Gans said several strategic actions are necessary. First, there must be a focus on creating a regulatory and normative environment that encourages the development of AI applications that are explainable and respect privacy, as these can serve as competitive advantages. “This involves anticipating and shaping the regulatory landscape to ensure AI technologies are developed responsibly and ethically,” he said.

Read more: In the co-pilot's seat: how AI is transforming healthcare

Secondly, Prof. Gans said that addressing the “innovator’s dilemma” is crucial. “Established firms need to be incentivised to adopt disruptive AI technologies quickly, even if it means initially disrupting their existing customer relationships. This can be achieved through fostering competition from new entrants who are not constrained by existing customer bases, thereby encouraging incumbents to innovate,” he said.

Lastly, there is a need for systemic changes in education and workforce training to ensure that the benefits of AI are widely distributed. This includes investing in retraining and reskilling the workforce to meet the demands of AI-driven industries, as he observed the current industrial education system is not equipped to handle this transition. “By addressing these areas, AI can become a foundation for widespread prosperity rather than a tool for consolidating power among a few large entities,” he said.

Prof. Acemoglu pointed again to the Industrial Revolution, when a few factory owners became huge beneficiaries of early technologies and tried to maintain that – even though it was hurting many people. “We are seeing tech giants do the same today. We need a similar fundamental change in both technology and institutions,” he said.

In Power and Progress, for example, he outlined several policies that can be useful for this. “There is no silver bullet, but there are many policies that can be very useful,” said Prof. Acemoglu. “In any case, the most important step is the first one. It has to start with the recognition that it is technically feasible and socially highly beneficial to have a different direction of AI, and that we are not going to get there unless there is proper regulation and government intervention, as well as some democratic oversight and worker voice in where technology is going,” he said.

Prof. Holden pointed to an interesting contradiction in how people view AI. On one hand, he said some fear that AI will become uncontrollable and too powerful to be stopped. On the other hand, these same people worry that a few individuals, like Sam Altman, will control AI and use it to dominate the world. “I find it hard to reconcile these two conflicting ideas. While talented individuals can create AI, they can't control how people use it once it's released,” explained Prof. Holden, who said this is similar to how creators of personal computers or social media became wealthy but don't control the world.

“I am sceptical of both fears about AI – that it will be entirely uncontrollable or that it will allow a few individuals to control everything. It’s not a nature of the technology,” he said.

Practical advice on leveraging AI to boost productivity

While AI has the potential to improve productivity, its benefits are far from guaranteed or uniform, as noted by Prof. Holden. Actual productivity gains are dependent on how businesses integrate AI into their processes, and this integration requires not just technological adoption but also re-engineering of workflows to complement human judgment and skills. This suggests that the true potential of AI lies in how organisations strategically align it with their workforce and business models to drive meaningful productivity enhancements.

“What we currently see in many companies is HR departments rolling out company-wide upskilling programs in generative AI,” said Frederik Anseel, Professor of Management and Dean of UNSW Business School. “There is, of course, value in this. It is valuable for all people to have a basic understanding of how ChatGPT, Co-Pilot and Gemini can help them become more productive and efficient. However, the large productivity gains will probably not come from this incremental approach.”

He echoed the observations of Professors Acemoglu, Gans and Holden, and affirmed that the aggregate of small individual increments in productivity won’t move the needle. So, what should employers be doing then? “With AI, companies should focus on those roles that are strategic differentiators which can provide a competitive advantage. These are the people who need to have the AI skills that possibly allow them to transform the entire business model of a company. If those skills can’t be developed, they’ll need to be acquired,” said Prof. Anseel.

This goes beyond simply hiring people with digital skills, and instead requires detailed workforce planning to introduce AI expertise where it can make a real difference at the company level. This leads to a conundrum for companies, which revolves around designing the organisation to allow those people with AI skills to change the business model. “There is no sense in bringing in costly AI profiles if they then work in a restricted environment where they cannot challenge the boundaries of what they do,” he explained.

“One answer could be to make sure that the organisational architecture allows for these roles to have a free playing field where they can have an impact. It means job crafting, where people shape their roles in a way where the AI skills and products lead them. Obviously, providing such space for innovation and disruption is not something that established large firms are very good at, and thus, that is why we can expect that the major innovations in business AI will come from new start-ups and scale-ups that are not hindered by history and structures,” Prof. Anseel concluded.