Inside this insider trading loophole: What shareholders need to know

Shareholders who seek out public trading information may be able to spot illegal insider trading sooner and better safeguard their investments from potential fallout from such behaviour

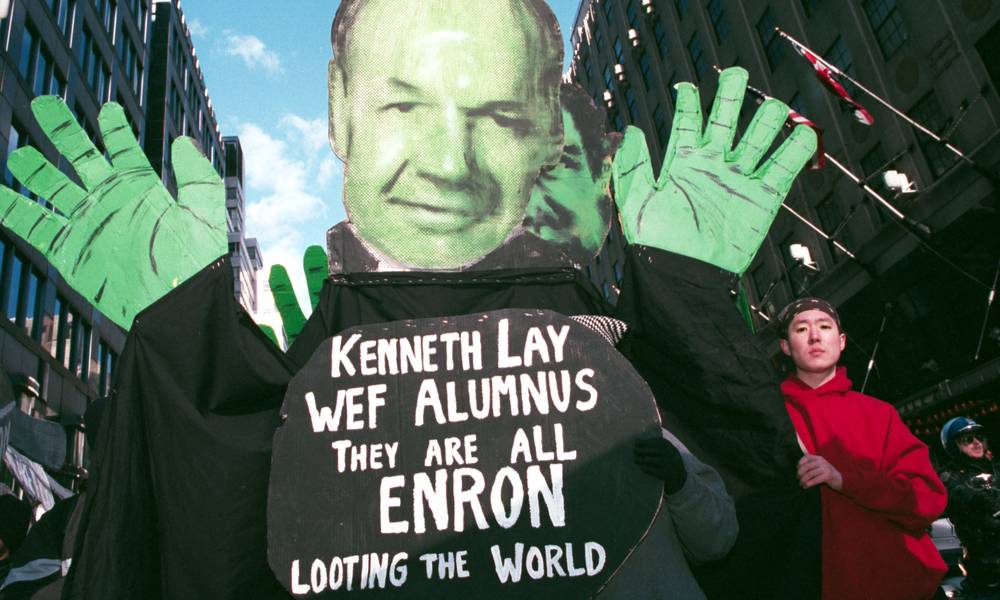

In the most significant corporate financial scandal in US history, Jeffrey Skilling, former CEO of Texas-based energy giant Enron, was convicted on 19 insider trading, conspiracy and fraud charges for misleading employees, regulators and the market.

While Mr Skilling maintains his innocence, both he and his mentor, the company's founder Kenneth Lay, committed massive fraud against Enron's shareholders. In the four years leading up to Enron's bankruptcy in December 2001, shareholders lost a total US$74 billion ($A101 billion).

Lessons from Enron

The story of Enron is one that reached dramatic heights, only to face a dizzying fall. At its peak, the price of Enron's shares went was US$90.75 ($A124.05), compared to US$0.26 ($A0.35) at bankruptcy. The company's colossal collapse shook Wall Street to its core, affected thousands of Enron employees, and is still talked about at length almost 20 years later.

Many have since wondered how such a big business – one of the largest companies in the US at the time – could have collapsed so spectacularly and almost overnight. Worse, how did Enron's executives manage to fool regulators with fake holdings and off-the-books accounting for as long as they did?

The critical thing to remember is that these corporate crises don't just happen overnight: Enron's leadership was using extraordinary means to hide its mountains of debt and toxic assets from investors and creditors for a long time before they were caught.

Following Enron, in 2002, the US Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act to help protect investors from fraudulent financial reporting. Today, independent oversight of the financial statement audit and the financial reporting process is seen as the cornerstone of the modern financial reporting system.

Insider trading linked to lower-quality financial statements

Every year boards must hire an audit committee to verify financial statements, and since SOX this process is overseen by the independent audit committee. Audit committee members, unlike CEOs, are not restricted from buying and selling the company's stocks. Some consider it an extra incentive for the audit committee members to do their job well. But what happens to financial accounting quality when the external audit committee becomes involved in insider trading?

Legal insider trading often happens, for example, when a CEO buys back company shares or when employees buy stock in the company where they work. On the other hand, illegal insider trading is the practice of trading on the stock exchange to one's advantage through having access to confidential information.

But it is often difficult to know where legal insider trading ends, and illegal trading begins. Generally, people will agree that it is wrong to buy shares in the company you run when you know something about it that the market does not, and it is incredibly unfair to buy shares when you are telling the market that things are much worse or better for the company than you know them to be.

UNSW Business School's Dr Sander De Groote, Lecturer in the School of Accounting, says his research finds audit committees that are more actively trading their company's shares seem to be producing financial statements that are of lower quality.

For example, they lack depth and breadth of information, include "aggressive revenue recognition", or are more likely to be misstated, and that "this is an indicator associated with people in the firm trying to get a better result for themselves," says Dr De Groote.

In researching his paper, The Association Between Audit Committee Opportunistic Insider Trading and Financial Reporting Quality (currently in the peer-review process) Dr De Groote examines the insider trading behaviour of a sample of audit committee members in the US.

While Dr De Groote says he does not yet have any causal evidence, he concludes that audit committees with more insider trading also seem to have lower financial statement quality. This means the information will be of lower quality if released to the investing public.

"The primary indicator that I'm using is misstatement risk. Differently put, I relate audit committee insider trading to the likelihood that the financial statements the firm releases every year do not meet accounting standards and need to be changed afterward.”

"Suppose it is discovered that something was not up to accounting standards... that means either someone made a huge mistake in what they put into numbers or, people have been intentionally trying to push the limits to try and get a better result," explains Dr De Groote.

How can shareholders and investors protect themselves?

It is difficult to quantify just how often 'illegal' insider trading occurs. But according to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), there was a surge in suspicious trading before unexpected news from listed companies from 2016 to 2019. An ASIC review of Australian market cleanliness found 5.1 per cent of the volume of traded shares before a material market announcement during these years were "suspicious".

More recently, ASIC advised "heightened share sale fraud vigilance throughout COVID-19 pandemic", reminding Australian financial services (AFS) licensees to be more alert to the possibility of share sale fraud and account hacking throughout the pandemic.

Directors of listed entities must be sure to disclose relevant interests in securities of the listed entity or a related body corporate, including changes to those interests, for example, those resulting from trade. They must also notify the market of any contracts to which they are a party or entitled to a benefit, and that confers a right to call for, or deliver, securities of the listed entity or a related body corporate. The listed entity must make this notification within five business days. If it does so, this notification will also generally satisfy any corresponding obligation to notify the market of this information.

While the disclosure of directors' interests, and trading in those interests, is a fundamental part of ensuring the integrity of financial markets and informed decision-making by investors, it is also up to shareholders to seek out public trading information and to be aware of the risks when potentially investing in a company.

Specifically, shareholders need to be aware of the trading behaviour of the company's audit committee members when evaluating financial numbers that are coming out, Dr De Groote says.

"In the US, that trading behaviour is publicly reported after it took place and it's mandatory. Every audit committee member has to disclose their transactions within two business days of them taking place, right. So that information is generally out there that's available outside investors," he continues.

"It's an extra step that you have to take... but if you see that there's a lot of trading going on in the audit committee that means you need to be more cautious with interpreting the financial numbers," he concludes.

For more information, please contact UNSW Business School's Dr Sander De Groote, Lecturer in the School of Accounting.