AI won't take your job (yet): Insights from OpenAI's Chief Economist

OpenAI's chief economist, Dr Ronnie Chatterji, discusses AI's business impact and how companies can navigate transformation, productivity gains and job market changes

In just two years since ChatGPT burst onto the scene, reaching 100 million users faster than any consumer application in history, artificial intelligence has shifted from a futuristic concept to an everyday business tool. Yet despite this unprecedented adoption and billions in investment pouring into AI companies, most businesses remain caught between two narratives: the promise of revolutionary transformation and the reality of uncertain returns.

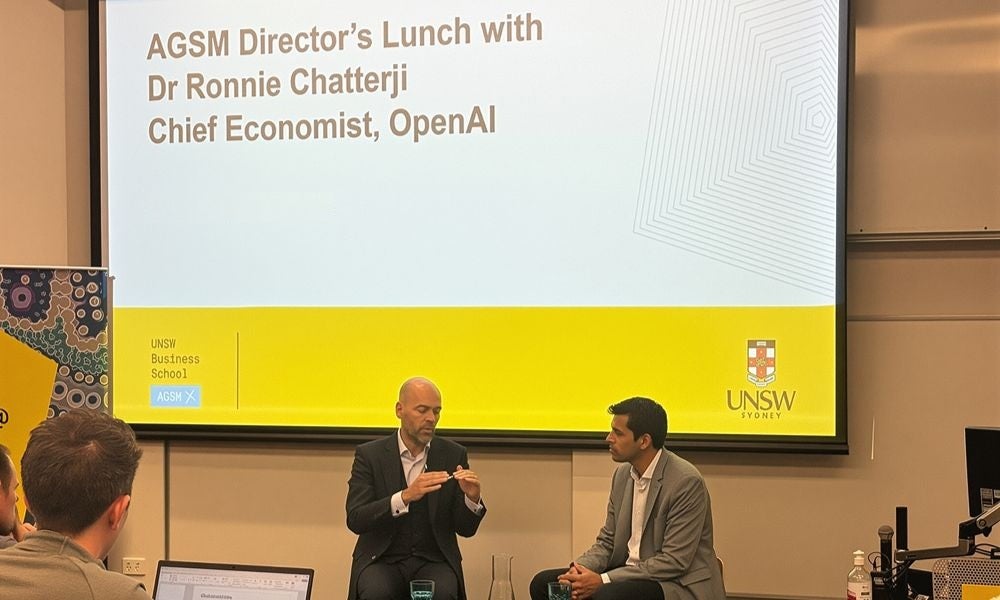

Dr Aaron "Ronnie" Chatterji, OpenAI's first chief economist, recently addressed these issues in a candid conversation with UNSW Business School Dean, Professor Frederik Anseel, for the benefit of AGSM @ UNSW Business School MBA students. Dr Chatterji serves as a Distinguished Professor at the Fuqua School of Business at Duke University, and has also served in senior economic roles under both Obama and Biden administrations before joining OpenAI. He brought a unique perspective on how transformative technologies actually diffuse through economies, and his insights (summarised in the following Q&A) cut through the noise to reveal what's happening with AI in business today.

Prof. Anseel: Where exactly are we in the AI revolution? Are we experiencing genuine transformation or just hype?

Prof. Chatterji: We are in what I call the "in-between times." When you look at technology historically, there's often a significant gap between invention and commercialisation at scale. ChatGPT has become a killer app on the consumer side – we reached 100 million users in about two months without heavy marketing. It was essentially an accidental consumer app. But we're still waiting for the killer apps in enterprise and other areas.

This waiting period isn't unusual. When semiconductors were invented in 1958, it took 10-12 years before they made their way into consumer products. During that time, companies had to worry about cost, build use cases, and identify how people wanted to use the technology. Now, chips are everywhere – they're like the DNA of the built environment.

What's different with AI is the speed of adoption. Despite some people's impatience since 2023, it's actually accelerating quite fast. If you look at the capabilities of what we're doing today versus 2023 and 2024, not just our tools but across the industry, it's pretty amazing. Here in Australia, we're seeing a doubling in weekly active users from last year. As adoption numbers increase, we'll see more killer applications develop, particularly on the business side where the real productivity gains will emerge.

Learn more: How AI is changing work and boosting economic productivity

The business side is really important for Australia's economy. Many people here have worked in different places, but in Australia, the big focus needs to be on how AI can accelerate productivity. I think you're seeing a lot of focus on the enterprise piece of that. I wouldn't be surprised if some of those killer apps emerge in business over the next couple of years.

Prof. Anseel: If AI is a general-purpose technology like electricity, what timeline should businesses expect for real transformation?

Prof. Chatterji: General-purpose technologies, or GPTs, transform entire economies but rarely overnight. At OpenAI, I have access to data on how people actually use ChatGPT across all our users. You can see prompts and the kinds of work they're trying to get done. What I'm seeing is that most people use it as a complement to their existing work, not as a substitute. This is crucial for understanding the job market impact.

Right now, I don't see AI being the reason why there are fewer jobs in tech than before. I think there are other factors at play. But that doesn't mean it won't change. One of my team members from Melbourne does research on the job market to understand whether things are changing, so we can be a reliable source of information for business schools and businesses. Right now, we're not seeing a huge disruption in the market.

For transformation timelines, expect varied speeds across sectors. Highly regulated sectors like healthcare and education will take longer. These sectors employ one out of every seven Americans and have humans in the loop for good reasons – values, culture, and regulatory requirements. Many people think everything's going to happen all at once, and I think that's probably the misnomer. Sectors like healthcare and education, which are highly regulated here in Australia and in the United States, will see their industries and jobs change differently than finance or retail.

I think highly regulated sectors will take longer to adopt AI, and the jobs in those sectors will change differently. That being said, you will see big changes over the next five to ten years. I'm on the lookout for signals, like if consulting firms stop hiring lots of students, which I know is a big interest here. I don't see that happening right now for AI reasons, but if it were to happen, that would signal that changes are happening faster than expected.

Prof. Anseel: Will AI take our jobs? How can we separate real signals from distractions and noise in this debate?

Prof. Chatterji: The conversation around AI and jobs is often framed in the most dramatic terms because those are the narratives that grab attention. Not every headline or study reflects the full picture, but the more sensational angles tend to dominate the debate.

Often, what we see is a new study (that's not very good) that is cited, or a rumour (that's not even true) going viral. I'll click through to the source and think, "Wait, what's going on here?" For example, someone in Sydney told me that some law firms have stopped hiring first-year associates. When we checked the source, it was the opposite – they were increasing hiring. Similarly, I heard private equity firms in the US weren't hiring analysts because AI could do everything. It turns out they're competing more than ever for talent from JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs.

The job market does change for many reasons – tariffs, geopolitics, interest rates, and perhaps AI. But many of the AI job loss stories are written to keep this narrative going.

Learn more: Three key principles for improving visibility through the fog of AI

Now, why might it be different this time? First, adoption rates are really fast. ChatGPT has the fastest growth of any consumer app in history. Second, capabilities are increasing dramatically. If you look at machine learning benchmarks and how quickly it takes us to achieve certain performance levels, that timeline is compressing rapidly. We're 10 times faster in our benchmarks than even a few years ago.

Third, costs are dramatically coming down. The cost of a million tokens has probably decreased by 99% since 2023. So fast adoption, increasing capabilities, and decreasing costs are all happening simultaneously. That's why you have to be humble and say, ‘This time could be different.’ That's what keeps me up at night.

Prof. Anseel: How can organisations ensure we augment roles with AI, rather than job replacement?

Prof. Chatterji: Some of this is our choice, to some extent. As MIT’s Daron Acemoglu (the Nobel Prize winner) says, we can design institutions to govern the diffusion of technology. We can make policy decisions here in Australia and around the world about how firms adopt AI and how it's used, which can affect the pace of transition.

However, in a globally competitive market, some of it's not always up to us. You're all going to work at firms facing global competition. If you're in a jurisdiction where AI adoption is throttled for whatever reason – cultural, legal, or regulatory – and in other countries it's not, that may put you at a disadvantage. Your boss will have to think about whether to adopt things faster.

If this transition happens very quickly, more quickly than we're used to, governments will certainly have to step up. There'll be a lot of pressure on organisations like OpenAI – and honestly, inside the organisation, there's a lot of interest in this. If this does happen, we need to be ready to step up with philanthropic support, training, and other resources. Government is going to play a huge role, which is why I see a key part of my job as informing government leaders with data and evidence. They're going to have to make big decisions down the road if the market changes much faster than before.

The idea that we're unprepared or have never seen disruption is too pessimistic. The scale of the challenge could be bigger this time, and we need to think about it. But governments deal with crisis and disruption frequently, and there's actually deep thought about this on the economic policy side. It's not easy when unemployment shoots up, but we're here today, and the economy has recovered.

Prof. Anseel: Given the massive capital investment in AI compared to current revenues, are we looking at a bubble?

Prof. Chatterji: If Shayne Gary (a Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at UNSW Business School and former visiting scholar at MIT's Sloan School of Management and at Duke University's Fuqua School of Business) and I were teaching a strategy class together, we'd start with cases on Procter & Gamble and General Electric, then get to OpenAI. The challenge would be to apply all the frameworks – Five Forces, SWOT analysis, and capabilities analysis. Then you'd show the numbers: the company is valued at this amount by private investors, but we have so many free users, computing is expensive, and profitability doesn't look like those first two cases during their heyday.

This is a bet by venture capital investors that we'll build such a large user base and develop so many useful tools that this will really change the world of business and create opportunities for us and our partners. The user base is significant, but it doesn't equal profitability yet. If you look at companies like Google and Amazon in their early days and read their financial documents, there was the same conversation – they have all these users, can they monetise it?

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

It's also a bet on the technology's general-purpose nature. This can be used for drug discovery, healthcare research, managing the grid, counselling, mentoring support – all these applications. If we're the foundation model layer with all these apps built on top, look at companies that have played that role through previous tech revolutions. Companies like Nvidia, building infrastructure for AI, are valued where they are for a reason.

The January DeepSeek moment was interesting. There was supposed to be a big comeuppance – people said all the companies investing in data centres and infrastructure were wrong, and we'd see values drop precipitously. Nvidia did drop short-term, and everyone said there's a new narrative in AI. But now, six months later, Nvidia is back to January levels, and our company is still governed by the same idea that compute will be really important, not just for training LLMs but also for inference. The hyperscalers haven't paused their infrastructure investment, much to the surprise of people who read the news in January.

Prof. Anseel: What should MBA students do now to prepare for an AI-transformed future?

Prof. Chatterji: First, take a breath and be kind to yourself. It's challenging when you're graduating from these programs. I taught at Duke long enough to see MBAs during good times with multiple offers and during the financial crisis and COVID, when students, particularly international students, struggled to find opportunities. The luck of when you graduate matters, and that's unfortunate but real. You're not alone in this.

Focus on becoming a better complement to AI rather than a substitute. It's more likely today that somebody who knows AI takes a job, not AI itself. Learning to use the tool is important. People talk about prompt engineering and writing the right prompts, which is good. But my colleague Sandy asked ChatGPT to give her good prompts using its own deep knowledge – that's smart. She doesn't need to memorise prompt structures.

More importantly, how else can you complement AI? I've been learning to code again using ChatGPT. I'm learning something I wouldn't have undertaken on my own. What skills can you learn using AI that you can leverage faster?

Can you build things using AI? Many non-coders are building React apps and other tools with LLMs. Bringing something you've built to an interview – saying "I taught myself classical Greek" or "I built this app" – can impress employers who are still figuring out what AI skills mean.

Be flexible about opportunities. The job that wasn't your first choice two or three years ago might provide interesting opportunities now. The dream job often isn't the first one you get – it's about building skills and working with the right people. I know we all want the best placement out of school, but sometimes taking a job working for the right person and learning new skills matters more.

Main photo credit: Gabriela Hasbun