The Productivity Commission needs to put dynamism back into the economy

The Productivity Commission’s draft report misses a key driver of productivity growth – how firms grow, adapt and exit in the economy, writes UNSW Business School's Petr Sedláček

The Productivity Commission recently released its draft set of recommendations for the government on Creating a more dynamic and resilient economy. What is noticeably missing from the analysis, however, is business dynamism itself.

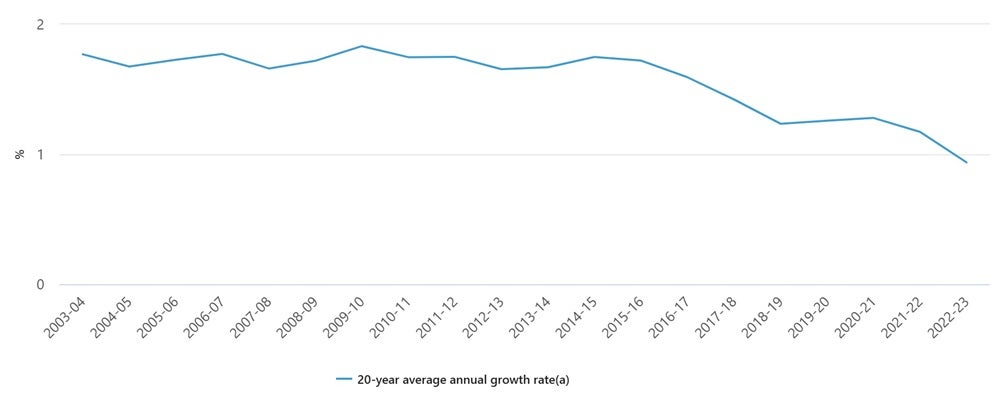

First, let’s make clear why having an inquiry into economic dynamism is important to begin with. Working smarter, not harder, is the typical one-liner for explaining what productivity is. As has been hammered into anyone who has listened, watched or read the news in the past few months, productivity growth is key for ensuring that Australian living standards keep on improving.

Labour productivity growth

How productivity relates to business dynamism

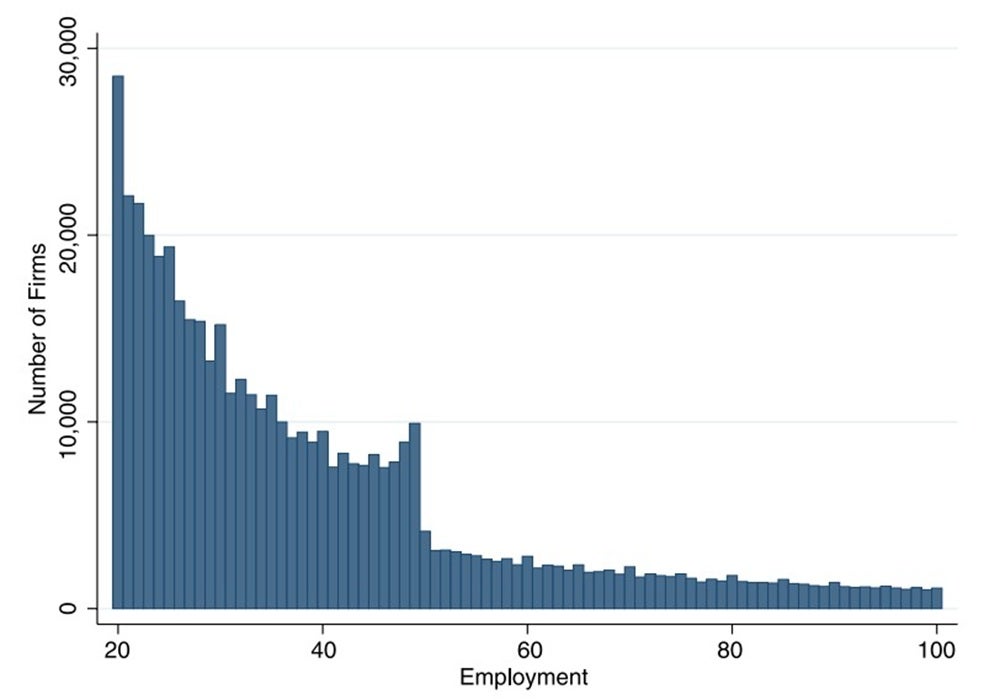

What may come as a surprise, though, is how very different firms are when it comes to working smarter. According to Treasury estimates, the top 25% of the most productive firms are somewhere between 3-5 times more productive than businesses in the bottom 25%. If you stretch this comparison out to the top and bottom 10%, the figure balloons to something between 10 to 12 times as productive. Moreover, these are not comparisons across different sectors. No, they compare apples with apples by computing productivity differences within narrow industries – think, for instance, “ready-mixed concrete manufacturing”.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could move resources, like finances, capital or workers, from the least productive firms to those at the top of the productivity ladder? Presumably, they could use them much more efficiently (the definition of working smarter, not harder) – just for different employers.

This is precisely what “business dynamism” does. The entry of new firms, the growth of the successful (especially younger) ones, the movement of workers across employers, and the exit of less efficient businesses all help reallocate resources to more productive uses. Unfortunately, the pace of business dynamism has been on a steady decline. Hence, the inquiry into how to kickstart it again.

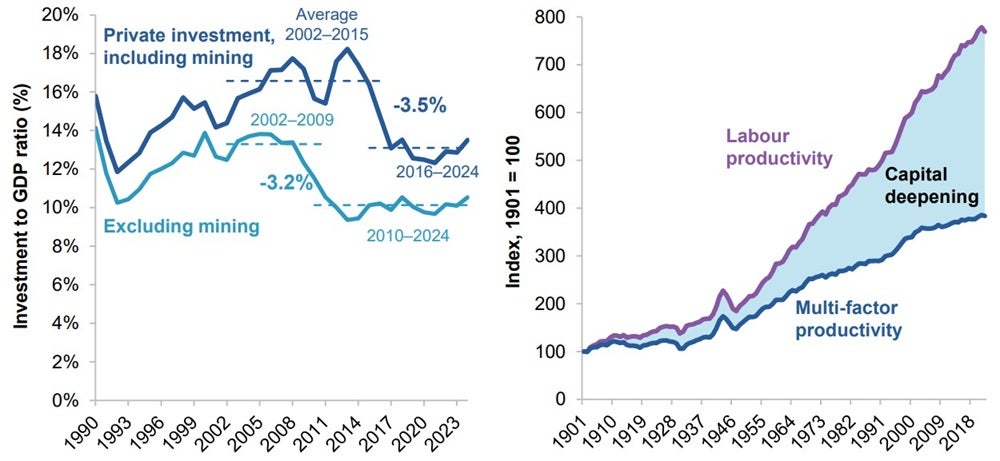

Private investment is falling but it’s not the full picture

Now, back to the Productivity Commission’s report. Don’t get me wrong, private investment – which, just like business dynamism, has been on a steady decline for years – is a crucial driver of productivity growth.

Investment is down, and therefore capital deepening is down

It’s reasonable to propose to use tax cuts (for most firms) to motivate businesses to start investing again. Similarly, it makes sense to develop a framework which streamlines regulation and acknowledges that – like everything in life – also regulation comes with costs and benefits.

Predictably, however, the Productivity Commission’s recommendations didn’t land without controversy. Especially the suggestion that tax cuts are funded by large businesses (those with over a billion in revenue) kicked up some dust.

Part of the issue is that the devil is always in the details. And the Productivity Commission’s modelling choices may be missing an important chapter in the story. Specifically, in the 92-page report, “new entrants” are featured 8 times, “exiting firms” twice and “young businesses” get one honourable mention. Reallocation of resources isn’t mentioned at all. In short, business dynamism doesn’t play a key role in the analysis.

Are tax incentives enough to encourage firm entry and growth?

This also means that some key questions remain untouched. For instance, will the proposed tax changes help motivate new startups to give it a crack, which they otherwise wouldn’t have done? If so, will these new startups be ambitious, invest, innovate, create jobs, and eventually grow to become large firms?

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

Or will Australia end up with a larger chunk of less productive businesses, which, under the more favourable tax conditions, are capable of just scraping by? Will aspiring large firms also be motivated to invest more and grow further? Or will they try to avoid the one billion threshold? If so, what will such cautiousness of large players mean for overall investment?

Of course, not everything could have made it into the `interim’ report. The Productivity Commission is actively seeking more input into its recommendations and aims to include further modelling in its `final’ reports. The commission is also well aware of some concerns. For instance, it acknowledges that “the use of a threshold risks distorting private sector decisions about company structure."

The need for models that capture firm-level reallocation

What is missing, however, is an attempt to quantify such concerns. The Productivity Commission could lean on existing research about how tax cuts and immediate investment expensing spur firm entry or how size-dependent regulation hampers business dynamism.

It could also contemplate broadening its modelling arsenal to include macroeconomic models that explicitly take business dynamism into account. By now, these frameworks have been successfully applied to understand a range of important questions, including long-run productivity growth or the macroeconomic impact of market power.

In the end, the Productivity Commission's recommendations may be hitting the right nail on the head. It is applaudable that the analysis is based on BLADE – a dataset with a cool name and extremely detailed information on Australian businesses. But details of the proposed policies will matter.

The Productivity Commission’s reports may be even more impactful if they put dynamism back into a more dynamic and resilient economy.

Petr Sedláček is a Professor in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School, a Future Fellow at the Australian Research Council and Associate Member of the University of Oxford.