Why Rishi Sunak has his work cut out for him

Rishi Sunak has inherited a mess and it will be a tough challenge to restore the UK’s economic credibility, writes UNSW Business School’s Mark-Humphery Jenner

Rishi Sunak is the third prime minister in 2022. Following Boris Johnson’s scandal-plagued resignation, Liz Truss assumed the Prime Ministership. However, her program of tax cuts and spending increases triggered a market rout, an embarrassing capitulation, and her resignation. The timeline of events looked like this:

- Liz Truss becomes PM on a platform of unlimited energy subsidies and tax cuts

- On this program, and the mini-budget, bond yields increase on concerns about how the government would pay for this program.

- Prices for existing bonds plummet. This is because the old bonds pay an interest rate below what the new risk level warrants.

- Bond prices plummeting creates a crisis for pension funds and other fund managers. Many pension funds had bought bonds on leverage. The lower prices raised capital adequacy concerns.

- The Bank of England intervenes to buy government bonds to lower bond yields and prevent pension funds from collapsing. This resembles quantitative easing, but here it was for financial stability reasons.

- Liz Truss reversed the tax cut policy and pared back the energy support. The chancellor (Kwasi Kwarteng) was replaced.

- Liz Truss resigns, becoming the shortest-serving Prime Minister in British history.

With the chaos surrounding Rishi Sunak’s rise, it begs the question of how exactly the market reacted and what he still has left to do.

How did the markets react?

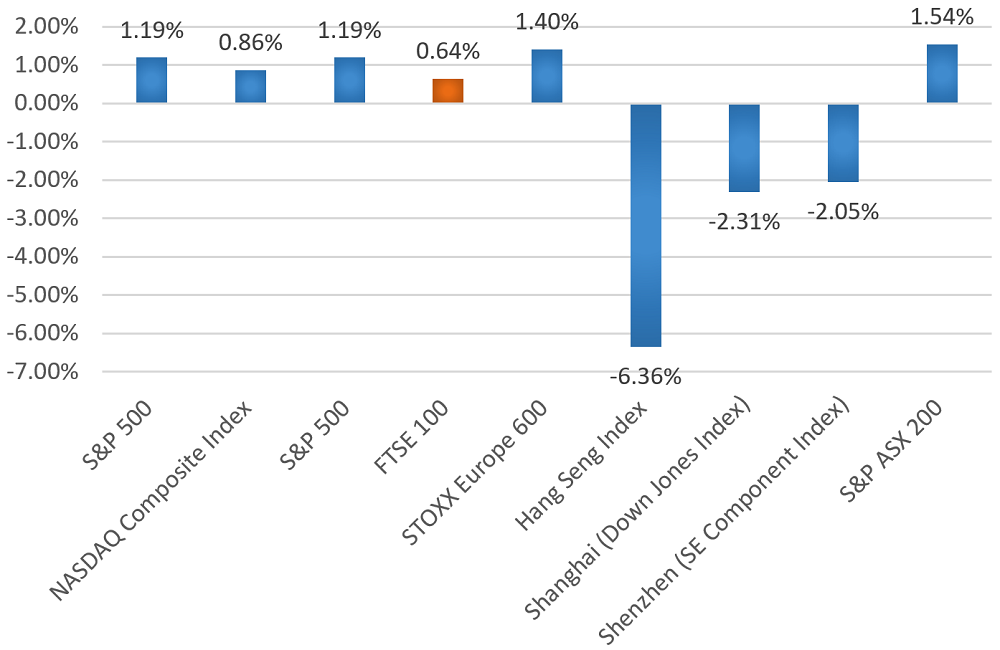

A good starting point is to look at how the markets reacted. After all, if the economy tanks, then so do markets. On becoming PM, the UK index – the FTSE 100 rose a modest 0.64 per cent, well below the broader European STOXX 600. But, this was stronger than both the S&P500 and the NASDAQ composite.

Interpreting the market’s reaction is fraught here, however. The market likely already anticipated Sunak becoming PM. Thus, since only ‘new news moves markets’, this would already be factored in. Further, events in China also impacted markets: Earlier in the day, the Hang Seng fell by more than 6 per cent and both the Shanghai and Shenzhen indexes fell by more than 2 per cent. This could have created some negative overflow into the UK market.

Bonds also reacted favorably. Government yields fell slightly on Sunak becoming PM, with the two-year yield falling by around 25 basis points.

This altogether suggests a lukewarm reaction to Rishi Sunak becoming PM.

Why the tepid response?

There are several good reasons for the market to be cautious. These are in addition to the fact that Sunak was expected to win the leadership contest and the contemporaneous global financial news.

Sunak’s policies are not universally well-liked. When he was Chancellor, Sunak retained the cap on bankers’ bonuses. It fell to Liz Truss to remove the cap. The cap was bad policy. It did not raise government revenue. Indeed, the government forewent tax revenue it could have earned on those bonuses. Further, incentive compensation is a well-established way to encourage better performance.

Sunak has also indicated that he is open to higher taxes. He moved to increase the UK corporate tax rate. He is also opposed to reducing personal tax rates. In the current budgetary situation, he has little choice. Indeed, Liz Truss’s policies triggered market chaos, and a reversal of her planned tax cuts. However, part of the issue with Liz Truss’s policies was cutting tax and increasing expenditure simultaneously. This was especially so given the dearth of modeling and communication surrounding her measures. Further, tax hikes are extremely unpopular with the party members. And, holding the party together will be difficult under tax increases.

Read more: How likely is a US recession? About 75 per cent

Sunak will need to confront the issue that the UK increasingly needs human and financial capital, and must increase productivity. Brexit has made this even more prescient. Brexit has removed the UK from the common market. This limits the free flow of human capital between the EU and the UK. Brexiteers naively, or duplicitously, depicted immigration as low-skilled and ran the hackneyed line that immigrants were taking citizens’ jobs. But, the free flow of capital allowed talent to freely move to the UK to pursue entrepreneurship or other growth-generating fields. The UK Office of Budget Responsibility states that Brexit will reduce migration to the UK. Brexit has also reduced UK GDP growth due to trade concerns.

The problem is then how to solve this. The UK needs growth. And it can generate growth internally and/or with externally derived labor and capital. The UK must then make itself a more attractive place for capital and talent. But, it is competing with the US (amongst other places). The US has significantly lower tax rates. The US corporate tax rate is 21 per cent (cf the new UK rate of 25 per cent) and the top federal tax rate of 37 per cent only applies to people earning more than $US539,900. Thus, in a world where the UK needs talent and capital, it will simply struggle under Sunak’s policies.

The talk of windfall taxes also spooks markets. Versions of this came in under Sunak. Windfall taxes send bad incentives. They tell companies that if they are successful then they will be hit in good times, even if those good times are necessary to offset the years of losses. This is even more so since oil prices were below $20 in early 2020. And, oil prices above $100 are not abnormal. This especially applies to renewables generators. It sends a perverse incentive: capital will hardly flow to bring more renewables online in the presence of windfall taxes on it.

After the current market chaos resolves, Sunak will need a cohesive plan to generate long-term growth. At present, the UK lacks one. Australia faces similar issues, albeit without the accelerant of Brexit and with the buffer of natural resources.

What does Rishi Sunak mean for Australia?

Could Rishi Sunak present a silver lining for Australia? Could there be growth opportunities for the Australian economy?

The UK and Australia had agreed upon a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). This must still pass parliament. It has also been controversial, with concerns ranging from its ‘limited economic effect’ through to its impact on UK agriculture. However, given that Sunak has relatively few growth opportunities – and is running on a platform of fiscal ‘responsibility’ or ‘stability’, it is logical that he could further push for the FTA’s consummation.

Read more: Contagion effect: How financial crises spread across borders

Does Sunak’s rise imply anything about Australian policy?

Sunak Came to power due to chaos following Truss’s decision to both cut taxes and increase spending. It is sometimes remarked that this has implications for Australia’s stage three tax cuts. It does not. The two policies are distinguishable for multiple reasons.

On the revenue side: the UK’s top marginal tax rate is 45 per cent. Australia’s is effectively 47 per cent: the marginal rate of 45 per cent plus a Medicare levy of 2 per cent. The UK’s rate applies to earnings over £150,000 ($A268,175). By contrast, Australia’s rate applies to earnings over $A180,000. Thus, the UK already has significantly lower tax rates than does Australia. Further, that notwithstanding, the stage three tax cuts only change tax brackets. They do not lower the marginal tax rate. This makes them markedly different from Truss’s plan to reduce the top rate to 40 per cent. Australia’s stage three tax cuts also do not take effect yet, and will likely only do so after inflation has ameliorated. Thus, the proposed UK policies were entirely different from Australia’s stage three tax cuts and there is no analogy.

On the expenditure side, there are some lessons. Australia has issues with the magnitude of the NDIS. The UK has found that it cannot have uncapped expenditure: this was a fundamental issue with Truss’ energy subsidies. Australia must learn from this and take coherent steps to restrain the NDIS and similar programs lest they create a large structural deficit.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

Increased taxes cannot solve that deficit. As indicated above the US’s top federal rate is 37 per cent, applying to earnings over $US500,000. In Australia, the top tax rate is 47 per cent, applying to earnings over $A180,000. This creates significant issues attracting talent and financial capital. Australia must consider the competitive environment for talent and capital when designing policies.

Where then does this leave us?

Sunak has inherited a mess. The UK faces significant economic headwinds. He now has the unenviable task of trying to demonstrate fiscal ‘responsibility’ while ensuring the UK is competitive and can increase growth. In the short-to-medium term, this can benefit countries such as Australia with a push towards free trade agreements. However, given the UK’s parlous economic situation, the size of the UK export market requires sober consideration.

Mark Humphery-Jenner is an Associate Professor in the School of Banking & Finance at UNSW Business School. He has been published in leading management journals and his research interests include corporate finance, venture capital and law. For more information please contact A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner directly.