Bounce-back in private business investments signals possibility of very good news

The latest figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reveal businesses are optimistic about the future and are looking to expand despite ever-present uncertainties, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

Private business investment is one of the key drivers of economic growth.

Business investment in equipment (and even in buildings) drives productivity, which the Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman famously observed: “isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything." As he put it, a country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time “depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker”, which is why one of the forecasts in this month’s budget stood out.

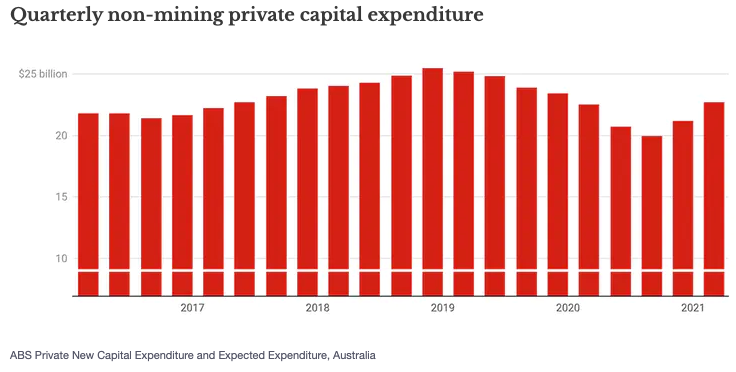

The budget forecast non-mining business investment to grow 1.5 per cent in the coming 2021-22 financial year, after falling last year and then to jump a huge 12.5 per cent during 2022-23. Thursday’s capital expenditure figures released by the ABS are important not only because they tell us what private firms have been spending on plant and equipment and buildings and structures, but also what they are planning to spend in the months and years ahead.

The survey that points to the future

Economists like me are pretty sceptical of surveys. We like to see what people actually do (so-called “revealed preference”) rather than what they say they intend to do (“stated preference”). But the bureau has a decent track record with this survey. In part, that’s because the people surveyed are the chief financial officers of the major firms. They tend to report what they know is in train rather than “spin” grander visions.

And they usually understate what eventually happens. On what has actually happened, their reports suggest that private non-mining business investment bounced back 7.1 per cent in the first three months of this year. In the six months to March (since September) it jumped 13.8 per cent, after falling 11.4 per cent in the previous six months of COVID restrictions leading up to September.

When it comes to what lies ahead, the estimates for 2021-22 are picking up. The March estimate is up 11.3 per cent from the estimate made in December.

It is still well down on the latest estimate for 2020-21, about 13 per cent down. But actual non-mining investment is usually somewhere between 30 per cent and 50 per cent higher than what’s expected (the bureau calculates “realisation ratios”), meaning there’s a good chance it will meet the budget forecast for 2021-22.

Whether it will make it over the much larger bar of the 12.5 per cent increase forecast for 2022-23 is an open question. The point is the figures published on Thursday give us no reason for thinking it couldn’t. The ABS has left open the possibility of very good news.

The bounce-back in investment exceeds market expectations.

Better, and better than expected

JP Morgan reports that the consensus of forecasts was for an overall increase in investment (mining and non-mining) of 2 per cent in the March quarter. We got 6.3 per cent. It matters because it tells us businesses are feeling optimistic about the future — optimistic enough to expand, notwithstanding ever-present uncertainties.

Read more: Wages growth desultory, unemployment stunning

We don’t know when our international borders will reopen. We don’t know how long Melbourne’s newest lockdown will last. We don’t know whether enough Australians will be vaccinated to reach herd immunity.

And the results also matter because more business investment will be needed if we are to drive unemployment down to the government’s new (and welcome) target of somewhere below 5 per cent.

The extra jobs will have to come from enterprises employing more people. They won’t do it unless they think it is worthwhile to invest.

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub @UNSWBusiness, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative, and President-elect of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. His research expertise includes contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.