Overcoming inequality: the not-so-hidden-cost of modern economics

We must rethink the political and ideological factors that have led to inequality in order to achieve a new era of economic justice, says French economist Thomas Piketty

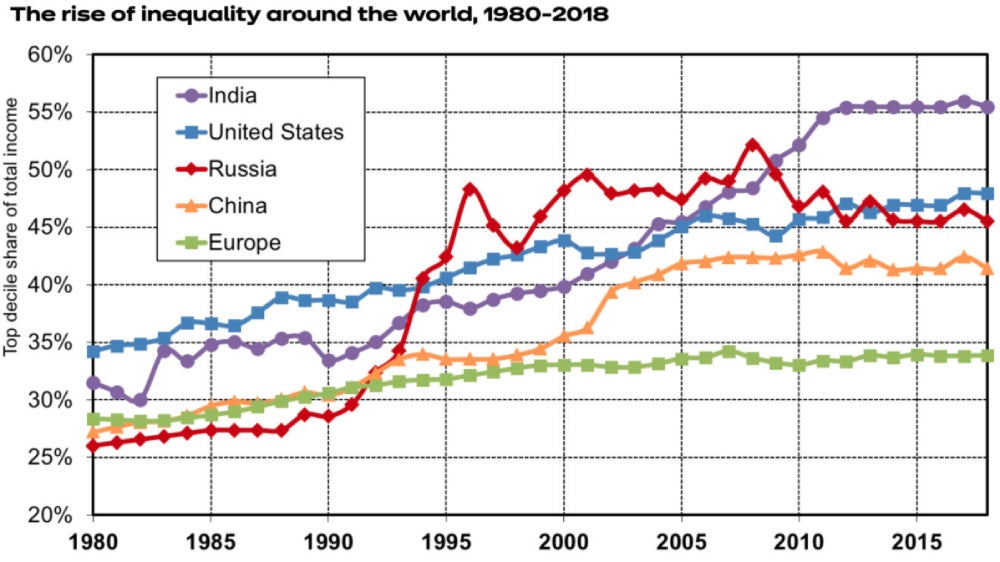

Excessive inequality, in any society, is harmful. Yet income inequality in OECD countries is at its highest level ever: the average income of the wealthiest 10 per cent of the population is about nine times that of the poorest 10 per cent across the OECD – up from seven times 25 years ago.

Even in Australia, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, the differences between the average incomes of low, middle and high-income households are shockingly large. Someone in the highest 20 per cent of the income scale lives in a household with almost six times as much income as someone in the lowest 20 per cent of the income scale.

An economic system that leaves people behind is bad for both the economy and people. So what would need to happen for change to occur? UNSW Business School Professor of Economics Richard Holden recently sat down with Thomas Piketty, Professor of Economics at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, Associate Chair at the Paris School of Economics, and co-director of the World Inequality Lab and the World Inequality Database, for an event hosted by the UNSW Centre for Ideas to explore the basis of inequality in our hyper-capitalist age and how to overcome it.

Political and ideological factors have led to inequality

According to Prof. Piketty, political and ideological factors have bred the inequality we see today. But this doesn't mean that all ideologies are harmful; what it does mean is there are still several ideological problems society has yet to solve.

To better understand this, economists need to embrace their roles as social scientists because the relationship between individuals and societies inherently shapes modern economics. Prof. Piketty articulates this idea in his famed book Capital in the Twenty-First Century. In his latest book, Capital and Ideology, he expands on this discussion and examines inequality as a political phenomenon shaped by ideology and social institutions.

Read more: Paradigm shift: a roadmap for tackling the tough social issues

For Prof. Piketty, inequality is a policy choice and viewing it as a political and ideological issue helps him correct the tendency to view inequality as just another natural fact of life. Unlike the laws of life, policies that lead to inequality (taxing the wealthy, for example) can be changed. Public opinion, scientific findings, technological change, interest groups, NGOs, business lobbying, and political activity play a crucial role in forming public policies.

"I view my work more as the work of a social scientist. It seems the boundaries between economics, history, political science, sociology are much less clear than what economists sometimes pretend, or historians sometimes pretend," said Prof. Piketty.

"We have to rely on methods and modes of inference, which, in a way, are closer to what historians or political scientists are doing."

Things can be different – because they have been

Global history teaches us what has worked (and what hasn’t) when it comes to the equal distribution of wealth. Here, social scientists play a role in helping us remember that things haven't always been this way. In the US during 1945, Prof. Piketty said the top income tax bracket hit an all-time high of 94 per cent for those making more than US$200,000 (A$263,190). The following year in 1946, the top rate was reduced to 91 per cent, and remained pretty much the same until the early 1960s.

Importantly, this was one of the most successful eras in US economic history, said Prof. Piketty. During this time, the US’ middle class, economy and stock market boomed – all with a high marginal income tax rate over 90 per cent. This fact is often overlooked in debates about raising income tax for the wealthy.

"US capitalism did not disappear, as always; we would have noticed it. And if anything, the rates of productivity rose, which is the best measure of innovation that we have," said Prof. Piketty.

Progressive taxation can rebalance economies

"Progressive taxation, of course, is central, both through progressive taxation of income wealth and inherited wealth," said Prof. Piketty. He proposed taxing the wealthy at the highest rate of 80-90 per cent in his latest book.

"The historical experience that we have is that when this was used in the past, this worked pretty well, although that's what I'm trying to show in my book," he said.

Read more: Can we have GST reform without adding to social inequality?

In particular, he suggested learning from the history of US taxes between 1930 and 1980, taking away from history the things that worked, and fine-tuning and improving the aspects where there was clearly room for improvement.

“But by and large I think there's sufficient evidence today that we want to return to that kind of progressive taxation," he said.

While taxation is essential, it is just one tool that rebalances economies. Equal education, worker’s rights in companies and public investment in research are also fundamental, Prof. Piketty added. He explained inequality is the result of ideology and policy choices (and not a natural aspect of life) so there are still ideological issues that need to be resolved.

"The history of the world has been the history of class struggle, according to Karl Marx, and what I suggest as a challenge is to use the history of the world as a history of ideological struggle," explained Prof. Piketty.

Taxing the ultra-rich profiting off human capital

Finally, Prof. Holden noted that “some people argue that inequality is being driven by things like human capital''. But he suggested that maybe it’s not so much the movement of capital, but rather specific companies that are leveraging human capital over the entire world economy.

“So people like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg and the Google guys, might be characterised as people that have had very good ideas that could be leveraged very widely over a large part of the US economy”. But how much of a role does human capital have to play in driving inequality?

“I think the problem is not to regulate the movement of people, the problem is to regulate the movement of capital. I think free capital for all without common taxation is a big problem and was a big mistake,” said Prof. Piketty, who observed the problems in the international financial and tax systems can be reversed to support economic justice for all.

And there is hope. In the US, Senator Elizabeth Warren, Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal, and Congressman Brendan Boyle recently proposed an "ultra-millionaire tax" on fortunes over US$50 million, which if passed, would bring in at least US$3 trillion in revenue over 10 years, without raising taxes for 99.95 per cent of US households.

Thomas Piketty is Professor of Economics at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS), Associate Chair at the Paris School of Economics, and Centennial Professor of Economics in the International Inequalities Institute at the London School of Economics. He is also the co-director of the World Inequality Lab and the World Inequality Database and the author of the critically acclaimed and internationally bestselling book Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub @UNSWBusiness, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative, and President-elect of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. His research expertise includes contract theory, law and economics, and political economy.