How our brains blind us to 'black swan' economic events

Neurobiological factors blind people to making sound investment decisions when markets are hit by large macroeconomic shocks, according to UNSW Business School research

Australia will endure the most significant economic hit since the onset of the Great Depression due to the coronavirus pandemic, according to predictions by the International Monetary Fund. Are we about to confront a scenario as bleak as the 1930s?

According to Scientia Fellow Elise Payzan-LeNestour, Associate Professor in the School of Banking and Finance at UNSW Business School, the outbreak of coronavirus was and still is an ‘interesting natural experiment’ illustrating how people, particularly investors, initially misinterpret the nature of major unpredictable events (known as black swan events). They tend to grossly underestimate their importance before eventually readjusting their view – though by which time it may be too late.

“Our brain is deceiving us in a pervasive and systematic fashion,” says A/Prof. Payzan-LeNestour. Her latest co-authored research paper: 'Outlier Blindness': Efficient Coding Generates an Inability to Represent Extreme Values sheds light on the neurobiological foundations of this bias, which is at odds with behavioural patterns previously described in behavioural science. With her collaborator from Columbia University, she called this bias “outlier blindness”.

Such novel insights speak to the way all of us might initially underreact to an unprecedented event and offer essential insights for handling future crises.

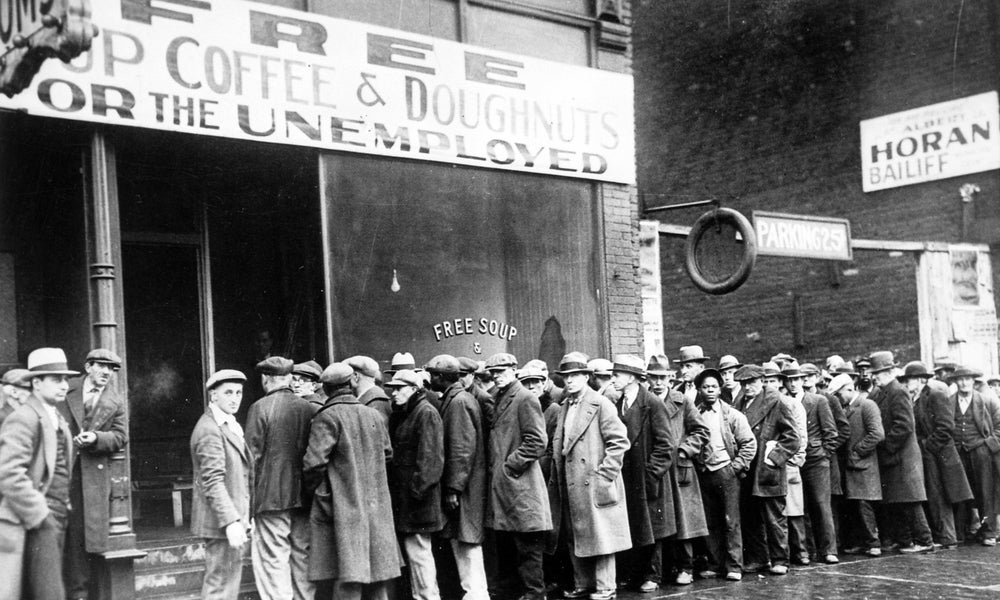

Lessons from the Great Depression

In 1929, global markets enjoyed a stable year, then fell suddenly by 25 per cent in one week during October. Markets then moved sideways for a while. Many back then assumed the downturn would pass without much further damage – but they missed the fact that a permanent shift had occurred in the world.

During the Great Depression, real GDP may have contracted by 10–20 per cent, as Australia suffered years of high unemployment (which reached a peak of 32 per cent in 1932), poverty, low profits, deflation, and lost opportunities for economic growth.

And during this time, the government cut spending drastically. As we now know – thanks to Keynesian economics – fiscal contraction only adds fuel to the fire in times of widespread falls in demand.

So, if history is anything to go by, Australia needs more government stimulus – not less, inasmuch as the current downturn is not the sign of a temporary crisis but of a permanent shift. The findings by A/Prof. Payzan-LeNestour’s research suggests people tend to grossly underestimate the sheer significance of events like the Great Depression while they are living it, and as a result, they do not react as quickly as they should.

Insights for business and finance

The theory proposed by A/Prof. Payzan-LeNestour and colleagues also sheds light on investor risk attitude in the aftermath of COVID-19, which is quite puzzling at first. Recent research provides evidence that on one hand, COVID-19 made investors more risk-averse for a given level of perceived risk (which is quite intuitive; this probably occurred because of increased fear and panic).

On the other hand, COVID-19 decreased investors’ perception of a given level of risk, which is also quite puzzling and one potential explanation for why the S&P 500 has rebounded 32 per cent since late March. Many market observers are calling this ‘a disconnect from the deteriorating fundamentals’, says A/Prof. Payzan-LeNestour. Why is this?

The theory she proposes predicts exactly such a pattern, which she recently described in detail with co-authors from UNSW and UTS. “Following the extreme volatility of March, investors subsequently underestimated risk, leading to inflated valuations through downward biased discount rates, leading to a market rebound until such time as perceptions revert towards objective measures of risk,” she explains.

So, what is causing investors’ temporary underestimation of risk following their exposure to extreme volatility? “The brain becomes adapted to very high levels of volatility reasonably quickly – so completely crazy levels of volatility can become the new normal,” she showed in an experimental study.

"Awareness of our own perceptual biases may help us become less susceptible to them, even though they are very ingrained"

Associate Professor Elise Payzan-LeNestour, School of Banking and Finance at UNSW Business School

Insights for all of us

“Awareness of our own perceptual biases may help us become less susceptible to them, even though they are very ingrained,” says A/Prof. Payzan-LeNestour.

“If you are conscious of them, even if part of your brain is still deceiving you, you may be able to adjust your decision-making,” she explains.

“Ironically, even I (and I’m supposed to know about outlier blindness) was blind to the importance of COVID-19 for months, in the sense that I grossly underestimated its importance and didn’t realise until a few weeks ago that our world will never go back to what it was before,” confesses A/Prof. Payzan-LeNestour. “I guess this reflects the fact that as any scientist, I try to view my own theories with a healthy degree of scepticism.”

She says that, hopefully, the dissemination of her research into the neurobiological foundations of investor decision-making will help people anticipate how they are going to react to the next tragedy and correct their view accordingly.

Do you think COVID-19 is a turning point in history, or as A/Prof. Payzan-LeNestour puts it, are you still “blinded”?

For more information, contact Scientia Fellow Elise Payzan-LeNestour, Associate Professor in the School of Banking and Finance at UNSW Business School.