How COVID-19 has reshaped manager attitudes about working from home

New research indicates the great working-from-home experiment of 2020 has finally broken the back of managerial resistance, according to UNSW Canberra's Sue Williamson and CQUniversity Australia's Linda Colley

It has been almost 50 years since visionaries first predicted a digital revolution that would enable many of us to work from home. But that revolution has long been thwarted by resistance, crucially, from management that has been concerned about productivity and performance.

Indeed, this was the case in 1974, when Jack Nilles led the first major study to evaluate the benefits of “telecommuting” with a team from the University of Southern California. And it was still the case in 2019, according to researchers from San Jose State University, whose studies showed managerial and executive resistance was the major perceived obstacle to the expansion of flexible working.

Our own research with Australian public service managers in 2018 also found extensive managerial resistance to employees working from home. But more recently, curious about how the enforced experience of working from home might have changed such attitudes, we surveyed 6,000 Australian public servants (including 1,400 managers) in June and July this year and found the seeds for a revolution.

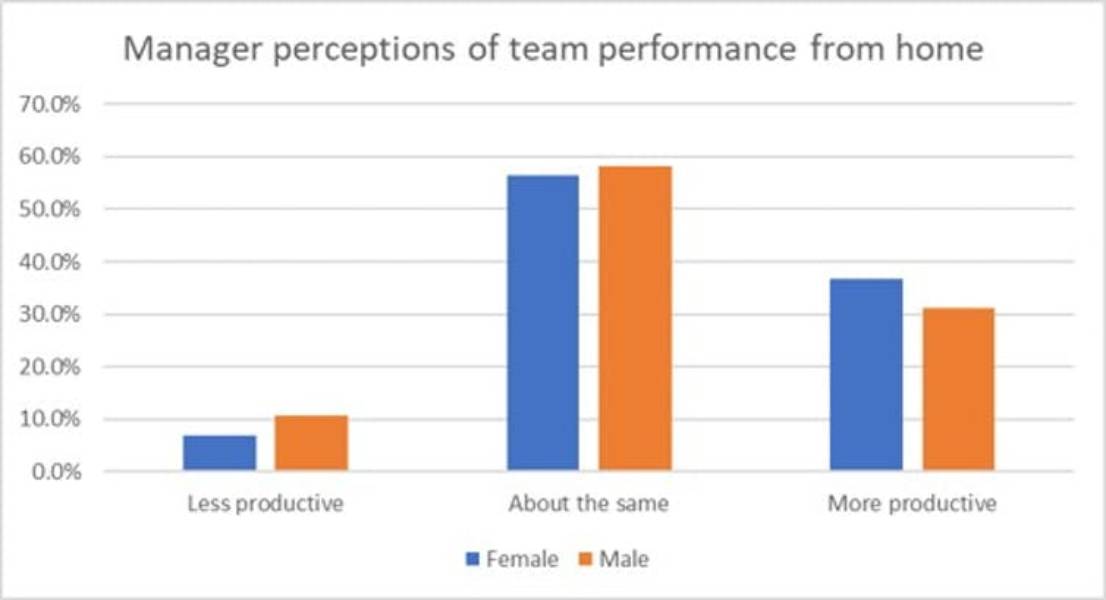

Only 8.4 per cent of managers rated their teams less productive when working from home, while 57 per cent thought productivity the same, and 34.6 per cent said productivity was actually higher. These findings, along with others, suggest working from home, at least for part of the week, may become the norm.

Negative perceptions pre-pandemic

It is difficult to estimate precisely how many people had the option of working from home prior to the pandemic. Australian Bureau of Statistics data published in September 2019 indicated about a third of all employed people regularly worked from home. But it is likely this number also includes workers catching up on work after hours.

In the public sector, about one-third of executives worked away from the office, but less than 15 per cent of non-executive employees did.

Our 2018 research, which involved focus groups with nearly 300 managers across four state public services, found extensive managerial resistance to allowing work from home despite supportive policies permitting it. Managers shared with private sector managers concerns about performance and productivity, and the difficulty of remotely managing workers. They often framed their resistance around concerns about technology or work health and safety.

But on top of this, public service managers were sensitive about agreeing to any working arrangements that might feed community stereotypes about 'public servants having it easy'.

A significant shift in perception post-pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic rendered those objections irrelevant. By the end of May, 57 per cent of Australian public service employees were reportedly working from home.

To find out how perceptions of working from home may have shifted, we worked with the Community and Public Sector Union who distributed our survey. The 6,000 respondents to our survey included about 20 per cent non-union members and 22 per cent managers, across a broad range of occupations and agencies.

As noted, three times as many managers thought team productivity and performance had increased as those who perceived a decrease, with the majority remaining neutral.

Interestingly, female managers were slightly more likely to perceive greater productivity (36.7 per cent compared to 31.1 per cent of male managers), as were managers of teams larger than ten employees.

One manager noted, “people are either productive or not, and it doesn’t matter where they work from”. Others said it had changed their management style for the better, forcing them to realise they did not need to micromanage to get results.

Nearly two-thirds said they intended to be more supportive of working from home in the future (though 2 per cent said they planned to be less supportive). Male managers were the most swayed, with 68 per cent saying they would be more supportive, compared with 63.6 per cent of female managers.

One manager noted: "I had always accepted the department line that working from home is a privilege and not a real workplace. Also, that working from home makes you unavailable and disconnects you from the workplace. Discovered that I couldn’t have been more wrong."

Our results show employees were mostly positive about working from home, with more than four out of five saying it gave them more time with their family, two-thirds saying they got more work done, and three in five saying they now have more autonomy over their work.

The potential downside: longer working hours

Nevertheless, there can be downsides to working from home. As one respondent put it: "I hate my house, it’s cold, and the kids are annoying, the dog stinks.”

The key issues identified by previous research are social isolation, lack of feedback and loss of separation of work from home life.

On the isolation and feedback front, our results were generally positive. Managers indicated communication technology-enabled teams to stay in touch in multiple ways, from instant messaging to video conferencing. While just over 10 per cent stuck to their usual meeting routine, the majority (about 60 per cent) had increased their use of virtual meetings. This included scheduling social activities such as virtual coffee and drinks.

On the question of work-life balance, our results were more mixed.

Three-quarters reported they continued to work their usual work hours. But one in four reported working longer hours. Mostly this was due to increased workload, though almost 15 per cent said they had been working more voluntarily because they were absorbed by their work. Many managers noted this increased motivation and mood.

Given the focus on public service, we cannot presume these results apply across the entire workforce. That said, longer working hours do seem to be a common feature of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on data from more than 3 million in 16 cities, researchers have found the average workday for those under lockdown is about 48 minutes longer.

These findings on longer hours potentially offset some of the positive perceptions of productivity improvements. The emergency conditions in which both managers and workers have been prepared to go the extra mile cannot become the baseline for expectations permanently.

Despite these caveats, and the need to point out that organisations still have much to do to embed flexibility in their cultures, our results add to the evidence that the great working-from-home experiment of 2020 has broken the back of decades of inherited managerial resistance. The revolution is upon us.

Dr Sue Williamson is a Senior Lecturer in Human Resource Management in the School of Business at UNSW Canberra. She is joined by fellow researcher and co-author Linda Colley, Associate Professor of Human Resource Management and Industrial Relations at CQUniversity Australia. This article first appeared on The Conversation.