Betsey Stevenson makes the case for a new model of marriage

Shifting economic incentives are not dooming marriage, but changing who marries (and when), according to labour economist Professor Betsey Stevenson

Steady gender equality gains have altered family and work patterns over the past century, boosting women’s role in the workforce – even as men’s declining participation prompts concern. These changing labour dynamics reflect a new economic model of marriage, said Professor Stevenson, a Professor of Public Policy and Economics at the University of Michigan.

She observed that seismic shifts in technology, legislation and global trade prompted women’s labour gains, while the pandemic laid bare the limitations of current policy for both mothers and fathers, according to the labour economist. Understanding this new paradigm will be essential in another era of substantial technological change, said Prof. Stevenson, who recently presented the Cunningham Lecture, the flagship annual public lecture of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia.

Hosted by UNSW Sydney, the focus for the lecture this year was “Marriage, family and work in an age of rising gender equality”, and Prof. Stevenson said economics can help explain some of the profound changes in labour and family dynamics over the past century.

Shift from specialisation to companionship

Families in the labour force are deeply connected, with decisions creating interdependencies that, in turn, shape the benefits and costs of other choices, according to Prof. Stevenson, who is one of the world's leading labour economists, having been Chief Economist at the US Department of Labour, and recently serving on the Council of Economic Advisers to the President of the United States.

Looking at the progress narrative for women over the past 100 years, Prof. Stevenson noted that the birth control pill gave women more reproductive control while household technological advances reduced what she called the skilled-unskilled bias in the home. This increased women’s workforce participation. At the same time, she said legal and policy changes reinforced these shifts, while the decreasing costs of global trade devalued homemaking skills.

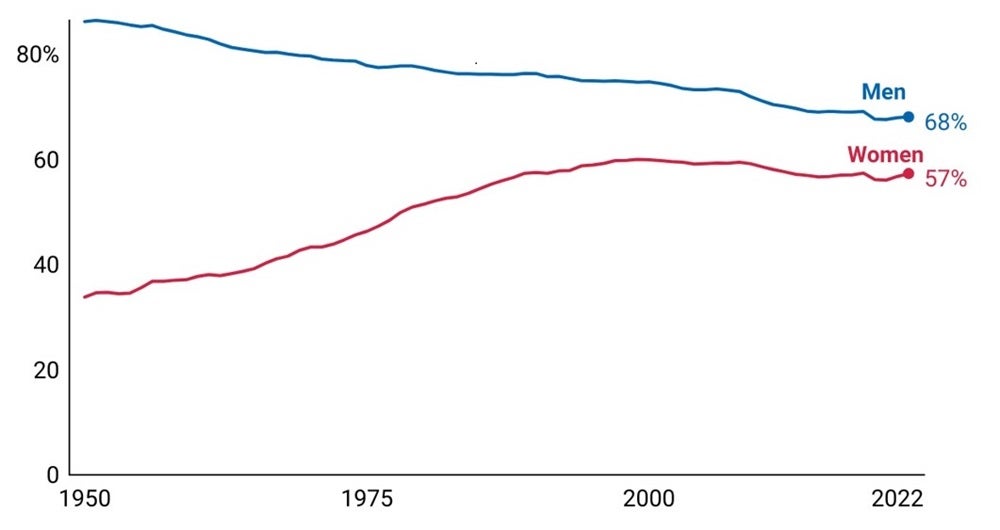

Men's labour force participation has declined and women's participation has risen

The result has been a shift from a marriage model based on production complementarities, with one spouse in the home and the other in the market previously, to one based on consumption complementarities, as economic specialisation gives way to companionship as the primary driver of marriage.

“What we have now is people who want a little bit more certainty about how they want to live their life before they form a relationship with somebody for whom the main benefit is going to be living a life of shared companionship,” she explained. “So, we expect to see an increase in the age of marriage, and we also expect to see couples spending more time together.”

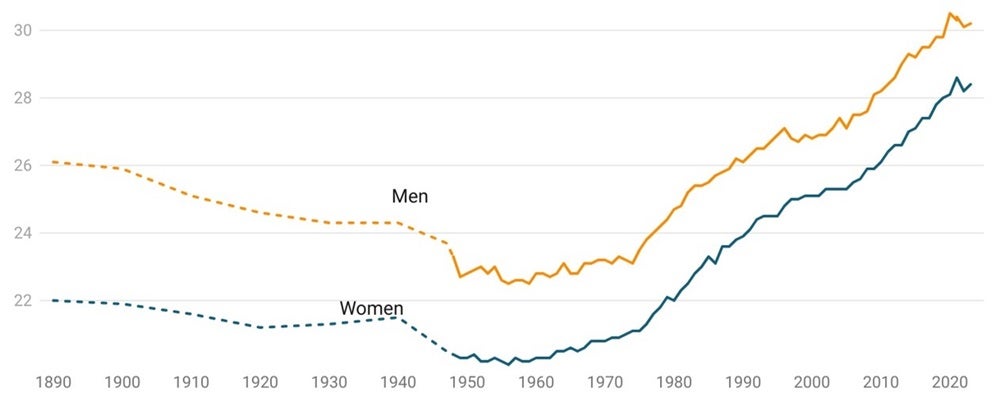

Marriage and childbirth are happening at older ages. Median age at first marriage, by gender

It’s essential to recognise the interconnectedness of these changes, Prof. Stevenson said, as public opinion and public policy interacted over decades with profound implications for marriage, family and work.

And while there is a wealth of research about the forces contributing to women’s rising labour force participation and the narrowing of the participation gap, she said the concurrent decline in men’s participation is less understood, while long-term declines in marriage rates puzzle economists.

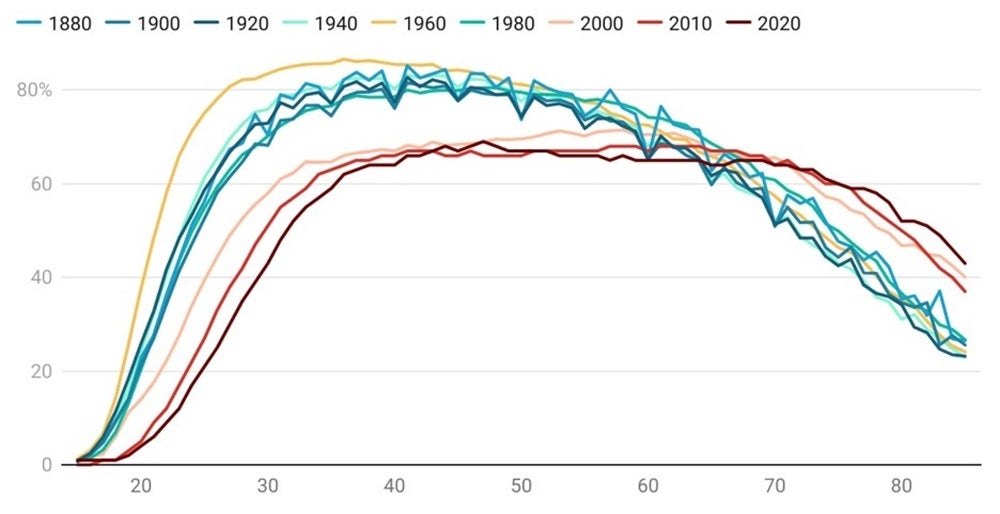

Marriage rates, percent of US population, by age

Who marries, and why?

The question of why people marry is central to economic concerns about family and labour dynamics. According to Prof. Stevenson, the answer has changed dramatically over the decades as the technological, legal and trade shifts have played out.

Contrary to some economists’ fears about the failure of marriage, she explained that the age at which marriage thrives is merely changing as the benefits and returns shift from a production-based to a consumption-based model.

In that context, the puzzle is not why marriage has declined, but why it hasn’t declined even more, “given the absolute decimation of the value of production complementarities as a result of technical, trade and legal changes”, Prof. Stevenson said.

This is important because she said the world is “on the cusp of another revolution” – in the form of artificial intelligence (AI) – that will see many skills replaced by technology. “The question will be, will we be able to respond in the same way that, frankly, women around the globe did when they were booted out of their homes, when their skills no longer have the same value?”

It’s also important to recognise that policy changes often have unintended consequences. Prof. Stevenson pointed to legal changes shifting incentives within the household involving the investments people were willing to make inside marriages, bringing more women into higher education and male-dominated fields.

“Taken together, all these societal changes altered the benefits of marriage so that the benefit of specialisation between market and non-market disappeared,” she explained. “We have an opportunity cost of specialising in non-market work rising because it’s becoming easier for women to get jobs in the labour force where they can bring the full force of their talent to earn equal pay. At the same time, the benefits of staying home are decreasing.”

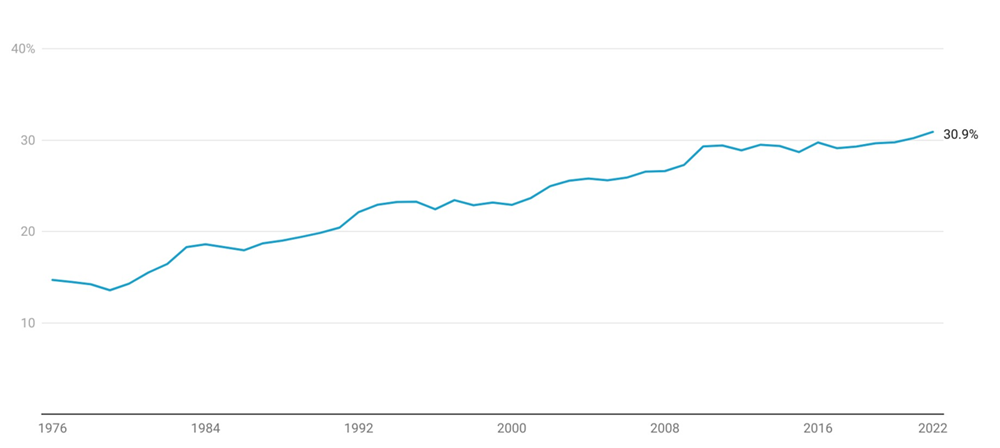

A climbing share of wives make more than their husbands, as a percentage of opposite-sex married households where both spouses work

As such, she said, if one looked at marriages today and expected only production-based ones to thrive, there would be fewer marriages. Instead, the shift to consumption-based marriages is observable, with more marriages of equal partners and the rise of same-sex marriage.

“That increases the benefits of shared public goods within a marriage, increasing consumption complementarities within marriage, increasing marriages of equal partners,” Prof. Stevenson said. “Specialisation becomes more narrow or non-existent. This gives us a new model of marriage, where the benefits come from people with shared interests in life goals.”

A new tech revolution

Recognising the interconnectedness of these changes will be essential to how societies respond to the labour market challenges likely to accompany the next cycle of technological evolution, according to Prof. Stevenson. However, that evolution likely will take 40 to 50 years rather than the ten years some optimists predict.

But the longer diffusion path for AI means there will be time to shape policy for the public good, which will be especially important as the technological replacement of skill aggravates generational challenges, particularly for young people in the labour market.

“The real question will be how many young people wake up to that and what they decide to do about it,” she said, noting that this cohort is already agitated about climate change and squandered resources. “If we layer on that they can’t afford to buy a house, there are no entry-level jobs, there are no resources for you, the question will be what that does to our political system.”

Read more: The productivity divide: how AI will separate the strong from the weak

Prof. Stevenson also hoped the changes in work culture and flexible work as a result of the pandemic would continue and enable more equal partnerships – and that the penalties women face around wanting flexible work would also decrease.

The future of thriving marriage

As gender equality rises and marriage centres more on consumption complementarities, Prof. Stevenson said the profile of who marries changes, as do the timing and reasons for marrying. Again, this has economic implications that belie the feared downfall of marriage.

She explained that marriage will likely become more common among people who can afford more leisure time and public goods. Changing incentives also mean the age of first marriage will likely increase as people become more invested in knowing themselves before marrying for companionship.

“Policymakers often invert and get it wrong; they think marriage will make you financially stable when it’s actually financial stability that makes it easier to be married,” Prof. Stevenson said. “That’s because the benefit of marriage is not from being in the shared struggle together in trying to combine your talents to produce more, but from combining your resources to enjoy more. And if your resources are thin, there’s less of that.”

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

The problem today, as the pandemic emphasised, is that families struggle under workplace norms and policies shaped when marriages were about production complementarities. Meeting the coming challenge will require a holistic view of the new economic model of marriage.

“Today’s marriages thrive when couples have the time and money to enjoy shared interests,” Prof. Stevenson said. “Equality in the workplace and in the home is a joint venture that we are going down together, and policy can impact marriage and work in unexpected ways. So, with more technological change on the horizon, remember that it’s all intertwined.”

Prof. Stevenson will be speaking at the AGSM 2024 Professional Forum: Sustainable Leadership in an Accelerating World, which will be held at the Hyatt Regency Sydney on Tuesday 18 June from 8:30am - 2pm AEST. Prof. Stevenson will open with a keynote on creating a fairer economy for a more sustainable future and how organisations and leaders can ‘think like economists' to influence sustainable, inclusive business practices and decision-making and understand the relationship between economics, leadership and change.