7 reasons why the government should not bail out Virgin Australia

There are a number of important reasons why the government should not bailout Virgin Australia, according to UNSW Business School Banking & Finance Associate Professor Mark Humphery-Jenner

Virgin Australia has entered voluntary administration. However, both before and after Virgin Australia and its major shareholders had asked for a government bailout. The Federal Government repeatedly rebuffed these requests. Queensland offered $200 million if Virgin Australia kept its headquarters in Queensland. Unsurprisingly, no other state government would match Queensland’s offer.

This begs the question: should Virgin Australia be bailed out? To answer this, we need a rigorous set of criteria by which to judge whether a bailout should occur. That is, taxpayers can only fork out so much money and the government must decide how to ration it. Virgin Australia does not satisfy the criteria for a bailout.

The exogenous shock of COVID-19

The threshold criterion must be that there is an exogenous shock to the company’s finances. This must be due to something that is beyond its control. This was the case with many financial institutions during the Great Recession. Here, COVID-19 was beyond Virgin Australia’s control. In theory, companies could maintain cash stockpiles for a once-in-a-century pandemic. But, myriad companies had not.

A well-run company?

The second criteria is that the company must have been well run. The government should not be in the business of propping up failing enterprises. If a company is bleeding money into oblivion, taxpayers should not keep it on life support. It is not the government’s role to play turnaround specialist and pick companies to attempt to reform and/or to subsidise unproductive operations.

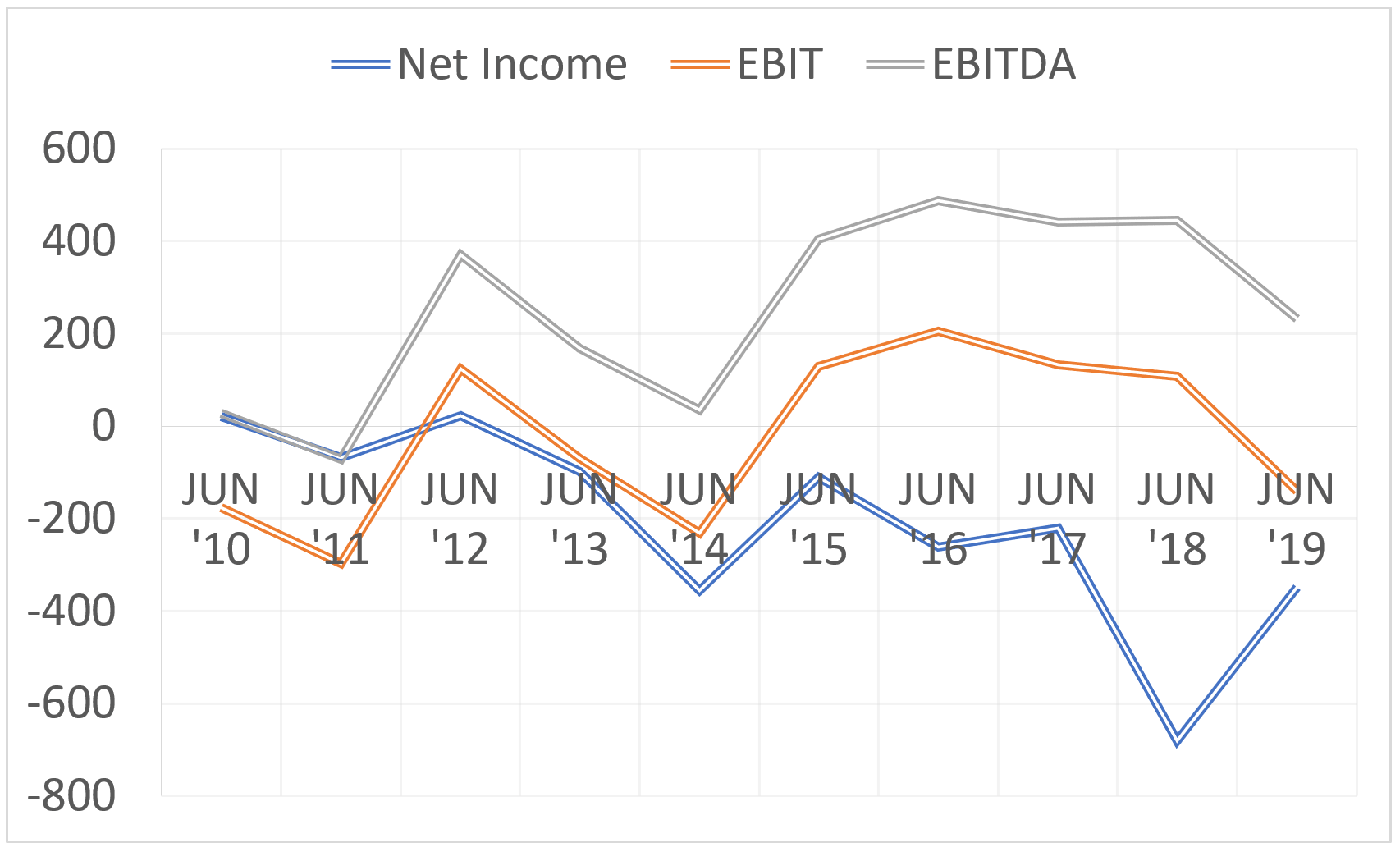

Virgin Australia dismally fails this criterion. Virgin Australia has not made a profit since 2012. Net income has been negative for eight years. Income before tax has been underwhelming. Virgin Australia is not profitable and has not been for a long time. By contrast, Qantas has been profitable for at least five years.

The systemic importance of Virgin Australia

Crises harm many companies. Unfortunately, many companies will fall victim to COVID-19. The government has done an admirable job supporting companies with the limited funds any government can muster. But funds are limited and the government cannot subsidise all companies. Thus, when choosing which companies to save, the government would devote more attention to systemically important companies.

Virgin Australia does employ many people in myriad different areas. Hopefully, many of these jobs will survive Virgin Australia’s restructure. However, myriad restaurants, hotels, universities, and other industries employ thousands of people. And, the government has not bailed out individual restaurants or provided cash to universities. So merely employing people cannot be the sole criterion on which to base a bailout.

Proponents of a bailout make at least two arguments: first, Australia needs a second airline. Second, Virgin Australia is a major employer and Virgin Australia collapsing will destroy many jobs and harm many suppliers. Both arguments are true to an extent.

Competition has myriad benefits. It helps consumers by ensuring better products and/or lower prices. It helps shareholders by disciplining managers and punishing complacency. Thus, a second airline is desirable. However, it is not essential. The ACCC has powers to punish the misuse of market powers. Regulation is a blunt instrument to deal with near-monopoly power, but it reduces the need for a second airline.

What do taxpayers get out of it?

Taxpayers should get something out of any bailout. Otherwise, it creates a perverse incentive for shareholders to simply shift risk to the government on the assumption they will be bailed out. Here, there is a significant problem.

First, the government would not want to lend money to Virgin Australia. The company has not been profitable for over five years. It has little prospect of repaying debt. The government cannot impose collateral requirements on Virgin Australia because it has few assets that would make good collateral. Its aircraft are mainly on lease.

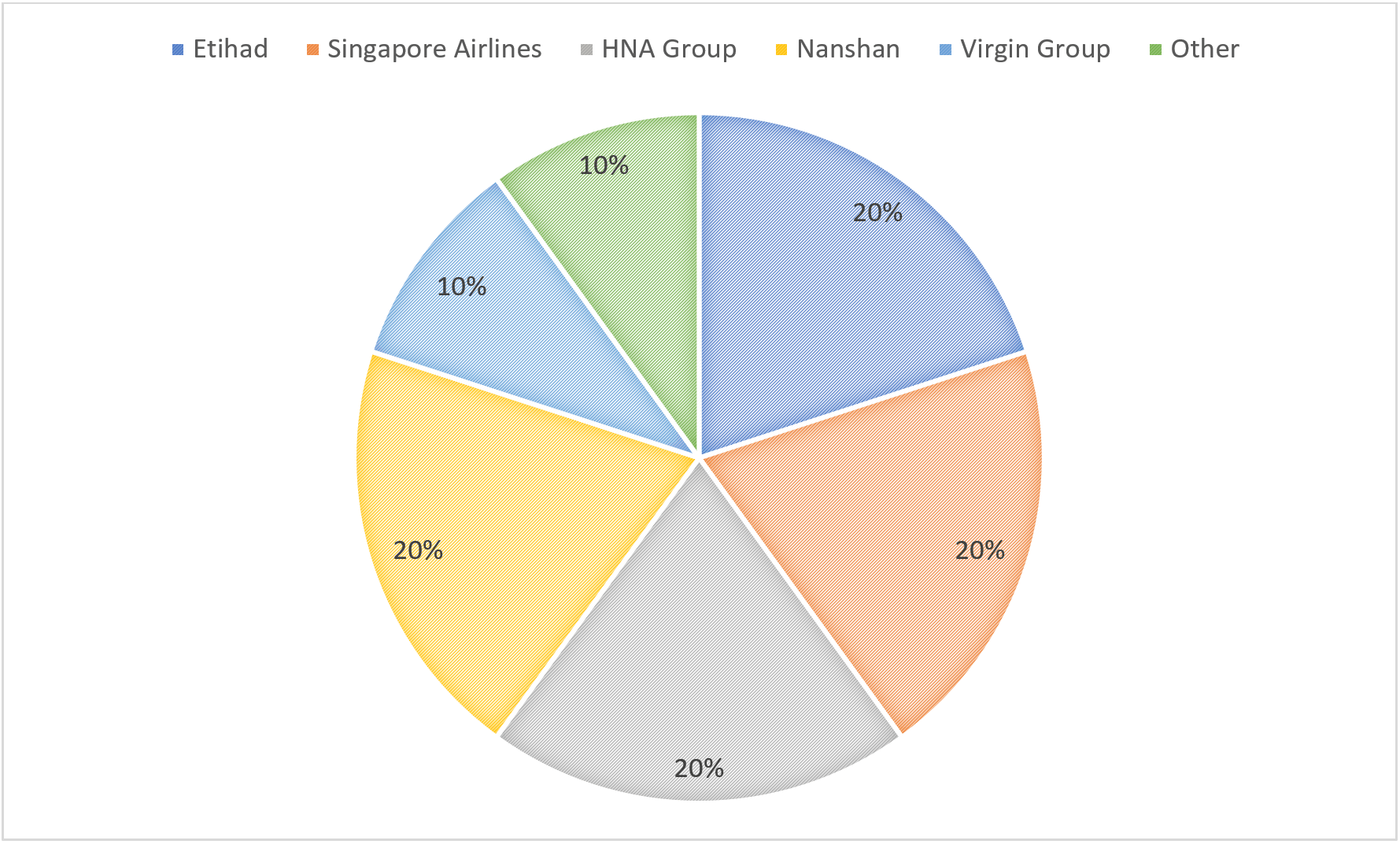

And, while it could sell aircraft and airport slots, these are not liquid. The government cannot force shareholders to provide collateral here because 90 per cent of the shares are owned by overseas corporations and enforcing collateral against them would be a fraught prospect.

Second, equity is problematic. Governments should not nationalise corporations. But a government could hold equity and place it into a sovereign wealth fund, potentially for sale later. Here, however, the shareholding base is highly concentrated. Four shareholders own 20 per cent of the shares each, and one shareholder owns 10 per cent. This could induce principal-principal conflicts, where the government would risk being trampled over. Thus, the government would need 51 per cent of the equity to prevent this. While it is not certain, it appears unlikely that the shareholders would accept this amount of dilution rather than go into administration.

Should shareholders be making the bailout?

A necessary criterion should be that shareholders cannot be expected to make the bailout. In a normal listed company with dispersed shareholdings, this is often the case – and/or companies can show good faith by attempting to raise equity. However, as indicated, Virgin Australia is 90 per cent owned by overseas corporations. The Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has highlighted that it would be disingenuous for the government to effectively bailout those organisations.

For a bailout to be justified, the shareholders should – at the least – demonstrate that they cannot reasonably provide the funding in question. It is quite possible that only some shareholders have capital. In which case, those shareholders could justifiably seek more shares in return for propping up the company.

Is it the best use of money and what precedent does it set?

The government must also consider whether the bailout is the best use of money. A bailout is undesirable it either (a) the government could spend the bailout money better and/or (b) it would set a precedent to open the floodgates to other bailouts.

The government has competing priorities. It must consider whether other companies would more justify a bailout, especially if those companies or organisations have generated significant Virgin Australia value for the country. For example, if the government were to spend $1.4 billion on a company that has been making consecutive losses, it would raise the question of whether it would be better to invest that money a successful industry that has generated significant social returns on capital and is a major exporter – such as the university sector.

Unfairness to Qantas

A relatively more minor issue is whether the bailout is unfair to other companies. Qantas has argued that if Virgin Australia received the requested $1.4 billion bailout, then Qantas should receive $4.2 billion. There is some basis to this. Providing funding to failing companies creates inherent perverse incentives. It penalises Qantas for exercising discipline to remain profitable. It does this implicitly by significantly altering the competitive position of Qantas vis-à-vis Virgin Australia and would render Qantas’ relative discipline irrelevant. The aforementioned concern about why the government would pick Virgin Australia over other industries is also manifest.

What does all this mean?

When we turn our minds to whether Virgin Australia is a good candidate for a bailout, it is not. It has been persistently unprofitable. It has not turned a profit since 2012. It has had negative free cash flow in all but one of the past 10 years. While a second airline is desirable, it is not systemically important. Further, the bailout would effectively be to support five major overseas corporations.

In essence, the only way a bailout could work is if the government treated it as a turnaround project – much like an LBO – in an attempt to reverse Virgin Australia ’s financial affairs. Else, the government would devote scarce resources to overseas corporate shareholders and a company whose financial position could place it in need of more capital in the near future.

Mark Humphery-Jenner is AGSM Scholar and Associate Professor in the School of Banking & Finance at UNSW Business School.