Stealth tax rises are eating into your income – but we know the solution

To eliminate tax rises stemming from bracket creep, governments need to index income tax thresholds to inflation, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

A curious feature of the Australian tax system is bracket creep. Taxpayers whose income climbs by no more than prices (inflation) get no increase in their living standards. Instead, they see more and more of their income pushed into their highest tax brackets or to even higher tax brackets through tax rises. It means the government’s income from income tax keeps climbing, even if there are no more people paying it and the value of what they earn hasn’t risen.

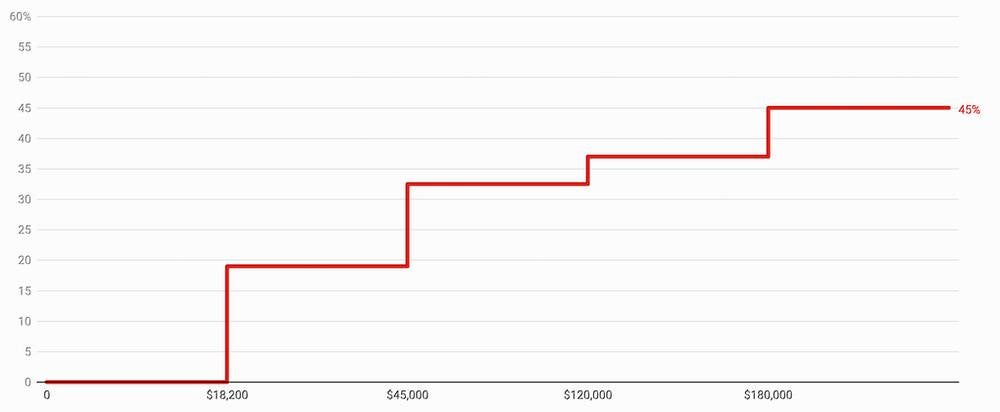

Here’s how it works. The first A$18,200 are tax-free, the rest up to $45,000 are taxed at 19 cents in the dollar, the rest up to $120,000 at 32.5 cents in the dollar, the rest up to $120,000 at 37 cents in the dollar, and anything more than $180,000 is taxed at 45 cents in the dollar.

Australia’s income tax scale

So as someone’s income climbs from, say, $80,000 to $90,000, a greater proportion is taxed at 32.5 per cent, and a lower proportion of it is either taxed less or untaxed.

This happens even if rising prices mean what that person can buy hasn’t changed – or at the moment, with prices climbing faster than wages, means their buying power has shrunk.

Bracket creep is increased tax by stealth

It’s why every few years, the government trumpets a tax cut, which in reality is often no more than giving back some of the proceeds of bracket creep. It could all be ended if the thresholds at which each tax rate cut in were indexed to inflation, climbing each year in line with price increases.

Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser briefly introduced tax indexation in 1976 but abandoned it partially in 1979 and fully in 1982, finding himself not thanked for it.

This week in the Australian Financial Review, economics professor Steven Hamilton made a persuasive case for indexation based on “starving the beast.” As he put it, indexing brackets to inflation at this year’s budget "may be the Liberals’ last chance this decade to put some brakes on the relentless creep of the state and the sapping of hard work and entrepreneurship, having spent a decade enabling it".

This argument has a degree of truth to it, for sure. An ever-expanding government is bound to become lazier and spend money less efficiently than a government that is income constrained.

And it certainly doesn’t suggest that there is no role for government, as is indicated by US anti-tax campaigners such as Grover Norquist, who said: "I don’t want to abolish government. I simply want to reduce it to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub."

But there is also a progressive case for indexation.

The progressive case for indexation

If governments had gone to voters and asked for a tax increase to fund additional spending (for any given budget surplus or deficit), then the link between tax and spending decisions would become clear. If voters wanted more services, such as better hospitals or a better national disability insurance scheme, they would have to vote for higher taxes. Bracket creep means the link is effectively hidden from them, as it shrouds the funding of spending.

It sounds like a subtle shift, but it would be a significant one. Instead of the debate being about “we can get what we want without increasing taxes”, it would become “tax is worthwhile because unless we increase it we won’t get what we want”.

Progressives ought to support the shift. The bottom line is that whatever your politics, there’s a strong case for indexing tax thresholds to inflation. It would make our tax and our political system more honest, ensuring politicians actually acted in our interests.

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub @UNSWBusiness, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative, and President-elect of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. His research expertise includes contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.