How credit supply and loans to investors impact housing prices

Restrictions on investor lending reduce the share of properties purchased by investors as well as the relative price of properties of interest to investors

The Reserve Bank of Australia has been in the unenviable position of adjusting the levers of supply and demand for housing. With 12 interest rate rises (equivalent to 400 basis points) since May 2022, the RBA has been applying pressure to the inflation brakes of Australia’s economy, in a delicate balance of cooling down Australia’s overheated housing market, while trying to avoid setting in motion the effects that could potentially spiral into recession.

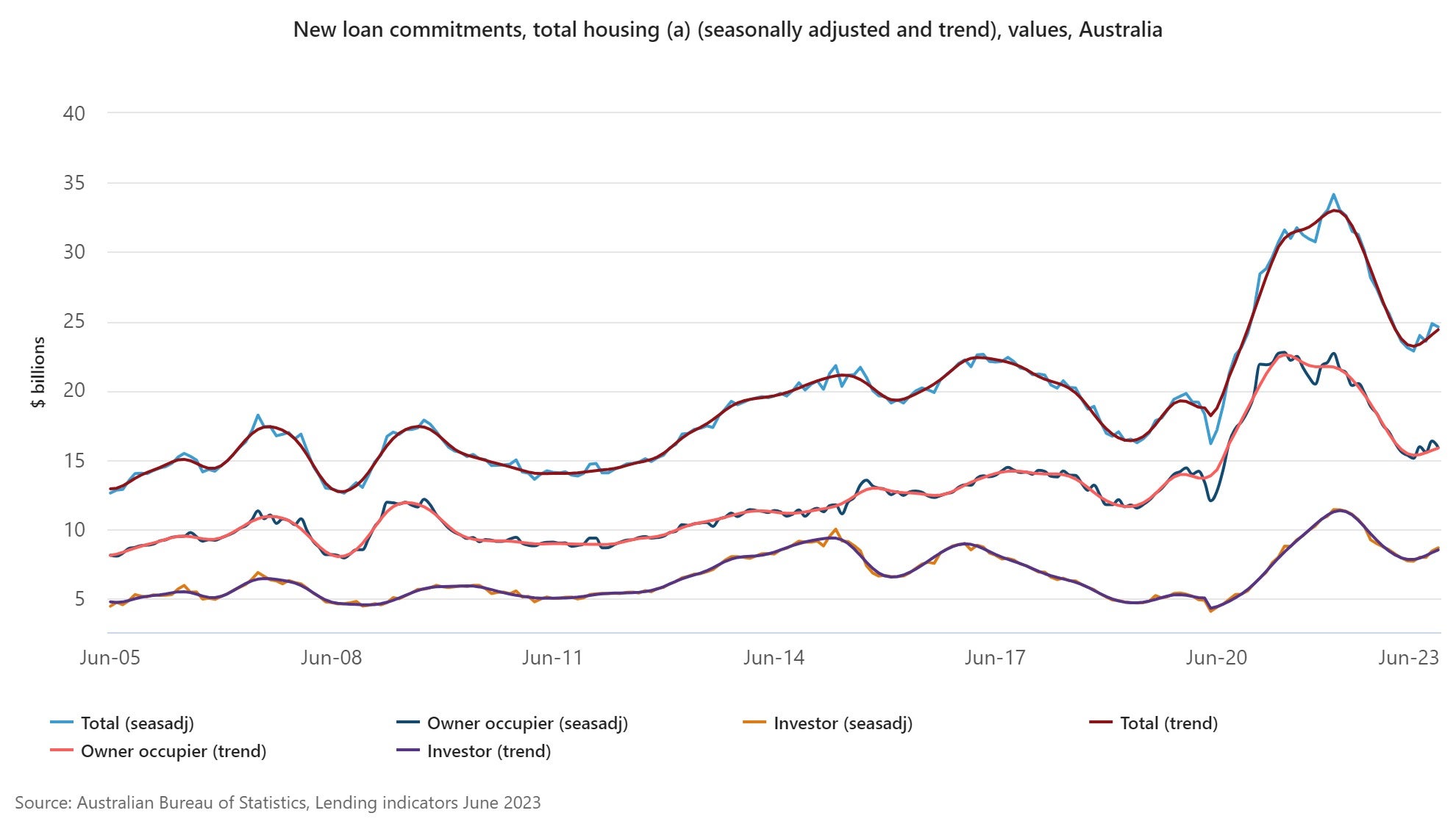

The interest rate rises have had an impact, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, which recently revealed had home lending has fallen considerably in the past year as of June 2023. More specifically, the value of new loan commitments for total housing fell 1 per cent to $24.6 billion, which is 18.2 per cent lower compared to a year ago, while the value of new loan commitments for investor housing rose 2.6 per cent to $8.7 billion – but this is still 15 per cent lower compared to a year ago.

These trends are in line with recent research conducted by Dr Nalini Prasad, a Senior Lecturer in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School. “Policymakers, economists and commentators often become concerned when there are large swings in investor activity. There is a belief that increased investor activity can point to a ‘frothy’ housing market, but we know very little about what influences these swings,” said Dr Prasad.

Downturns in investor activity in the housing market can also cause recessions, according to Dr Prasad, who said it is now widely accepted that housing investors played an important role in amplifying the housing market boom and bust in the United States in the early 2000s, which contributed to the Great Recession. “Regions that had a greater proportion of investor purchases experienced stronger price growth during the boom and larger falls in prices and incomes during the bust, which delayed the recovery from the recession,” she said.

Given downturns in investor activity can produce recessions, she suggested policymakers may wish to impose policies that moderate investor activity during the upswing in the housing cycle. “But we don’t know which policies are going to be effective if we don’t know what drives investor activity,” she noted.

Key research findings

With this in mind, Dr Prasad and co-author, Dr Christian Gillitzer from The University of Sydney, set out to understand what drives investor activity in the housing market. Their resulting research paper, The Effect of Investor Credit Supply on Housing Prices, uncovered a number of key findings – one of which is that restrictions in the supply of bank lending to housing investors reduce investor purchases in the housing market and housing prices.

Dr Prasad pointed to policies implemented by APRA in 2014 and 2017, which were aimed at reducing the supply of loans to investors, were successful in reducing investor purchases and likely reduced housing prices. “I find that a one percentage point fall in the value of new lending to investors leads to a 0.25 percentage point fall in the price of housing more likely to be owned by investors,” she said.

This result is interesting because Dr Prasad observed a substantial fraction of investors (at least 20 per cent) purchase housing without a mortgage. Furthermore, housing investors also tend to have higher incomes and wealth than the rest of the population. “Despite a significant fraction of investors not being sensitive to changes in bank lending and being more wealthy, my research shows that restricting the amount loaned to investors reduces investor activity,” she said.

Read more: What happens to the economy if people can't pay their home loans?

Implications for property investors

Investors are particularly sensitive to restrictions on the amount of interest-only loans that a bank can make. Following a policy introduced by APRA in 2017 that restricted the share of interest-only loans to be less than 30 percent of an individual bank's new lending, Dr Prasad said there were large falls in lending to investors. “I find that a large fraction of prospective investor borrowers were unable to substitute from interest-only to principal and interest loan. This is because required repayments are 30 to 40 per cent higher on principal and interest loan than on an equivalent interest-only loan,” said Dr Prasad.

Getting access to banking finance (especially interest-only loans) is important for housing investors to purchase a property, she explained. “A significant fraction of investors would not be able to purchase properties without a bank loan,” said Dr Prasad, who added that lower investor activity in the housing market is associated with lower house price growth.

Implications for private and central banks

Dr Prasad’s research also has important implications for central banks. Over the past two decades, she said central banks both in Australia and overseas have been concerned that increased investor activity in the housing market could lead to housing price bubbles. To use the words of Glenn Stevens (the former governor of the RBA), there were concerns that investors were being “overexcited”, leading to increased speculation in the housing market that was not supported by economic fundamentals.

“My research shows that policies that restrict the supply of banking loans to housing investors (like what APRA did in 2014 and 2017) can reduce investor activity in the housing market and lower house price growth. These policies can successfully reduce speculative activity by investors,” said Dr Prasad.

An alternative policy would be for the central bank to increase interest rates. While this policy would likely decrease investor activity, she said it might also reduce activity in other parts of the economy where it may not be desirable for activity to be weakened. “For private banks the findings are clear: investor participation in the housing market is sensitive to changes in the supply of bank loans,” said Dr Prasad, who noted that investors in particular are sensitive to changes in the supply of interest-only loans, and may not be able to substitute toward principal and interest loans.

Read more: The great construction company collapse: when your builder goes bust

Implications for consumers and would-be homeowners

For homeowners, Dr Prasad said increased investor activity in the housing market likely signals that house prices are going to increase. While this is good for homeowners, as it will drive up the price of what is likely their biggest asset (the family home), she said this is obviously bad for first-homebuyers – who will now find it more difficult to purchase a house as prices have gone up. “But at the same time, if investor activity is growing too quickly as a homeowner, you should be worried that this is unsustainable and that investor activity will fall in the future and drive down prices. If you are a first homebuyer, this is when you’d like to purchase a property,” said Dr Prasad.

Additionally, consumers’ employment and income are likely to be tied to investor activity, and it has been shown that increases in investor activity are associated with increases in income and employment. “This is because increases in investor activity lead to a boom in the construction of new dwellings, which boosts local area economic activity. Conversely, falls in investor activity are associated with falls in income and employment as construction activity slows down,” said Dr Prasad.

Property markets, demand and crashes

At present, lending to property investors has been relatively stable at about 35 per cent of banks total residential lending, and Dr Prasad said this is well below its previous peak of 45 per cent. “This suggests that currently investor lending isn’t at a level that would be concerning to either the RBA or APRA from a macroeconomic stability perspective,” she said.

In addition, rental inflation is high and increasing, as rental vacancy rates have declined. Dr Prasad suggests one solution to this problem might be to encourage more investors into the market to increase the supply of rental dwellings to reduce rents.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

Based on the current data, Dr Prasad also said it seems unlikely that the behaviour of investors is likely to cause a crash in the housing market in the near term. “A key risk to the housing market comes from the roughly 40 per cent of borrowers who took out fixed rate loans during the COVID-19 period,” she said.

These individuals took out loans with interest rates between 2 to 2.5 per cent, which were fixed for around 3 years. A lot of these fixed rate mortgages are now expiring, and these individuals are having to refinance onto home loans with interest rates between 5 to 6 per cent. “This is equivalent to a $650 increase in monthly repayments for the median borrower. If these borrowers find it difficult to service their new high interest home loans then this could lead to an increase in mortgage arrears and mortgagee sales,” Dr Prasad concluded.