Taking China to the WTO plants a seed, but it is no 'quick fix'

Although Australia's best bet is taking China to the World Trade Organisation to resolve escalating trade disputes, it won't be an easy win, writes UNSW Law's Dr Weihuan Zhou

Australia is reportedly ready to initiate its first litigation against China at the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

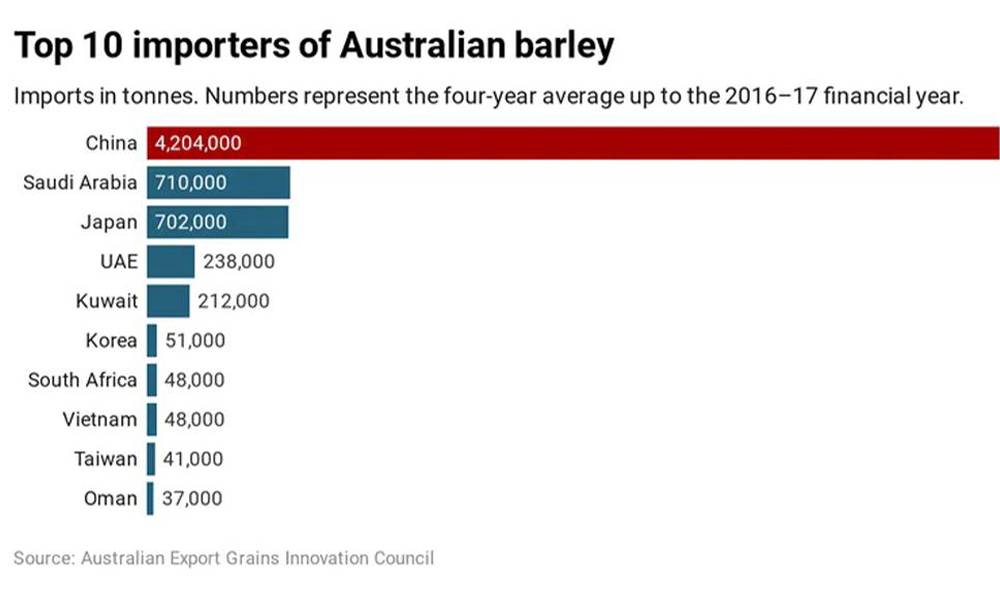

China has this year taken punitive action against imports of Australian coal, wine, beef, lobster and barley. It is the five-year 80.5 per cent barley tariff China imposed in May that Australia will take to the WTO. More than half of all Australian barley exports in 2019 were sold to China, worth about A$600 million a year to Australian farmers.

Chinese authorities began an anti-dumping investigation into Australian barley in November 2018. Anti-dumping trade rules are meant to protect local producers from unfair competition from “dumped” imported goods.

Dumping occurs where a firm sells goods in an overseas market at a price lower than the normal value of the goods. China calculated the normal value of barley using “best information available” on the grounds that Australian producers and exporters failed to provide all information Chinese investigators requested.

The barley tariff will last for five years unless Chinese investigators initiate a review and decide to extend it beyond 2025.

What can Australia hope to achieve from a WTO dispute? Not a quick and easy win. A formal resolution will likely take years. But it plants a seed, starting a structured process for dialogue. This is an important step in the right direction.

A lengthy process

WTO litigation is no quick fix. There is a set process that moves through three phases – consultation, adjudication and compliance. The standard timetable would ideally have disputes move through consultation and adjudication within a year. In reality, it often takes several years, particularly if appeals or compliance actions are involved.

The timetable schedules 60 days for the first stage of negotiations, though these can take many more months. That’s worthwhile if it leads to a resolution. But given the tensions between China and Australia, a quick resolution looks remote. The adjudication process typically involves a decision by a WTO panel followed by an appeal to the organisation’s Appellate Body.

A WTO panel is meant to issue its decision within nine months of its establishment, but it usually takes much more time. If the panel’s decision is appealed, the Appellate Body is meant to make its decisions within 90 days, but nor is this time frame met in many cases.

Once a WTO decision is final, it is up to the losing party to comply with the ruling. That may include a request for time to make the necessary changes. In practice, this can take six to 15 months.

Appeals blockage

One complication is the current non-functioning WTO appeals process. Appointing judges to the WTO’s Appellate Body requires agreement from all WTO member nations. US obstruction of new appointments has reduced the number of judges to zero, and the Appellate Body requires three judges to hear appeals.

This paralysis has created a major loophole, enabling an “appeal into the void” to block unfavourable rulings. In light of this, the 27 European Union nations and 22 other WTO members – including both China and Australia – have signed on to a temporary appeals process known as the “multi-party interim appeal arbitration arrangement” (MPIA).

Given China’s commitment to the WTO and its dispute settlement system, there is no reason to anticipate it snubbing interim arrangements if an appeal arises. But the appeal process is also likely to take just as long as the Appellate Body procedure.

No guaranteed win

Federal Trade Minister Simon Birmingham has expressed confidence in Australia’s “strong case” but victory against China is not assured.

China’s tariff on Australian barley comprises an “anti-dumping duty” of 73.6 per cent and a “countervailing duty” of 6.9 per cent. Anti-dumping and countervailing calculations are highly technical. Whether China’s barley tariff has violated WTO rules will require a detailed examination of its methodology.

A key challenge to the Chinese methodology is that it largely disregarded information on domestic sales by Australian barley producers and used data from Australian sales to Egypt. The WTO has found China’s use of similar methods in several past disputes breached WTO rules. But every case depends on very specific facts. The past rulings against China do not necessarily predict the result here.

No compensation

Even if Australia is successful, a “win” isn’t total. The WTO system is designed to make states change their ways. It is not designed to compensate those harmed by illegal trade measures. In other words, an Australian win may require China only to remove the tariff, not compensate those who paid more or lost revenue as a result.

There is also a risk that China could simply initiate a re-investigation of the barley tariff, which might lead to a decision to impose duties very similar to the original ones. In some past disputes, it took China five years or longer to remove duties.

So even if the World Trade Organisation rules in favour of Australia, this might not lead to the tariff’s end before its current expiry date in 2025.

Still the best option

Despite all this, the WTO is Australia’s best step. The WTO is not perfect, but it is now a tested and respected mechanism to resolve trade disputes.

WTO litigation also compels the disputing parties to enter into consultations – and talking is something Australia’s officials have had difficulty having with their Chinese counterparts.

China might drag its heels in other ways, but it can be expected to respect the WTO’s procedural rules and enter into these negotiations. Those talks could help repair communication channels better than missives through social media and press conferences.

Litigation the new normal

In commencing a formal dispute, Australia also sends a firm but dignified message – that it is willing to use international rules and procedures to solve grievances.

WTO litigation is a normal feature of trade relations between countries. Even close allies bring disputes against one another – such as New Zealand’s case against Australia’s restrictions on New Zealand apples, or Australia’s case against Canadian restrictions on imported wines in liquor stores.

China and Australia badly need a relationship reset. Meeting in a rules-based forum with structured processes for dialogue can do no harm.

Dr Weihuan Zhou is a Senior Lecturer and a member of the Herbert Smith Freehills China International Business and Economic Law (CIBEL) Centre at UNSW Law. This article first appeared on The Conversation.