Sports analytics: why your favourite team knows more about you than you think

Sports analytics is a burgeoning field that is opening up new opportunities for fan engagement and revenue generation

Each time German football team Bayern Munich plays a home game, the event generates nine million separate pieces of data. There is data about what the players do on field gathered from sensors in their uniforms; data from videos of where the crowd moves to at different times in the event and where the bottlenecks are; data on sales at food and clothing concessions and how the crowds move to them; and data on where the workers and volunteers are at every point in the event.

It’s all used in the growing field of sports analytics, recently examined in Beyond ‘Moneyball’ to Analytics Leadership in Sports: An Ecological Analysis of FC Bayern Munich’s Digital Transformation, a new paper by Felix Tan, a Senior Lecturer in the School of Information Systems and Technology Management at UNSW Business School, and his colleagues Xiao Xiao and Jonas Hedman, both from the Copenhagen Business School.

Sports analytics came to prominence through Michael Lewis’s 2003 book, Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game, and the subsequent film. Lewis traced the true story of how Billy Beane, the general manager of the US Oakland Athletics baseball team, was able to beat teams with more money by using data and statistics to select players. This is the area of sports analytics that most interests sports fans, both in its use for player selection and for improving on-field performance and fitness and injury management.

Supporters as customers

According to Tan, performance and health analytics comprise just one area where sports analytics is used, based on the example of Bayern Munich, a leader in the field. “Sports analytics is not just [about] doing well on the park,” Tan says. “It’s about establishing a platform for people to engage. It’s about ensuring that constituents are able to find value networking with each other through the platform and [that] people can see this ecosystem – and not just in Munich, but people around the world.”

First, there is business analytics. This deals with data analytics related to customers, which in this case are fans and club members. The club has created 80 different ‘roles’ for fans, based on the data it has gathered about them. “On the communication/marketing side, content is then delivered to the fans in a specific form, depending on their defined roles. On the sales side, ‘dialogue steps’ are identified to pinpoint consumers’ decision journey to better inform communication and marketing,” the authors write.

In some respects, the clubs have similar aims to most businesses, but they go beyond that as well. “The revenue for sports is obviously to grow a fan base and get the fans engaged with you, buying your merchandise,” Tan says.

‘The revenue for sports is obviously to grow a fan base and get the fans engaged with you, buying your merchandise’

FELIX TAN

Second, there is event management, using data analytics on match day to ensure the event runs smoothly. For instance, says Tan, on game day by 7.30 pm, 80 per cent of the crowd should already be in the stadium. If that hasn’t happened, then the event organisers will receive an iPad or iPhone alert telling them that, for example, only 75 per cent of people are in the stadium.

The organisers can then change the traffic flow, perhaps opening a boom gate to allow quicker access or putting more staff on ticket sales.

The fan experience

Sports analytics is a growing field, both in Australia and globally. When consultancy firm KPMG introduced the Sports Analytics World Series conference to Australia three years ago, it attracted just 250 attendees. This year’s conference sold out ahead of the event to 1100 people.

Ryan McCumber, a director in KMPG’s global sports analytics team, says US basketball team the Sacramento Kings is a world leader in the use of fan loyalty analytics. The US has largely done away with paper tickets and instead uses smartphone apps, which is where the better experience for fans begins. When they buy a ticket, they can see where they’re going to sit and look at the actual view they will have, and, for instance, whether it’s likely to be a sunny day and if they will be in direct sunlight, McCumber says.

Once the fans arrive at the stadium, analytics can do a lot more. The event organisers can see in real time how food and beverages are selling. “Let’s say the game is about to end, or we’re heading to the third quarter of a basketball game and they haven’t sold a lot of tacos,” says McCumber.

“They can take a certain subset of the fans based on customer attributes and send them a discount – you know, 25 per cent off tacos – or they could put it up on the big jumbotron for the whole stadium. They get fans involved and say, ‘If the team scores a three-pointer, or if the team is winning at the end of the third quarter, everybody gets a free taco, or everybody gets 25 per cent off a taco’.”

And because they have all sorts of data on every ticket holder in the stadium, they could target a particular demographic.

In fact, they can target individuals. McCumber watched a live demonstration of the technology from the KPMG office in Sydney while a game was taking place in Sacramento. The event managers noticed popcorn wasn’t selling in a particular part of the stadium. They picked out one seat and sent the person a voucher for free popcorn via the mobile app.

‘They can take a certain subset of the fans based on customer attributes and send them a discount’

RYAN MCCUMBER

“Pretty soon, we saw the guy get out of the seat, we saw him go and purchase his popcorn,” McCumber says. “Twenty minutes later, 10 more people around him bought popcorn because they saw the popcorn.” They can drive engagement through loyalty schemes, for purchases, but also for things such as voting on the player of the match after the game.

Added capabilities

These are all examples of what McCumber calls stadium and fan loyalty and sponsorship analytics, and it’s an area where Australia lags behind.

It is possible in the US, because sports teams often own the stadium where they play, and so have an interest in investing in better customer experience (for instance, most Australian stadiums have poor mobile wi-fi which is needed for so many applications) and have an interest in ensuring the food and merchandise concessions also do well.

“It’s a disjointed ecosystem in Australia,” McCumber says. However, there are signs of change. The AFL owns Etihad Stadium in Melbourne and is interested in analytics, and many of the new franchises that are hoping to join the National Soccer League have proposed building their own stadiums, suggesting they could also add these capabilities.

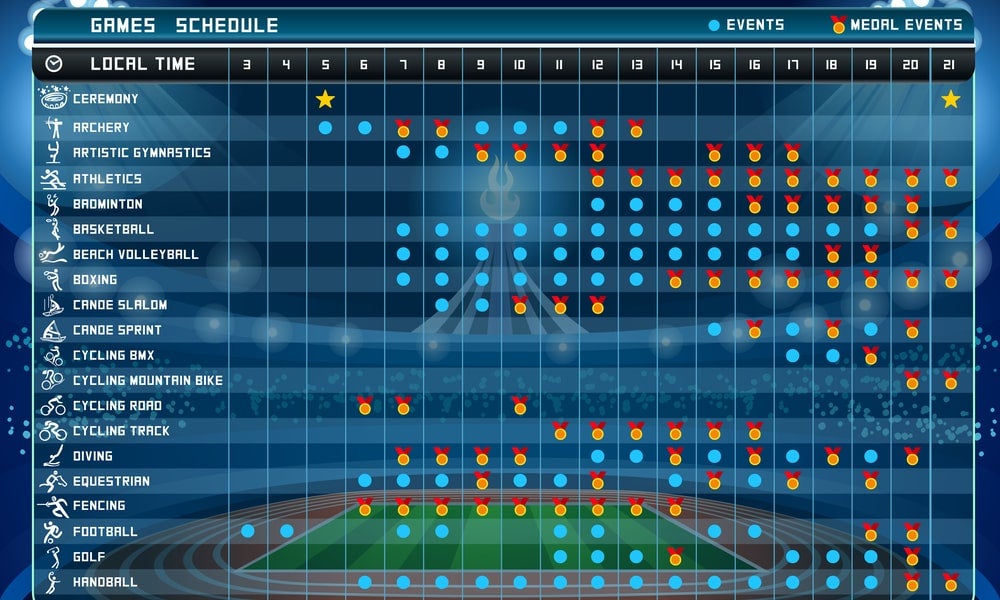

Another area of sports where analytics plays a major role is in match scheduling, which is McCumber’s particular area of expertise. McCumber and KPMG started doing the scheduling for the US National Basketball League two years ago, taking over a process that used to be done by hand.

In deciding when matches take place, they have to take into account how much time to give players between games to recover, how much travelling they have to do, which games and teams rate well on television and when, what likely gate takings will be for a particular date, and stadium availability, to name just a few. In fact, there are around 1000 constraints on when games can take place.

The problem is solved with analytics, via a program that can run 200 million alternative schedules a minute, ultimately looking at 35 trillion different schedules to determine the optimum outcome. In this area, Australian sports are not so far behind, and are starting to adopt the technology.

For more information read Beyond ‘Moneyball’ to Analytics Leadership in Sports: An Ecological Analysis of FC Bayern Munich’s Digital Transformation or please contact Felix Tan directly.