We're doing well despite Delta, but 3 major economic challenges loom

Australia faces problems with its economic road to recovery if three big structural reform areas are not addressed, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development recently published its first Economic Survey of Australia since 2018. It gives Australia good marks for a remarkably good economic response to the COVID pandemic, but warns of the importance of not shirking reforms needed for long-term prosperity.

The Reserve Bank of Australia’s Governor, Philip Lowe, also addressed Australia’s recovery last week, in a speech to the Anika Foundation, which funds research into adolescent depression and suicide. Lowe has made a speech annually since 2017 to help raise funds for the foundation, as his predecessor Glenn Stevens also did.

Lowe was upbeat about Australia’s recovery from the pandemic, and also had important observations about Australia’s economic outlook. He emphasised the central bank would not be lifting interest rates to curtail the latest spike in house prices. The OECD report warns the Australian government relies too much on income taxes for revenue. It also argues forcefully for the significant economic benefits in Australia doing more to reduce carbon emissions.

Taken together, these two assessments point to the outstanding job done in managing the economic recovery. But they also tell us we will have economic problems down the road if three big, structural reform areas – housing affordability, the tax mix, and decarbonisation – are not addressed.

Recovery signposts

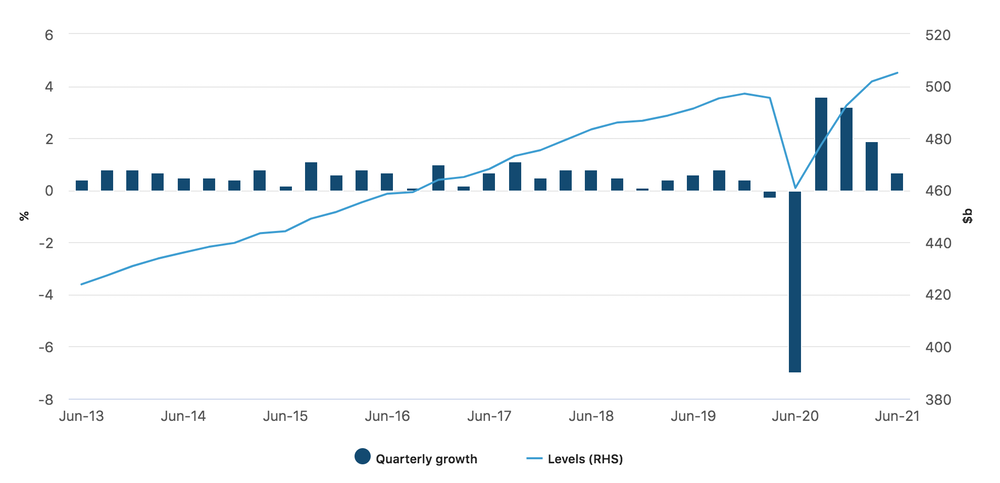

In his speech, Lowe painted a helpful picture of the path of Australia’s recovery before the Delta outbreak – with the unemployment rate hitting a 20-year low and GDP growth recouping all its 2020 losses. At the end of the June quarter, domestic final demand was more than 3 per cent above its pre-pandemic level. GDP was up close to 10 per cent for the previous 12 months.

Australia’s gross domestic product, seasonally adjusted

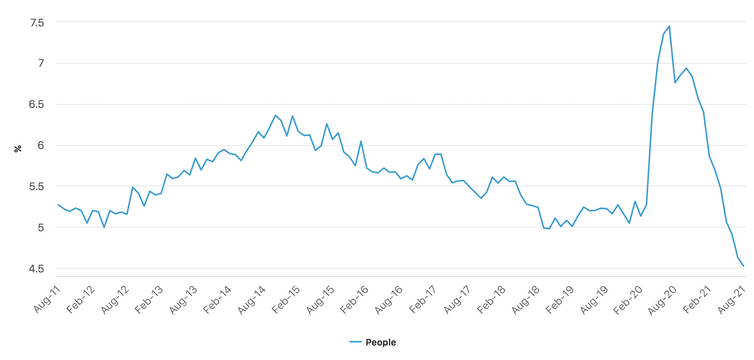

The recovery of the labour market was even more impressive. As Lowe put it: “In June, the employment-to-population ratio reached a record high of 63 per cent and the unemployment rate fell to 4.9 per cent, the lowest it had been in more than a decade.”

The momentum in the labour market was so strong that in July the unemployment rate dropped to 4.6 per cent, despite Delta-related lockdowns in greater Sydney.

Australia’s unemployment rate, seasonally adjusted

Delta thoughts

Lowe went on to discuss the economic hit of Delta.

Of course, how big that hit is depends on vaccination rates and how safely NSW and Victoria reopen. At a time when there’s a fair bit of discussion of best-case scenarios, Lowe warned of grimmer possibilities, warning of the possibility of: “further significant restrictions on activity […] in response to new outbreaks of Delta, the emergence of a new strain of COVID-19 or a decline in the potency of the current vaccines”.

What Lowe hinted at, but didn’t say, was that, absent the Delta outbreak in Australia, the recovery would have continued to drive GDP up and unemployment down. “On the economy,” Lowe said, “our central message is that the Delta outbreak has delayed – but not derailed – the recovery of the Australian economy. If that turns out to be correct then unemployment could fall below 4 per cent by early 2023 – though how far below remains to be seen.

It’s worth remembering that had the federal government not bungled its vaccine buying and roll-out strategy, Australia might have avoided the current economic pain. Finally, Lowe was emphatic the central bank would not be raising interest rates to “cool the property market”: “I want to be clear that this is not on our agenda. While it is true that higher interest rates would, all else equal, see lower housing prices, they would also mean fewer jobs and lower wages growth. This is a poor trade-off in the current circumstances.”

That’s Lowe-speak for: “Read my lips – no interest rate hikes until 2024.”

OECD’s report card

The hefty OECD report (about 130 pages) concurs with Lowe’s view on strength of Australia’s pandemic recovery. It essentially congratulates the government for its response, noting “fiscal policy has responded with unprecedented force”.

But it also notes the low rate of Australia’s goods and services tax (GST) compared to consumption taxes in other countries, leaving the federal government (and thereby state and territory governments) reliant on personal income taxes. The report observes that GST revenue as a share of total taxation has been falling – from 15.4 per cent in 2003-04 to 14.1 per cent in 2020-21. It suggests increasing the rate of GST would lead to a more efficient tax mix.

This puts both side of politics squarely on notice that serious tax reform needs to be on the agenda soon. The OECD report also emphasises the importance of the Australian economy de-carbonising more rapidly. This is another big policy reform on which the government has show little inclination to take stronger steps.

Common threads

So the RBA and OECD both point to Australia’s strong pandemic recovery, driven in large part by the fiscal force of programs such as JobKeeper and JobSeeker.

The Delta outbreaks have put a serious dent in this recovery. But there is reason to believe the recovery will be back on track by early 2022. In the longer term, though, there will have to be a reckoning about major structural reforms. By 2050 we will need to have a largely de-carbonised economy. We are also going to need to have an improved tax mix to drive innovation. And sooner rather than later the housing affordability crisis must be addressed.

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub @UNSWBusiness, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative, and President-elect of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. His research expertise includes contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.