Why is a ‘positive duty’ to prevent workplace sexual harassment so important?

The Morrison government says existing laws already provide a positive duty to prevent sexual harassment but do they go far enough?

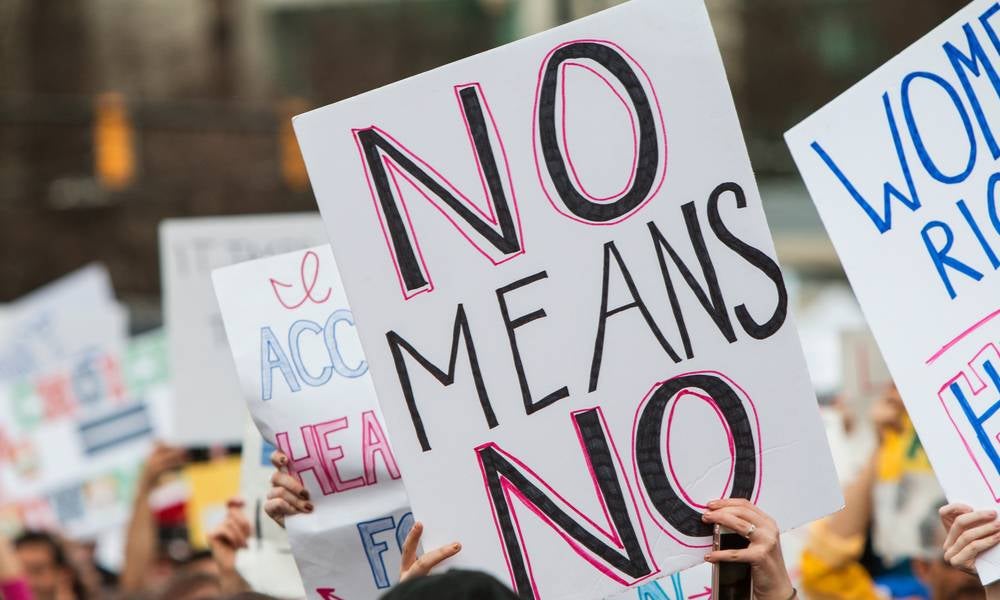

Recently, the national women’s safety summit was roundly criticised by community and women’s groups as being little more than a talkfest. It was intended to inform the development of a national plan to prevent violence against women and their children. But the government’s recent steps on this issue show how it is more committed to rhetoric and spin than taking real action.

Earlier in the month, the parliament passed six amendments to the Sex Discrimination Act out of the 12 recommended in Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins’s Respect@Work report. The report contained a total of 55 recommendations, not all of which require legislative amendments to be implemented. But the government was also heavily criticised for not implementing all of the recommendations. One of the most important was Jenkins’s call to introduce a positive duty on employers to prevent sexual harassment.

Sam Mostyn, the president of Chief Executive Women, said on ABC Radio National: "Once you make it a duty, employers pay attention and know that there is a consequence for failing to provide that environment. … The amendment is simple, it’s well-supported and it’s one of the clearest ways to say, ‘when women feel safe at work, they want to keep working’."

What is a 'positive duty'?

A positive duty requires organisations to be proactive in addressing the disadvantages and discrimination women experience at the workplace in order to promote equality. The federal government has been hesitant to enact this, saying it believes existing workplace health and safety laws already provide a positive duty to prevent sexual harassment.

According to the Respect@Work report, a positive duty does exist in workplace health and safety laws to eliminate or manage hazards and risks to a worker’s health, which includes psychological health and therefore sexual harassment. However, this duty does not go far enough and is not explicit enough in referring to sexual harassment. Affirmative action legislation also does not go far enough to ensure gender equality. The Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 requires employers with more than 100 staff to implement measures to advance gender equality and report on progress.

But affirmative action only requires employers to undertake the minimum amount of effort on this front. Researchers have noted that fulfilling the reporting requirements is seen by many employers to be a bureaucratic and compliance exercise, which does not necessarily translate into action.

Read more: Why the government's plan for dealing with sexual harassment in the workplace falls short

A positive duty, by contrast, imposes a higher obligation. It requires employers to actively promote gender equality and can include going beyond the workplace to take action in the community. This is why Jenkins recommended a new positive duty specifically focused on gender equality. It would build on our existing workplace health and safety laws by requiring agencies to do more than just meet benchmarks.

It would also complement the existing Sex Discrimination Act by taking a proactive and collective approach to ensure gender equality, rather than relying on individual remedies to prevent discrimination.

What does this look like in practice?

One of the main ways a positive duty on gender equality can be implemented is through “gender mainstreaming”. This means casting a gender lens over all organisational policies and practices to determine how they treat women. This might reveal, for example, that some human resource recruitment and selection processes are disadvantaging women. By being proactive, organisations can take steps to change these processes.

Arguably, a positive duty would extend to advancing gender equality in the workplace more broadly and creating the type of workplace environment that is incompatible with sexual harassment and discrimination. This could include, for example, an assessment of workplace culture to identify barriers preventing the full participation of all genders in formal and informal workplace practices, and then taking actions to remove those barriers. Jenkins’s report also recommends strengthening.

Are there good models to follow elsewhere?

This is not a new phenomenon in Australia; in fact, a positive duty to prevent sex discrimination already exists in Victoria. In 2020, the state government passed the Gender Equality Act, which requires employers to take positive measures to progress gender equality. The law has robust compliance mechanisms. Public sector agencies are required to develop, implement and report on their gender equality plans. Sanctions range from a light touch (being “named and shamed”) to a heavier hand (taking appropriate action against non-compliant organisations).

Victoria’s act is based on laws from overseas. Positive duties on gender equality were initially implemented in the UK public service in 2011. These duties have had an impact beyond the public sector, as well, with ideas and strategies on equality now being incorporated by many employers in the private sector.

However, some researchers argue the impact of the UK gender equality duty has been tempered due to weak enforcement measures and a focus on process rather than outcomes. These researchers have recommended strengthening the UK positive duty by collecting better data on women’s workforce participation, improving workplace education and leadership on gender equality issues, and bringing in stronger enforcement mechanisms for non-compliant employers.

The positive duty put forward in the Respect@Work report would have incorporated these elements. Jenkins sounded a warning back in April that not implementing a positive duty would be a “missed opportunity”. This warning, however, went unheeded by the government with its reforms. Prime Minister Scott Morrison has said: "the only way we end violence is to focus our efforts to prevent it from happening in the first place." But not reforming the law to introduce a positive duty signals a failure and lack of political will to prevent violence against women and advance gender equality.

Dr Sue Williamson is a Senior Lecturer, Human Resource Management in the School of Business at UNSW, Canberra. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.