Why do central banks often get their forecasts wrong?

While central banks certainly have a difficult job, they do make life more challenging for themselves, writes UNSW Business School's Mark Humphery-Jenner

Why do central banks often get it wrong?

Central banks have made some infamously bad predictions. Jerome Powell insisted that inflation would be ‘transitory’ and did so long after analysts suggested it was not. RBA Governor Lowe insisted that the RBA would not raise rates until 2024. ECB President Lagarde asserted that it would be ‘very unlikely’ to raise rates in 2022.

Why then do central banks seem to make so many errors? And are they as bad as they are sometimes made out to be?

Forecasts are difficult

Forecasts are more difficult than some commentators make them out to be. For example, when making forecasts, analysts and central banks must determine what variables might influence the focal outcome. They must distinguish between quality indicators and noise. They must determine the interrelationship between variables.

Central banks must further determine the appropriate way to model outcomes. For example, they might need to choose between statistical regression models, gravity models, or other modeling techniques. These themselves do not have perfect predictive power.

Data also has measurement issues and can update over time. Oft-times forecasts use proxies for underlying economic concepts. For example, there are myriad measures to capture ‘consumer sentiment’, all of which are approximations. Further, data can change over time. This explains why the Atlanta Fed GDPNow forecast changes frequently.

Read more: Should interest rates be capped?

Messaging has challenges

Central bank messaging is difficult. Central banks communicate predictions to the market. However, often these predictions are over-simplified.

Forecasters might model myriad scenarios: equivalents of base, bull, and bear cases. However, they only communicate the expected value of these scenarios. That expected value is simply the probability-weighted average of those scenarios’ outcomes. The expected value need not be exactly equal to any of the outcomes in any state of the world: it is an average. However, the communications make it appear as if that average is a pinpoint forecast.

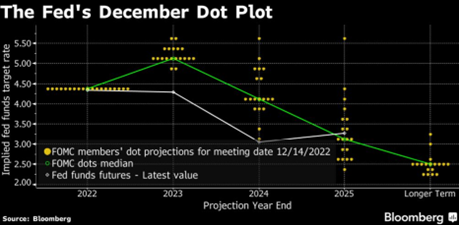

The dot plot is an example. Individual central bankers present their point forecasts for various economic outcomes. However, this buries the nuance behind each central bankers’ prediction.

The recruitment and incentive problem

In many organisations, human capital is one of the greatest resources. However, myriad organisations fail to appreciate how to attract and retain good staff. Some bosses wonder where all the go-getters went. However, much comes down to incentives.

Central banks and government agencies often do not pay nearly enough to attract ambitious talent. If there are bonuses, performance fees, or upside, workers might pull overtime, work weekends, or dedicate themselves more. However, if a company pays under market and offers no upside, people will not ‘go above and beyond’.

The role of incentives has been recognised in the executive compensation literature for decades. It is why founders have equity, banks pay bonuses, and fund managers get performance fees. You do not get investment bank hours, or cutting-edge innovation if you underpay. This should come as no shock to an organisation in the economics and finance field. But, this notion seems to escape government-affiliate organisations.

Central banks thus lose many hard working, innovative, or ambitious employees to places with more upside. Investment banks, super funds, and portfolio managers all offer better pay with more upside. Central banks can retain some of those people. However, they then are left implicitly under-staffed, potentially driving burnout and hurting productivity.

Read more: Why RBA's forward guidance on interest rate policy is a dangerous game

The objective function

We must also consider central bankers’ motivation. Consider the following questions:

- Does the Fed lose more from letting inflation persist or from triggering a recession?

- Do central banks lose more from overstating inflation estimates, or understating them?

- If the bank’s credibility is already gone, do they take a ‘big bath’ and release dire forecasts in the hope that positive surprises in the future will generate goodwill?

All these factors impact banks’ activities and messaging. This can sway the bank’s communications, and make the bank look more inaccurate than is really the case.

Salience bias

We should also acknowledge the role of salience bias. People focus on news that appears more poignant and noticeable. They focus less on unsurprising, underwhelming, or benign news. Thus, people focus relatively less on the times central banks are correct. And, they focus relatively more on the errors. This is especially the case if the media emphasises those errors.

Salience bias cannot explain the full issue, however. The Federal Reserve’s transitory rhetoric was wrong at the time and economists were saying this. The RBA’s claim that it would not raise rates until 2024 was wrong at the time and people warned. Certainly, in both cases, there was a possibility that inflation would be transitory or rates would not rise, but this was not a certainty. And, the central banks erred in making a mere possibility out to be certain.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis, and insights from UNSW Business School

What then does this mean for central banks?

What then should central banks do? Are the wholesale errors they must address? Or, are we overstating the issues?

Central banks certainly have a difficult job. Forecasting is hard. Data is messy. New modeling techniques arise near continuously. Modeling is not as easy as the media makes it out to be. Central banks do, however, make life more difficult for themselves.

Central banks should improve their messaging, if only to better communicate probabilities and scenario analysis to the public. Central banks should better incentivise employees: an organisation that foregoes incentives will not get the most out of its talent, potentially risking ambitious talent leaving for greater upside and remaining talent ‘quiet quitting’.

Mark Humphery-Jenner is an Associate Professor in the School of Banking & Finance at UNSW Business School. He has been published in leading management journals, and his research interests include corporate finance, venture capital and law. For more information, please contact A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner directly.