How do you fight a recession without precedent?

The current recession is an unusually deep one, and digging out of it will require first containing and defeating the virus followed by significant spending in addition tax cuts, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

It became official last Wednesday. The Australian economy is in recession for the first time in nearly three decades.

And the drop in economic activity is unprecedented. GDP fell 7 per cent in the June quarter. The previous biggest post-War fall in Australia was 2 per cent in June 1974. But Treasurer Josh Frydenberg noted that in March he was told the June quarter contraction might be 20 per cent. In Britain it was.

Bookkeeping aside, the question that matters is how to fight this recession. Answering it requires an understanding that it is a different type of recession to those we’ve seen before.

As I pointed out earlier this year the recessions some of us grew up with in the early 1980s and 1990s were “business cycle” recessions. They happened because the economy overtook its inbuilt speed limit and pushed up inflation. To curb it, central banks pushed up interest rates, pushed them up too far and choked off investment and spending, sending economic activity backwards.

A recession like no other

In 2020 we face a different sort of shock. COVID-19 has hammered economic activity, even more so in countries such as the United States where it has run out of control.

Many of the opportunities we used to have to spend money (such as airlines, theatre tickets and cafe meals) simply haven’t been there. They’ll come back when things return to closer to normal, perhaps though the wide deployment of a vaccine. But we might not spend as we used to.

Some people, out of work or on shorter hours won’t have the capacity to spend. Others will want to rebuild their savings. And others who have been saving big might decide to keep doing it.

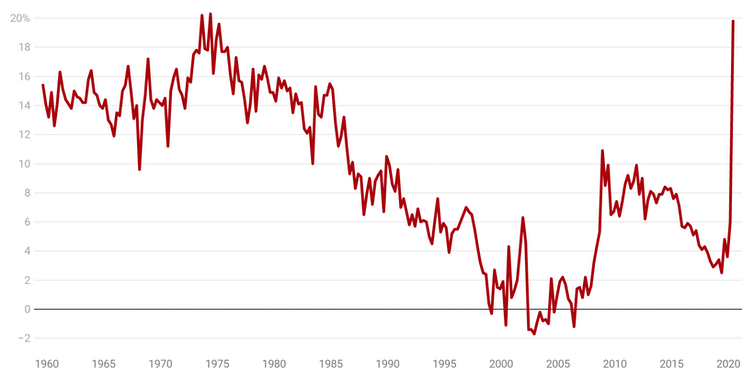

Australia’s household saving ratio surged to 19.7 per cent in the June quarter. It’s a peak not reached since 1974 at a time when there was much less of an age pension and superannuation, no Medicare and surging unemployment. In other words, its at a height not reached since people really needed to save.

The Bureau of Statistics says that if household income from all sources including early access to super was counted, the ratio is even higher. Its estimate of what it calls the “household experience savings ratio” is 24.8 per cent. That means households saved an extraordinary one in every four dollars that came through their doors in the June quarter, up from mere percentage points a few quarters earlier.

Much of it would have been what economists call precautionary saving, understandable given how much of the future is uncertain.

There’s such a thing as too much saving

But what if this extraordinarily high saving rate lasts beyond the point it is understandable, as it did in Japan. As with Japan in the 1990s when saving soared, real interest rates are negative. We are so keen to save we don’t need a financial return.

There were signs of it worldwide, well before the pandemic. President’s Clinton’s Treasury Secretary Larry Summers referred to it as secular stagnation, a term first coined in the 1930s.

Saving more than we are prepared to invest shrinks economic activity. It creates unemployment which itself creates uncertainly, prodding people to save still more than they invest. It’s one of the reasons worldwide economic growth is low, interest rates are low, and inflation is low.

During the pandemic the government is spending more than A$100 billion on measures such as JobKeeper and JobSeeker.

If we won’t spend, out government will have to

Post pandemic it might have to keep spending big on physical and social infrastructure – things such as major projects and better aged care and health care. If we won’t spend big again, it’ll have to. It’ll need to get the economy’s long term growth rate back up to 2 per cent, or even the near 3 per cent the Treasury thinks it is capable of.

It’ll require a lot.

Australia used to have one of the lowest company tax rates in the developed world, now we have one of the highest. We tax labour income too much and consumption too little. And we have a hopelessly out of date and absurdly complex industrial relations system.

Each of those things are a handbrake on economic growth. This is an unusual recession and an unusually deep one. Digging our way out will require us to at first contain and defeat the virus, and then spend like Keynes and cut taxes like Friedman.

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School. This article first appeared on The Conversation.