Christine Holgate’s ‘principal’ error was applying corporate logic to Australia Post

Private-sector incentives don’t lead to the best outcomes when an organisation such as Australia Post needs to balance a hard-to-measure social mission with a relatively easy-to-measure corporate mission, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

Perhaps the most important lesson from the Christine Holgate controversy is that the confluence of sexism and politics leads to double standards for female executives.

But Holgate’s demise – pushed from her position as Australia Post’s chief executive last November for gifting four senior executives Cartier watches (worth a total of almost A$20,000) in 2018 – is also a good example of how public-sector norms and private-sector competition don’t mix well.

In particular, Australia Post’s status as a so-called “government business enterprise” means it has to serve two masters: its social purpose and its commercial purpose.

Australia Post’s website highlights these two rather conflicting purposes. The very first thing it says is: "Over our long history, our social purpose and commitment to the community has remained the same; to create connections and opportunities that matter to every Australian."

But further down the landing page it asks us if we know that: "Our self-funded government business enterprise is owned by all Australians and receives $0 tax funding. In the past decade, we’ve paid over $1.5 billion in dividends to the Australian Government."

These may not be irreconcilable objectives, but they require very different incentives and compensation schemes for executives in such enterprises than are the norm in the private sector. This all stems from the “effort-substitution problem” – one of the core principles of the branch of economics known as contract theory, for which Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmstrom were awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

The principal-agent problem

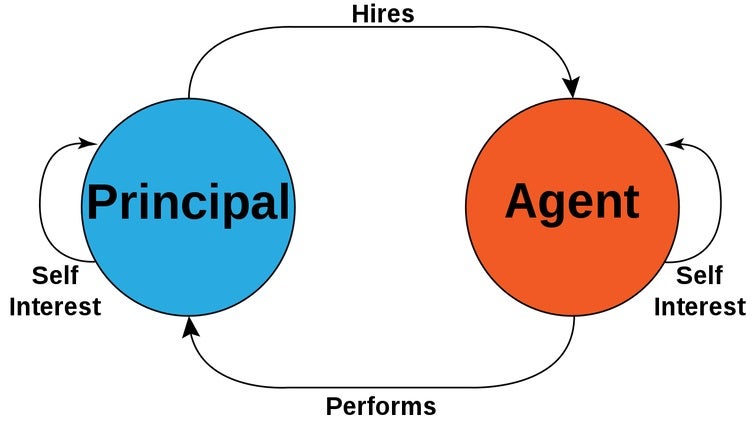

Holmstrom’s contribution for which he shared the Nobel was to advance our understanding of the “principal-agent problem”. This involves understanding how a principal (such as company’s shareholders or board of directors) should optimally design an incentive contract for an agent (such as a chief executive).

The important wrinkle is that the principal cannot observe the effort or actions of the agent perfectly. The principal can only observe a noisy signal of the agent’s actions – such as revenues, profits or the stock price (if the company is publicly traded).

Holmstrom made seminal contributions to this question in the 1970s and 1980s that helped us understand what variables agents should be rewarded on, and why sometimes contracts take the simple form of a base rate of pay plus a performance bonus.

Multitasking and effort substitution

But it is Holmstrom’s 1991 paper – with Paul Milgrom, who won the 2020 Nobel prize for his contribution to auction theory – on the “multitask principal-agent problem” that is most relevant here.

Read more: How market design is transforming the role of economists into engineers

Imagine you are a principal designing an incentive contract for an agent who performs two main tasks. One of those tasks is quite easy to measure. The other is very hard. What should the optimal incentive scheme look like? How “high-powered” should incentives be?

Take the example of school teachers. Let’s simplify things and suppose teachers impart core skills such as reading, writing and mathematics, but also other skills or values such as “higher-order thinking” and “a love of learning”. The former might be imperfectly but reasonably well measured by assessments and standardised tests. Measuring whether primary school children have developed “higher-order thinkings” skills, however, is pretty hard.

Since there are only a certain number of hours in a school day, teachers can’t do everything. Give them high-powered incentives tied to the core skills and they will, at least to some extent, shift their focus to preparing kids for standardised tests. This will reduce the emphasis on higher-order thinking and imparting a love of learning.

This is the “effort substitution problem”. How much a teacher shifts emphasis will depend on their own values and motivations. Some will shift a little. Others, as has been witnessed in the United States, will focus almost exclusively on teaching to the test. Some may even resort to cheating on behalf of students.

Incentives in government enterprises

So it is for executives within government business enterprises. Not the cheating part, but if they have high-powered incentives based on standard private-sector “metrics”, they will do what people do: respond to the incentives. That is what led, in the case of Australia Post, to four executives successfully negotiating a very valuable contract, and to Holgate rewarding them with expensive Cartier watches.

In the private sector none of this would have raised eyebrows. But it didn’t seem to gel too well with Australia Post’s “social purpose”. Or at least, it opened the door for those who saw advantage in attacking Holgate while hiding behind a semi-credible excuse.

The lesson is private-sector incentives don’t lead to the best outcomes when an organisation is trying to balance a hard-to-measure social mission with a relatively easy-to-measure corporate mission.

The path forward for Australia Post

The bottom line is that it’s hard for Australia Post to have two bottom lines. Australia Post can have dual missions, but the “low-powered” incentives required to avoid the effort-substitution problem and deliver on its public purpose means it won’t be as successful at its corporate purpose.

One solution to this quandary is privatisation, but that would damage Australia Post’s social mission. Not once in the history of the world has the privatisation of such services (relying on mandated service standards) ever worked well. The other solution is to tolerate low-powered incentives and live with the fact that dual missions requires balance, and imperfect performance on both.

There’s really no getting around that.

As is often the case, Bob Dylan said it best: “They may call you doctor, they may call you chief, but you’re going to have to serve somebody […] Well, it may be the devil or it may be the Lord, but you’re going to have to serve somebody.”

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub @UNSWBusiness, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative, and President-elect of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. His research expertise includes contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.